How Women Learned To Love Chocolate

The marketing of indulgence.

As a kid, every year I’d trek to the mall to buy my mother peppermint foot cream for Mother’s Day. “Great,” she’d say as she unwrapped it, then stashed it in the closet next to her collection of unopened peppermint foot cream bottles. “Just what I wanted.” After a while, it became clear that what she really wanted was chocolate. Especially now that I’ve devoted my life to writing about the stuff, she wants to reap the rewards. And so every year, I send her a few choice chocolate bars for Mother’s Day.

Something about this request has always made sense, the way the nursery rhyme “sugar and spice and everything nice” has always existed. Except, well, it hasn’t. It was written in the 1800s. As cultural norms around both women and sugar changed at the end of that century, savvy marketers intentionally associated chocolate and sweetness with women so strongly that we now see the bond as a fundamental truth.

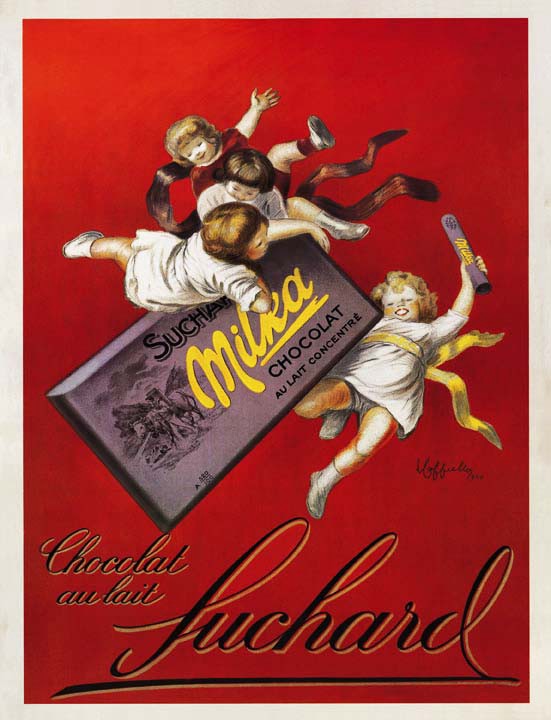

The first chocolate advertisements didn’t have anything to do with women. Instead cherubs, angels, and children fluttered around chocolate bars and bonbons. Sugar — and, by extension, chocolate — was a luxury, an expensive treat for the lucky few who could afford it.

In the late 1800s, technological advances made it much easier and cheaper to produce sugar. The price dropped, and suddenly everyone had access to it — including women. In 1874 The New York Times announced that young women from monied families were the “class of persons that, more than any other, purchase or have purchased for them, the most elaborate style of French candies.” And a male New Yorker wrote to his British family members in 1876 that women’s candy consumption was “enormous” and a “great national failing.”

Sweetness, which people had mainly used to describe the scent of flowers, found itself front and center, and all the femininity ascribed to flowers transferred to other sweet things, like chocolate and candy. It made perfect sense that something so inessential and trivial would appeal to women, who were, after all, somewhat inessential and trivial themselves. Scholars will tell you it’s no coincidence that sugar’s economic devaluation coincided with its association with women and femininity.

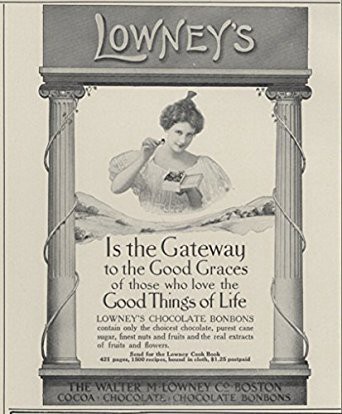

In 1895 Lowney Chocolate, in the U.K., paired women and chocolate in new way, with five pornographic advertisements featuring women.

Doesn’t look obscene to you? Not lewd enough for a twenty-first-century stare? Let’s just say the Victorians had different standards: A woman publicly displaying her desire (even for chocolate!) read as blatantly sexual. Just look at the lust in her face! And her bare neckline— oh my. Lowney set the standard for advertising and its lovely male gaze for years to come.

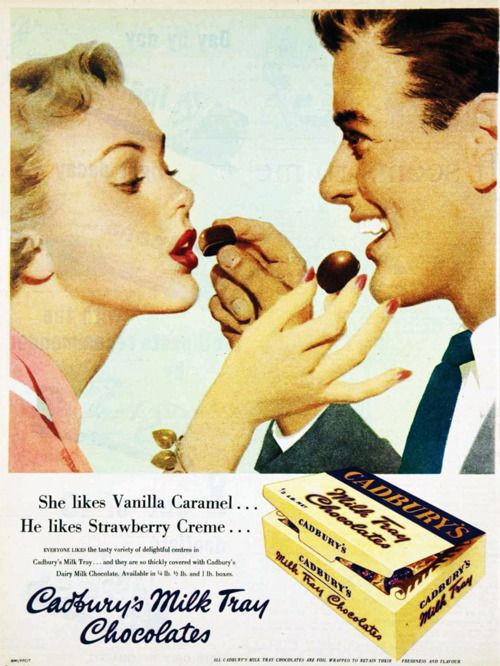

After this point chocolate marketing tended to fall into one of two camps: Bonbons were imbued with romance and marketed to hopeful lovers. (“A Dairy Box of lovely chocs / Will keep your ‘Sweetie’ sweet,” chirped a 1937 Rowntree ad while another promised, “it is possible to have your cake and pat it, after all!”)

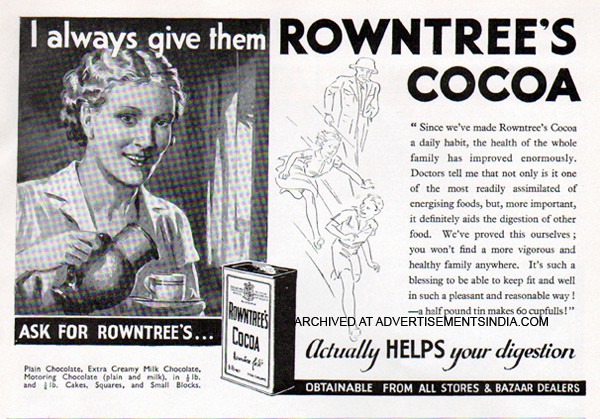

Meanwhile cocoa was marketed to mothers and wives. It wasn’t subtle or unconscious, as this 1951 brief from the J. Walter Thompson advertising firm to Rowntree Chocolate makes clear:

“We are selling to mothers and wives chiefly (because more cocoa is drunk in families with children than in families without, because the woman is the family’s purchasing agent, and because she can be inspired to act in her husband’s and children’s interest when she might not do so in her own). … Any technique by which we can appeal to the mother’s concern for the well-being of her family or her related anxiety about being a successful mother and winning the loyalty and gratitude of her husband and children might serve as a vehicle to make her think of Rowntree’s Cocoa in the way we want her to think of it.”

So Thompson turned out ads like this one, which says, “Since we’ve made Rowntree’s Cocoa a daily habit, the health of the whole family has improved enormously.”

Cocoa was consciously framed as a food to help mothers and wives keep their children and husbands happy and healthy. It’s easy to prepare: Simply mix a couple tablespoons with milk or water, stir, and you have healthy drink to nourish your family. So much easier than cooking — or nursing.

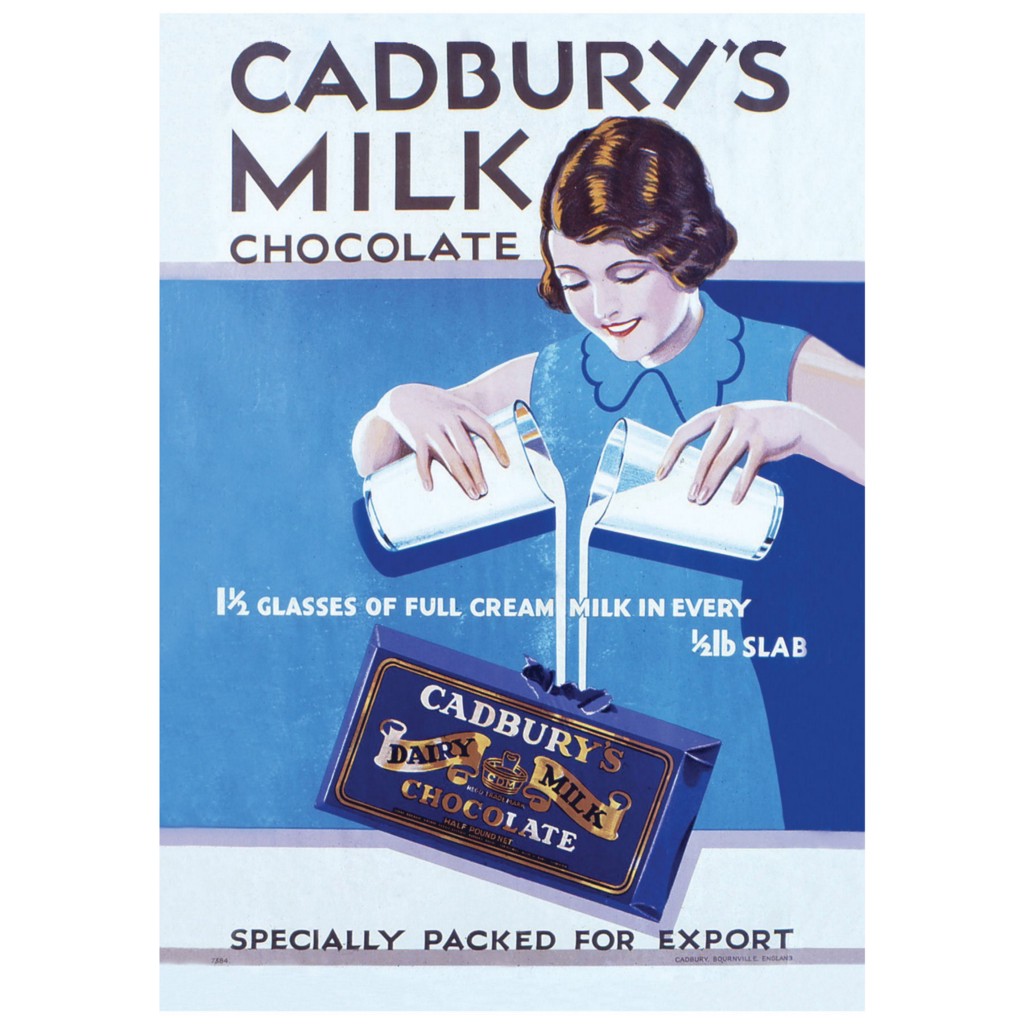

Rowntree wasn’t the only one to get in on the fun. Take this ad from Cadbury from the 1950s: A mother pours two glasses of milk into a Cadbury bar while holding the glasses right in front of her breasts, as if her breast milk is literally being placed into the chocolate.

Mmm, nothing like a glass of chocolate breast milk.

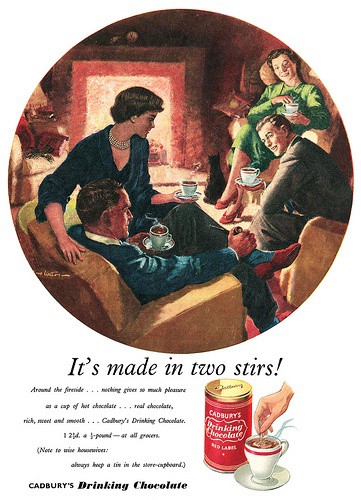

Eventually ads widened their focus to the entire family, promising that housewives could take care of their husbands with a hot cup of cocoa.

So to recap: Men buy chocolate for women as part of the courtship ritual (read: in exchange for sex), and women make hot chocolate for men as a stand-in for breast feeding. Great.

Eventually these two tactics met in the middle. In the early 1960s, men stopped appearing in chocolate advertisements, because the connection between women and chocolate was so intense.

With chocolate, women could take care of themselves (if your mind is in the gutter, you’re in the right place). Hence marketing slogans for Rowntree’s AerO bar like “You say, ‘-ah, that was good’ — and your whole body relaxes in utter satisfaction” and “makes you go O!”

This tradition continues today with countless ads featuring women sighing as they sensuously nibble on a bite-size piece of chocolate with an inspirational (read: cliché) message on the wrapper.

Setting sex aside for a second, the message is still one of comforting ourselves. Take Dove’s newest commercial, which features a girl turning into a woman through the course of a day, enjoying chocolate at each turn, set to Edith Piaf’s “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien.”

It’s been lauded as a feminist ad because the woman is in charge of her own life: There’s no father, no male suitor, just her and her own needs, wants, and desires, which means chocolate, naturally.

Come to think of it, there’s no daughter sending a Mother’s Day present either. Either that means I’m off the hook or it’s time to go shopping for some peppermint foot lotion.