On The Brandwagon

Benebabes, Tartelettes and the rise of the cult makeup follower.

The first beauty brand I started religiously following on social media was Maybelline. As someone who uses incredibly few drugstore makeup products, it was definitely out of character. But this beauty blogger I enjoyed had been plugging Maybelline’s social accounts for a bit, and I am weak when it comes to learning about products that I’ll probably never purchase but can watch other people effortlessly glide onto their Snapchat-filtered faces.

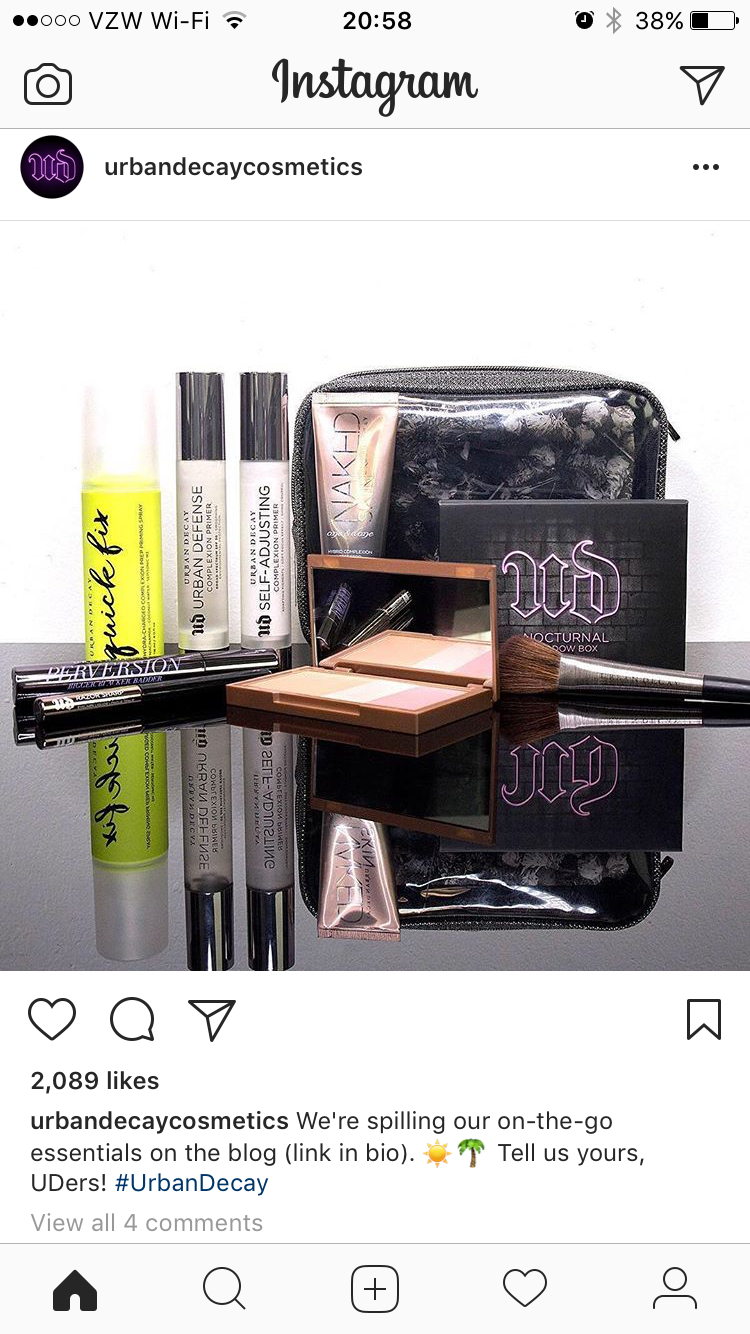

Overnight, Maybelline’s Snapchat story became a normal part of my social media diet. Later I added Tarte, Smashbox and Benefit to the mix. On Instagram, where brands are far more active, I flooded my feed with all the above, but also Laura Mercier, Urban Decay, Morphe Brushes — literally any brand that could game the algorithm enough so my feed would be filled with makeup tutorials to copy and products to put into my cart got a instant follow. But as any new obsession begins with frenzied endorphin high of discovering Holy Shit There Are People Who Love This Stuff Too, every new obsession also comes with the startling realization of Can I Really Keep Going With This Nonsense? Sometimes it’s the fan fiction you find yourself clicking on at 2 A.M. that’s just too ridiculous to be creatively respectable, or maybe it’s when your bank account balance cannot be reconciled with the full-price matinee tickets that you really want.

This time around, though, the Nonsense in question was the patently absurd names makeup brands gave to their fans and followers. Really, these are the names makeup brands give to their family. Because they want to convince us that we’re family and their brand is the brand that truly cares. Maybe their social and marketing teams really do care, but when it comes down to it, these are the names they’re giving to their consumers to entice them to buy their products. Despite the niceness of the Makeup Internet, it’s still capitalism and your dollars are still the goal.

I started realizing the trend of weird names slowly, of course. Every morning, I would check my snap stories and there, under the Maybelline Snapchat handle, would be a curly haired brunette saying “Hey Babellines!” (Eventually I would see it written out on Instagram so I know there’s no hyphen.) It was easy to dismiss one name. But the deeper I went into makeup social media, I realized it wasn’t just one brand or one dumb name. It seems that most of the makeup industry is relying on these names to create a family and take those family dollars when makeup consumption may soon no longer be defined by haul size alone.

How did all of these companies seem to follow the same culty belief that all followers need a name so quickly? Babellines was obviously the first one I realized. But after a well-loved sample of Benefit Cosmetics The POREfessional Face Primer, I found the colony of the Benebabes. Influencers/YouTubers are called Friends with Benefit, you know, as not to confuse us normies. Benebabes (or its corollary) didn’t roll off the tongue quite as easily with all those pesky b’s, but I was willing to overlook it.

Until I realized the marketing fad of naming your customers had invaded brands from the highest end cosmetics to the cheapest CVS aisle. There’s Rimmel Rebels, Lorealistas, Tartelettes, Morphe Babe, the (not well thought out) UDers for Urban Decay, and BECCA Beauties for Becca Cosmetics. Then there’s also Nars’ NARSissist, Jouer Girl and the members of the Smashbox Squad. Surely the high-brow department store makeup brands owned by the same conglomerates that produce these drug stores and mid-level market brands wouldn’t succumb to such lame marketing. You would think so. Yet, there’s still Estee Beauties for Estee Lauder and Mercier Muses for Laura Mercier.

It feels misplaced to be so irked by these sorts of names because fandom names (which is what these are trying to be) have existed since before the internet. Trekkies comes to mind immediately. If you were on the internet at all last year, the frenzy of Hamiltrash (the fandom name for the musical Hamilton) reached its breaking point around the 2016 Tonys. If you log onto Tumblr, you’re find a fandom for whatever you want. I promise. But all of these names are self-imposed. If they’re used to appeal to viewers or consumers, it’s because the company noticed the crowd gathering around the name after the fact. The company wasn’t responsible for creating it; the best ones come from organic growth. But in an age where you’re trying to quickly bring your makeup to market, there isn’t always time for organic growth.

Yet, while it’s weird to watch as these modern makeup brands scramble over one another to grab the next trendy name, they aren’t the first makeup brand to use an odd name to try to build a community around their products. These brands are just not quite as good at it. In her book, Enterprising Women: 250 Years of American Business, Virginia G. Drachman describes the reign of Elizabeth Arden and her “Arden girls” that took over high-end department store counters in the early 20th century. “The meticulously groomed Arden girl, ‘trained to a perfection of smart hauteur,’ deliberately exuded an aura of glamour,” Drachman writes.

This sales force was an expensive but worthwhile investment. Annual salaries and expenses ranged from five thousand to eight thousands dollars, but a weeklong visit by an Arden girl to the Elizabeth Arden counter at a department story could earn that store up to six weeks’ worth of sales.

In cultivating the haute customer with an aura of mystique, Arden made a profitable business despite her fierce competitors from equally successful women like Helena Rubinstein. (There’s even a musical about these two’s competition for the American woman’s face.) Arden’s business, according to Drachman’s book, was grossing $2 million a year by 1925 and she increased that to $8 million by 1929. Arden sold the color pink and possibility of eternal youth through her bottles via her Arden girls. Building a named fandom around her products made her one of the most famous and profitable makeup moguls of the 20th century. But Elizabeth Arden had much fewer competitors back then than the Laura Merciers and Maybellines of the world do today.

Every time I open Instagram, I see another brand has jumped on the bandwagon. What started as a way to shut off the unpredictability of every day in America has turned into another obsession, and I’m now a collector of dumb names that brands have given their consumers. The attempts to build an artificial community around this specific consumer good stand out like a clown at a funeral. Because while makeup lovers are buying palettes, foundations and liquid lippies, is anyone actually calling themselves a Tartelette? A Jouergirl? A Lorealista? A BECCABeauty?

An Arden girl was aspirational after all. But in an age where No-Makeup Makeup reigns, what is a Benebabe beyond a marketing ploy that’s hard to say?

Caitlin Cruz is a freelance reporter in Brooklyn and Dallas. Tell her about your red lipstick: [email protected]