The 1830s Are Back Like A Statement Sleeve

Is Romantic nationalism back too?

We are demonstrating, we are protesting, we resent the decisions of our parents’ generation, we are broke, the White House is occupied by a catastrophically destructive populist weirdo, we are being compelled to wear increasingly bizarre sleeves. It’s happening. Finally. The 1830s are back.

Now is the time of the “statement sleeve” aka the weird sleeve, from cold shoulder to balloon, to fluted, to “sculptural,” to ???, to the ones that end with little ties instead of cuffs, to just an extra $1,000 sleeve, to any combination of these features. I have recently had and overheard multiple conversations about sleeves, conversations not had during the Obama administration. It’s a moment, one which coincides with a participatory form of civil unrest from which primordial soup have emerged a nonzero number of soul-crushing takes about how protesting is the new brunch.

The last time this happened was 1830, when women* in Western Europe wore the largest sleeves of any period in sleeved Western European history. Some of the stuff I’ve gotten Lyst alerts about in this week alone would give that fact a run for its money.

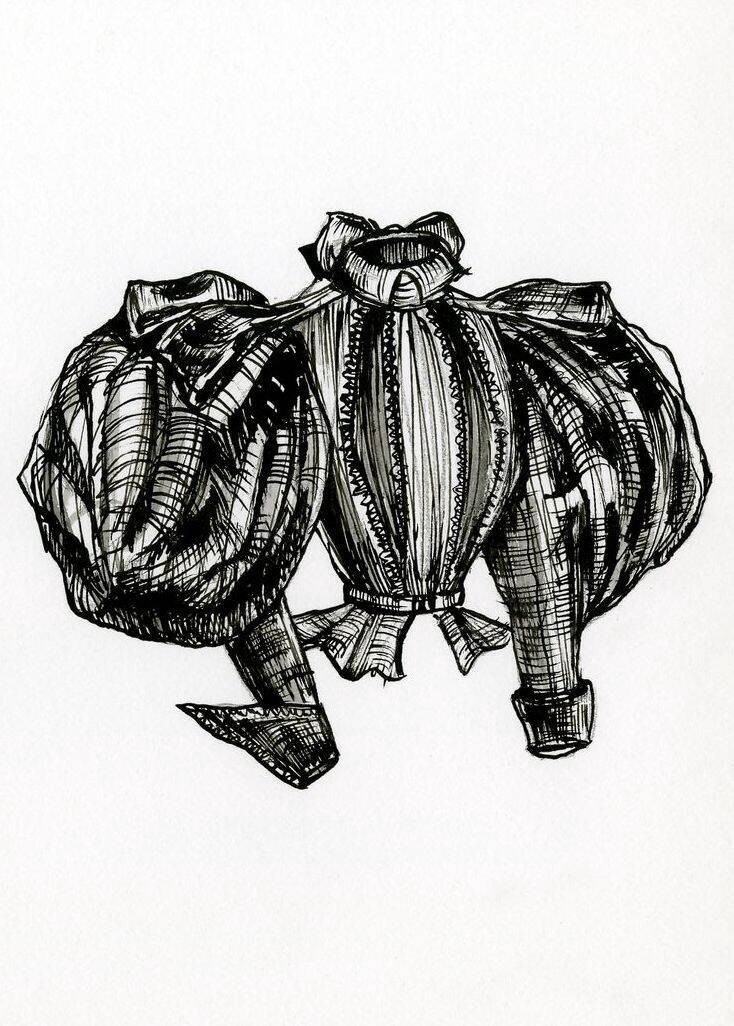

Then, as now, sleeves erupted from the small, innocent sleeve of the Empire gown to the leg-of-mutton and elephant sleeves, a dropped shoulder silhouette that poofed so dramatically from the bicep it was enforced with whalebone, then narrowed at the forearm or wrist. Like a leg of mutton. Like an elephant’s ear. Like an inverted teardrop. Like nearly every goddamned sleeve in 2017.

Unlike previous generations of wacky sleeves like the virago, finestrella, and paned sleeve, these did not reveal an undergarment, which suits both modern sleeve construction and possibly modern undergarments. And unlike the sleeves of the Victorians, but like the sleeves of today, the poof began below the shoulder. In our case, it is most often dropped below a bare shoulder, prompting me to constantly ask everyone I’ve ever met what kind of bra you’re supposed to wear. In the 1830s this bare shoulder was most often covered, in daytime, by a little shoulder cape called a pelerine so nobody had to struggle with those goo bras or removable straps. Advances in printing and a taste for the naturalistic over the classical meant that preferred patterns were floral or striped.

What else was going on in the places where people may have worn these sleeves or seen a great deal of them? In France, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, Poland, Brazil and Portugal, revolutions were going on! In the U.S., under the presidency of populist Andrew Jackson, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, one of the most gruesome and morally outrageous pieces of legislation concocted in human history. As the 1830s wore on, coal miners in Wales revolted, Gran Colombia dissolved, Germans gathered for the Hambacher Festival in a pro-republican demonstration that was also apparently fun. Ada Lovelace met Charles Babbage, so that one day we might be able to tweet poo emojis at reporters.

Nationalist uprisings took place at the edges of the Ottoman Empire, specifically Greece and Bosnia. Across Algeria, nationalists revolted against the French occupancy that recently replaced the Ottoman. In Canada, Ottawa and Quebec revolted. In Brazil, Rio Grande do Sul attempted secession. In the U.S., so did Texas. When the 1830s were semi-wistfully remembered by Victor Hugo, they were embodied by Millennial patron saint Marius Pontmercy, a mortifyingly awkward law student who couldn’t pay rent but ate desert every night and joined the antimonarchist revolt mainly out of FOMO. The end of the East India Trading Company’s monopoly on trade from China meant that then, as now, actual opiates were the opium of the masses.

This is not to say that I have recently attended a post-Napoleonic nationalist uprising or that I think a politically empowered middle class is a new thing. But history has endlessly proven its ability to look superficially familiar and here we are, wearing these sleeves, Q.E.D.

So why sleeves? They’re expressive, gestural, and silhouette-changing. They have throughout the course of human events variously indicated rank, wealth, and Cavalier-Roundhead affiliation. They have flashed our undergarments, covered our unbearably sexy arms, tactically revealed our unbearably sexy arms, served as pockets, and concealed or revealed our hands according to taste, culture, and fashion.

The dropped shoulder of the 1830s represented a Romantic ideal, as did fancy hairstyles and fabrics. Fashionable people of that era recalled the Empire and Regency costume of narrow, gauzy dresses and overt Classical references with horror; Romanticism was at once more modest and more liberated. Now, as then, none of the shapes being played with are new, but rather reimagined references in new prints, proportions, and details. They express traits like creativity and boldness, and since they do not exist in menswear, imply some celebration of the variety allowed in modern female dress, even at the price of bra confusion and that godawful red mark you get from carrying your bag around all day. “While speaking to current tastes, these sleeves are also classically romantic and appeal to feminine women of all ages,” wrote a WWD observer, while earlier referencing their ability to evoke “retro Sixties and Seventies aesthetics.”

Why did they grow so quickly? Maybe everyone’s arms were getting super ripped from carrying around carbines (then) and knitting pink hats (now) all the time, and narrow sleeves would be inconvenient. But, as anyone who has worn a cold shoulder poofy sleeve top on the subway with a tote bag can tell you, this is the opposite of practical. People were, and are, ostensibly doing more stuff, so why not really sturdy sleeves that can support civic action? Probably because fashion reflects our aesthetic instinct more than it literally describes what we’re doing on a day-to-day basis, and this is a shakeup. Sculptural silhouettes represent a desire to move into the future, retro details a yearning for the past. By 2018, “to sell a basic shirt [sleeve] will be out of the question,” said trend forecaster Li Edelkoort. Out of the question!

We’re just so overwhelmed that we have to wear it (with) our sleeves. Whether the overwhelming feeling is Romantic nationalism, #resistance, solidarity, wistfulness, optimism or despair, there is too much of it to face in something as utilitarian as a narrow sleeve. If we are shouldering some kind of burden, we are doing so on our bare shoulders (or bra strap-covered shoulders? Please send help.) The 1830s are back. And since some stuff I saw at Zara clearly indicates we’ve plunged into a time warp where we’re given a do-over, our lessons are clear: Do not allow a cruel populist president to continue humiliating us in front of the other eras, don’t kill whales to reinforce our giant sleeves, don’t grow up to be the conservative reactionaries of 1848, and lay off the opiates.

*What were men wearing? Suits. Hats. Next question.

Rebecca Christopher is a writer with access to several Zara storefronts and the works of Balzac.