Parenting Philosophy

What did Wittgenstein know about babies?

The world’s most accurate description of what it’s like to have kids does not come from the author of a baby book. Not from benevolent attachment-parenting overlord Dr. William Sears, nor champion of crying-it-out Dr. Marc Weissbluth, nor even the official Blossom of the anti-vaccination movement, Dr. Mayim Bialik* (*not a medical doctor).

Instead, the most — nay, only — appropriate depiction of 3 a.m. at my house comes from none other than Ludwig Wittgenstein, the dead, closeted-gay Austrian father of zero:

Anyone who listens to a child’s cry and understands what he hears will know that it harbors dormant psychic forces, terrible forces, different from anything commonly assumed. Profound rage, pain, and lust for destruction. (Culture and Value, p. 4)

Wittgenstein’s observation is especially striking, given that canonical philosophical study of childrearing is nonexistent. Although I think having a kid certainly qualifies as a ne plus ultra Heideggerian Kehre — a “turn” that reorients one’s entire Weltanschauung, brings an Erzitterung (shaking-up), sets off a Geworfenheit (thrown-ness, in this case primarily of Cheerios) — philosophical investigations of parenting are largely absent from what the field’s practitioners call The Canon.

Why? Well, here’s a wild guess: To the popular consciousness, parenting still means “mothering,” and mothering is the purview of women, who make up approximately 17 percent of the discipline of philosophy’s full-time U.S. professoriate (one that, definitely unrelatedly, also contains 100 percent of academia’s John Searles, Thomas Pogges, Peter Ludlows, and Colin McGinns). Sure, sure, as any philosopher would be happy to remind me (especially the one I live with), correlation does not equal causation. And yet. In a field almost entirely bereft of women (and in which women have long reported feeling threatened and marginalized), a subject that centers on the concerns of women is somehow, for some reason I definitely can’t prove, considered at best irrelevant to, and at worst unworthy of, “serious” philosophical inquiry. (Note: some exceptions exist, but they are not considered “canonical.”)

What mothers get instead is an oeuvre of proscriptive writing called “parenting philosophy,” which, unlike actual philosophy, sells jabillions of dollars worth of books every year, books that deal in an entirely different crop of philosophical topics, and even have their very own “turns.”

The epistemological turn: Your baby knows how to self-soothe.

The cosmological turn: Toddlers are neanderthals!

The ontological turn: Motherhood is the essence of being.

The metaphysical turn: The alleged ‘pain’ of labor is a construct of the pharmaceutical-medical-industrial complex!

And, of course, ethical after ethical after ethical turn: Don’t pick your baby up too much, you’ll spoil him. Never put your baby down, or he’ll develop attachment disorder and end up giving BJs behind the middle-school Dumpster. Don’t ever, ever, ever make a mildly obscene gesture in the general direction of your baby after it’s just taken four hours to put her down for a 22-minute nap.

The latest vogue in parenting philosophy seems to be the “happiness” turn; with three titles in early 2017 alone, Maternal Tranquility Studies seems to be quite the burgeoning subfield.

Take, for example, Breathe, Mama, Breathe (January 3, The Experiment), Shonda Moralis’s pocket-sized primer on how to increase mindfulness and bring to one’s mothering “more presence, more joy, more laughter, more fun, more connection, more compassion, [and] more balance,” and, I am assuming, fewer episodes of Daniel Tiger. I tried several of the book’s suggested “mindful breaks” (my favorite was the semi-pornographic coffee-savoring section: “Is your mouth watering in sweet anticipation?”) And I am happy to report that each mindfulness capsule was, indeed, five minutes in which I was neither making obscene gestures, nor staring at my phone pretending not to notice my daughter trying to eat a nail file.

Then there’s Bailey Gaddis’ Feng Shui Mommy (May 19, New World Library), which is geared toward helping pregnant women align their mind, body and spirit, so as to “best handle the cosmic kick in the uterus and juicy kiss on the soul that pregnancy is.” Sure, why not?

And, finally, there’s Genevieve Shaw Brown’s The Happiest Mommy You Know (January 10, Touchstone), which dares to argue that mothers should treat themselves with the same care and devotion they treat their offspring. Shaw Brown wakes up at dawn to cook her kids all-organic multi-course feasts, dresses them in head-to-toe Ralph Lauren, and takes them to eighty bajillion enrichment activities, so I think what she means is that I, too, should congratulate myself on treating my food, clothes and grooming with exactly the same lovingly-curated attention I treat my daughter’s, i.e. an occasional vegetable and a staunch pro-visible-stain stance.

These “tranquility turn” titles are, of course, the latest in a long tradition of not just telling parents (mothers) what to do to “fix” themselves and their discontented progeny, but how to think about the very act — or identity — of being a parent (MOTHER) altogether.

The ever-churning tide of new titles, and mainstays such as On Becoming Babywise (the Authoritarian Turn), The Happiest Baby on the Block (the Swaddling Turn), or The New Basics (French Deconstructionism) — not to mention the Socrates of Parenting Philosophy, Dr. Benjamin Spock — all exist because they offer mothers a method (or rather, thousands of competing and often diametrically opposed methods) of thinking about motherhood.

I am the ideal target for the world’s glut of parenting philosophies: an older mother, plagued with self-doubt, who likes to read. And I have, indeed, read them all.

None of them work on my kid. I mean, none of them. This is probably because I’ve been “blessed,” as Dr. Sears would say, with a rather high-octane offspring, a constantly moving and perpetually awake little locomotive who has proven herself immune not only to all major eradicable diseases (thanks, vaccination!), but also to any parenting philosophy whatsoever, with the possible exception of Well, Do Whatever You Were Going To Do Anyway, I Guess™.

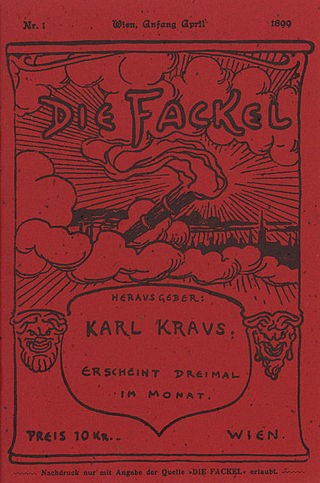

So as an early-career parenting philosopher myself, I can’t help but think, as one does, of dead Austrian flinger of bon mots, legendary grump, and father of zero Karl Kraus, and his ca. 1900 description of psychoanalysis: “It is the sickness for which it believes itself to be the cure.”

I mean, sure, it is possible I have some parenting issues. To use a random example that has never resulted in an obscene gesture: My kid won’t sleep. Like, ever. And if you ask Dr. Marc Weissbluth, he will tell you that by not locking her into her room at 7:30 every evening, I’ve abused her, and possibly set her up for a lifetime of Dumpster-BJs.

And yet: She’s healthy. She’s happy. She just legit isn’t tired until 1 a.m., and that isn’t bad for her so much as it’s inconvenient for me. And you know who agrees with me? La Leche League, who tell me in the book Sweet Sleep that kids often just don’t sleep like adults want them to. Ya burnt, Weissbluth. Except uh-oh, La Leche League also thinks that feeding a kid formula and making her sleep anywhere but clamped onto my bosom = chaining her to the radiator, and I’m reminded of the classic Judy Blume book Blubber, which teaches kids (and adults named me, apparently), that just because the bully is on your side (for now) doesn’t make bullying OK.

So, my own tiredness aside, I think both books are, as Kraus would say, diseases masquerading as the remedy. Because the only thing they and all of the rest manage to accomplish consistently is not encourage my recalcitrant offspring to behave in any way different than was her original, possibly-diabolical plan. It’s that they make me feel fucking terrible.

And this brings me, at last, away from parenting philosophy and back again to actual philosophy, which — despite the exclusion of the parenting experience and somewhat drier nature of the prose — has offered this particular weirdo mother of weirdo child something resembling solace.

When it’s after midnight and all my child wants to do is play the xylophone and watch Planet Earth II like some sort of deranged pothead, it’s not Dr. Sears (or Weissbluth, or Karp) whose words I remember. It’s Nietzsche’s. She who fights with monsters should be careful she doesn’t turn into a monster herself, I mutter as I manage, somehow, to summon the patience to react with calm and compassion, for just another hour (or five). When you stare at the abyss, the abyss stares back, I say to myself, after ten eternities have elapsed and somehow my charge has exhausted into unconsciousness and I feel, once again, as if I’ve spent the evening whispering soothing platitudes into the mouth of Hell.

When my daughter spends the better part of an afternoon trying to reach the giant serrated knife we’ve placed out of reach on the counter, until the various acts of trying-to-reach themselves become the activity of choice, I think not of the Toddlerwise toddler management system — a.k.a how I should be employing corporal punishment to dissuade her from further acts of disobedience — but rather, I think of how this fits in with the quintillion other Hegelian dialectics we’ve engaged in on any given day.

And, on the extremely rare occasions that my progeny does something “correctly,” like take a nap in her own bed at noon for two hours, and then go to bed without incident at 9 p.m., instead of proclaiming that whatever “training” I have attempted has “worked,” I simply remind myself what Wittgenstein said about following a rule. (Spoiler alert: He said: “No course of action could be determined by a rule, because every course of action can be made out to accord with the rule,” Philosophical Investigations §201.)

Much unlike the parenting philosophy that does nothing but make me feel like a profoundly worse mother, the actual philosophy manages to de-isolate me, to situate my profound parenting mishaps in the larger scope of the pained, profound trajectory of human experience.

And yet. I’m not fixing to cure the disease of prescriptive parenting by worsening it. Just because something happened to keep me — a specific person with a specific situation and a specific child — from the knife edge in a specific instance doesn’t mean I think anyone else should go looking to Johann Gottlieb Fichte for good ideas about teething. Wittgenstein, after all, spent the entirety of the Tractatus logico-philosophicus (a philosophical treatise, or so we’re led to think) proving that philosophical treatises make no sense — including his own. Parenting philosophy is the same, including anything I’ve said here.

That of which I cannot speak, I must cry over silently while my toddler has a fit in the middle of Walgreens.