Andy Cohen and the Gay Male Gaze

His favorite question to ask on WWHL is a bit of a head-scratcher.

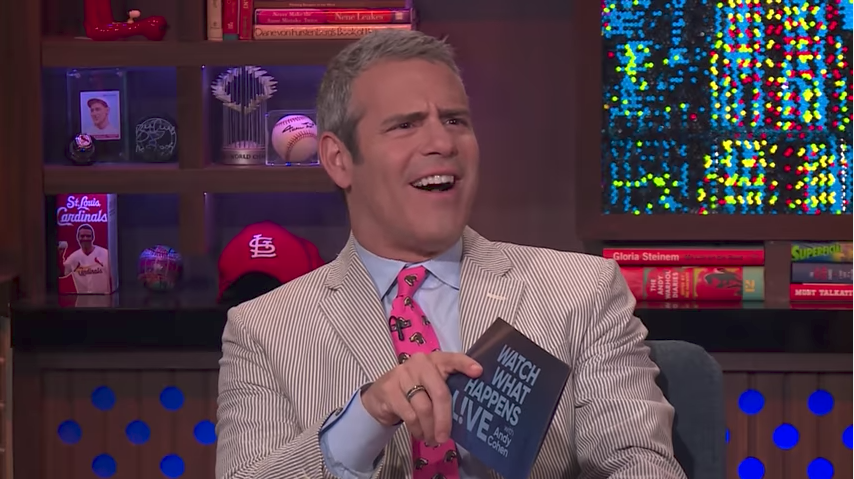

On his Bravo talk show “Watch What Happens Live,” Andy Cohen asks essentially every female guest whether they’ve ever “taken a dip in the lady pond” — engaged in homosexual behavior. As a queer woman — and, well, just a woman — I’ve been troubled by this practice for a while. Ilana Glazer’s overt eye roll when asked the fated question last month felt refreshing but also long overdue.

After Ilana says that she’s been in the “deep end” (bless her), Cohen follows up by asking her where she went to college — he pictures her “experimenting” at a place like Vassar or Sarah Lawrence with a hearty laugh. With no evidence at all, Cohen’s mind immediately jumps to what he would consider a “non-serious” encounter, completely misreading Ilana’s answer of being in the “deep end” as a signal that her experience with a woman was serious, literally “deep.”

In interrogating women about their homosexual histories as a gameshow joke, Cohen cheapens female sexuality and perpetuates the stereotype that women sleep other women as a trendy experiment rather than a legitimate sexual preference. Bravo’s own website also expresses this sentiment, writing that it’s “one of Andy Cohen’s favorite questions to ask his female guests” and that “[the] answers are frequently exciting — with no shortage of both Bravolebs and celebrities admitting to partaking in a little girl-on-girl action.” Cohen does not ask an equivalent question of the men on his show.

The dual forces of misogyny and homophobia make the experience of coming out as a queer woman particularly anxiety producing, and Cohen’s television antics both exemplify and contribute to this anxiety. When he plays into the “excitement” involved in women-on-women action before television audiences, he caters to a patriarchal culture that encourages homosexual behavior between women as nothing more than a titillating object of male desire. Dazed recently wrote in regards to pornography that the appropriation of queerness is “far from revolutionary,” but is rather the “by-product of a voyeuristic gaze that values men’s arousal above all else.”

In Mike Mills’ recent film 20th Century Women, 15-year-old Julie (played by Elle Fanning) is asked by a guy friend about the female orgasm. “I don’t have them,” she says following a short pause. “None of my friends do.” The boy is shocked. “What?” he asks. “Then why do you do it?” Heartbreakingly, she responds: “The way they look at me.”

In coining the term “male gaze” in the 1980’s, film scholar Laura Mulvey argued that men are socialized to stare at women as objects in order to control them. While not sexually/romantically interested in women, gay men are not immune from the corrosive influences of the patriarchy. Yet because misogyny is thought to be intrinsically linked to sexual desire and gay men tend not to present the same threat to women’s bodies (i.e. rape, sexual assault), they are often granted a societal pass.

Andy Cohen is able to get away with invasive and explicit questioning which, if it came from a straight man, would undoubtedly be viewed as harassment. For example, in 2015, he asked Nicki Minaj: “Who has the biggest dick in the music industry?” Minaj politely responded that she did not know because she had been in a 10-year relationship. Afterwards, he asked to take a selfie with her butt, which she declined.

When Advocate writer Eliel Cruz asked female readers in 2015 about misogyny they had encountered from gay men, he was inundated with responses that detailed gay male fat-shaming, slut-shaming, touching women without their consent, and giving critical and unsolicited beauty advice. These responses, Cruz wrote, provided “a clear example of gay and bi men asserting authority over women by critiquing their appearance.” And Bravo — which turns women into spectacles to be alternatively praised for their appearances or teased for their “exciting” antics (such as partaking in “girl-on-girl action”) is a prime example.

On one episode of “Sex and the City,” Samantha says: “Gay men understand what’s important — clothes, compliments, and cocks.” Like “The Real Housewives,” “Sex and the City” depicted stories surrounding powerful career women through the controlling arm of a gay man. Creator Darren Star said that although none of his shows were explicitly gay shows, they were about the gay experience (he knew that if he wrote and casted women as opposed to gay men, his shows would have a wider appeal). Accordingly, the New Republic deemed “Sex and the City” an “ingenious affirmation of a certain type of gay male sexuality,” a point hammered home on the “The Simpsons” when Marge calls it “the show about four women acting like gay guys.”

Women’s Studies professor Ailbhe Smyth takes issue with the fact that media-savvy gay men provide a “very camped-up view of stereotypes of femininity.” Smyth expressed concern over these gay male generated female stereotypes because gay men “have all the power in US television,” and “US television is dictating how we all look at the world.”

Cohen himself recently admitted to New York Times Magazine that his relationship with the women of “The Real Housewives,” which Cohen is credited with creating, is problematic to say the least. He painted a portrait of himself as the stable father-figure to an army of explosive women in desperate need of his controlling hand:

A lot of them view me as kind of their daddy in some weird, sick way, and their boss, and their friend, and their boyfriend, and their enemy — and so there’s a lot of different psychological layers happening in a situation like this[.] Some of them are volatile women. So it’s all real. It’s all real.

Demonstrating Cohen’s influence, when rumors surfaced on Season 9 of “The Real Housewives of Atlanta” that certain cast members had engaged in lesbian behavior, the housewives assumed Cohen’s idiolect, speculating about whether certain women had “dipped in the lady pond.”

And these examples extend far beyond the Bravo-universe. When Cara Delevingne’s first homosexual relationship (with Michelle Rodriguez) became public in 2014, the young model was adamant that she was not gay but rather was just “having fun” — she used the phrase “having a good time” twice her short statement to the Telegraph. Around the same time, when I had my first girlfriend, I was similarly insistent that I was not a lesbian. Rather, I wanted to embrace the representation that I saw in the media — the one where I could “experiment” without committing to a sexual identity, where could act on my feelings and avoid coming out, where I would instead be praised for my “wild antics.”

I at first viewed this as a type of privilege: women are given the space to be sexually fluid in the ways men are not. But once I had my first girlfriend, I realized this space is narrowly prescribed. Much like Andy’s reaction to Ilana’s “deep end” comment above, my world had trouble understanding that I wanted to romantically partner — not just “have fun” — with another woman.

Bravo’s cultural impact is nuanced and complex. (In some ways, Bravo is radically feminist in that it portrays a world in which powerful women’s stories reign supreme.) I cannot possibly blame Andy Cohen for the fact that over ten years passed between the time I first kissed a girl to when I had my first girlfriend. However, the widespread cultural message that “fun” women can hook up with other women for a “wild time” discouraged me from embracing a queer label, and made it more difficult for me when I finally did. I know I’m not the only one in this position. Given his immense cultural power, Cohen should think twice about how his “favorite question” contributes to a long and painful narrative of men exercising control over female sexuality.

Anna Dorn is a writer and attorney living in Los Angeles.