Live Victorian Nudes!

The rich cultural history of tableaux vivants.

I always think I am bored by the Victorians, and then I remember tableaux vivants — people (mostly women) in costumes, holding poses for an audience of their friends, and I wonder at history anew. Tableaux are so essentially Victorian, but they also undermine the supposed rigidity of the Victorian period that the moderns and the flappers later liked to define themselves against.

In the nineteenth century in Britain and the United States, tableaux vivants (“living pictures”) were the wildly popular form of pageantry and theatre wherein all sorts of folks dressed up as figures from art and literature — and by “dress up,” I mean mostly undress — on the stage or at house parties. In James H. Head’s Home Pastimes: or tableaux vivants, published in the U.S. in 1860, he writes loftily, “Art should not be confined entirely to the studio of the artist. Her presence should embellish every home; her spirit should animate every mind.” Tableaux were supposed to allow mass access to high culture; therefore, middle-class young women, usually the most policed for propriety, could make a claim to virtue while also performing seduction.

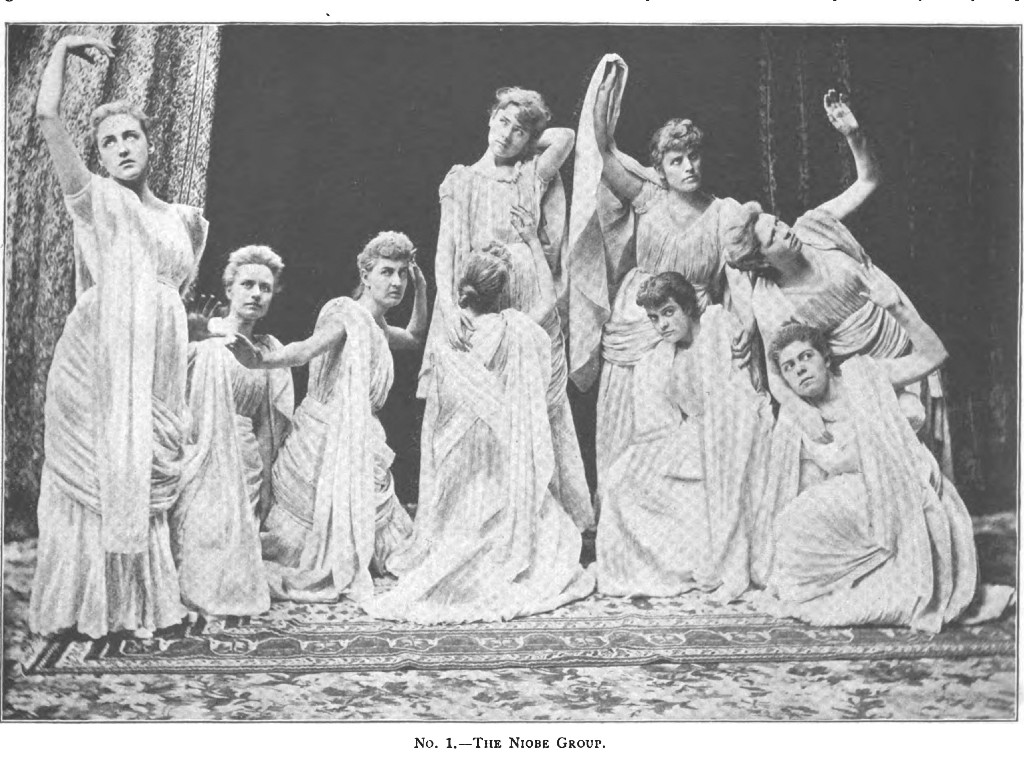

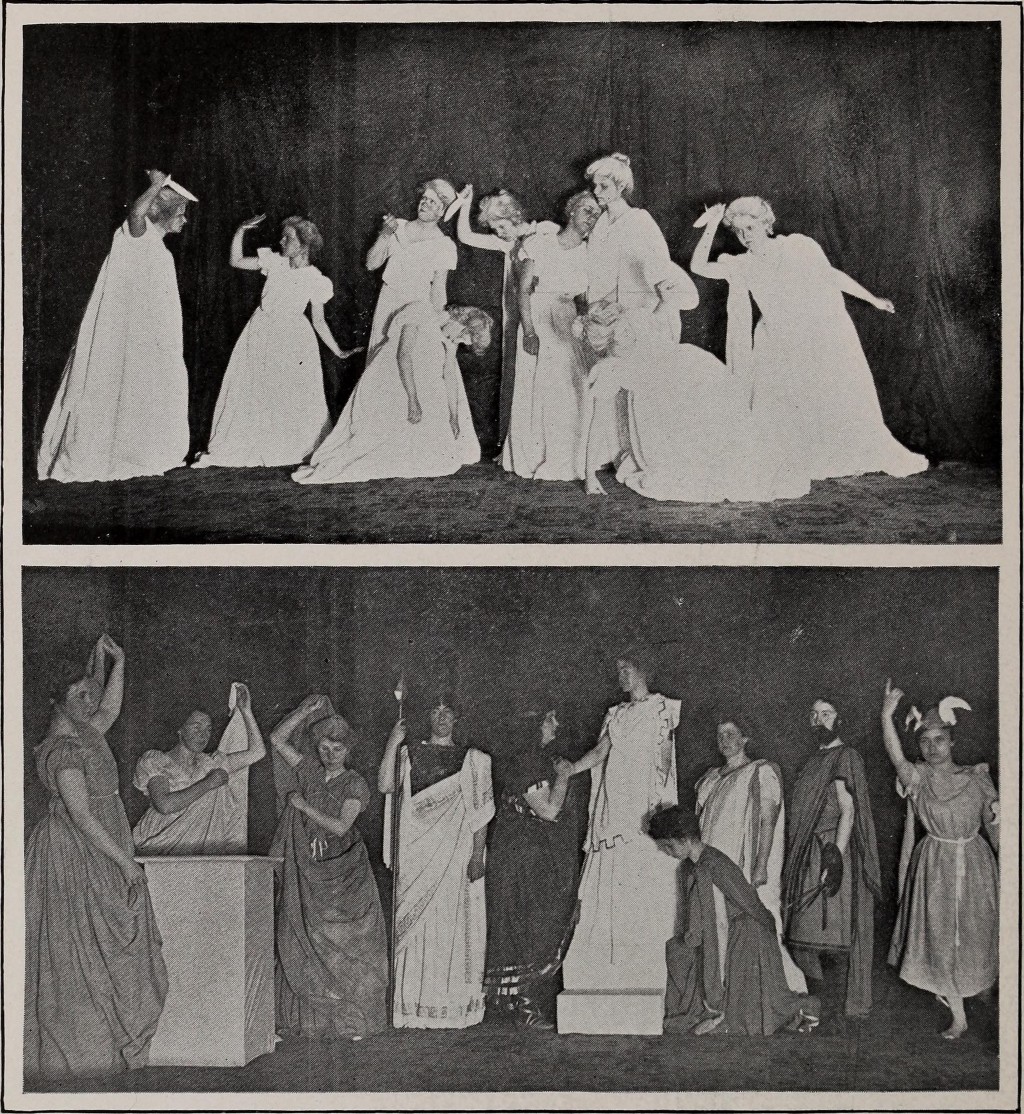

In the parlor game version of tableaux vivants, people would rustle up various household objects and old clothes to serve as togas and other costumes or props. They would create a temporary stage and curtain, and then arrange themselves under the direction of someone with artistic vision (the Amy March of the group), into a frozen melodrama or frieze. When the curtain was flung aside, the audience would get a half minute to stare, and sometimes guess, charades-like, at what was being represented. Then the curtain came down, perhaps rising once more in case you didn’t get it the first time, and then the show ended and the tableau disassembled itself.

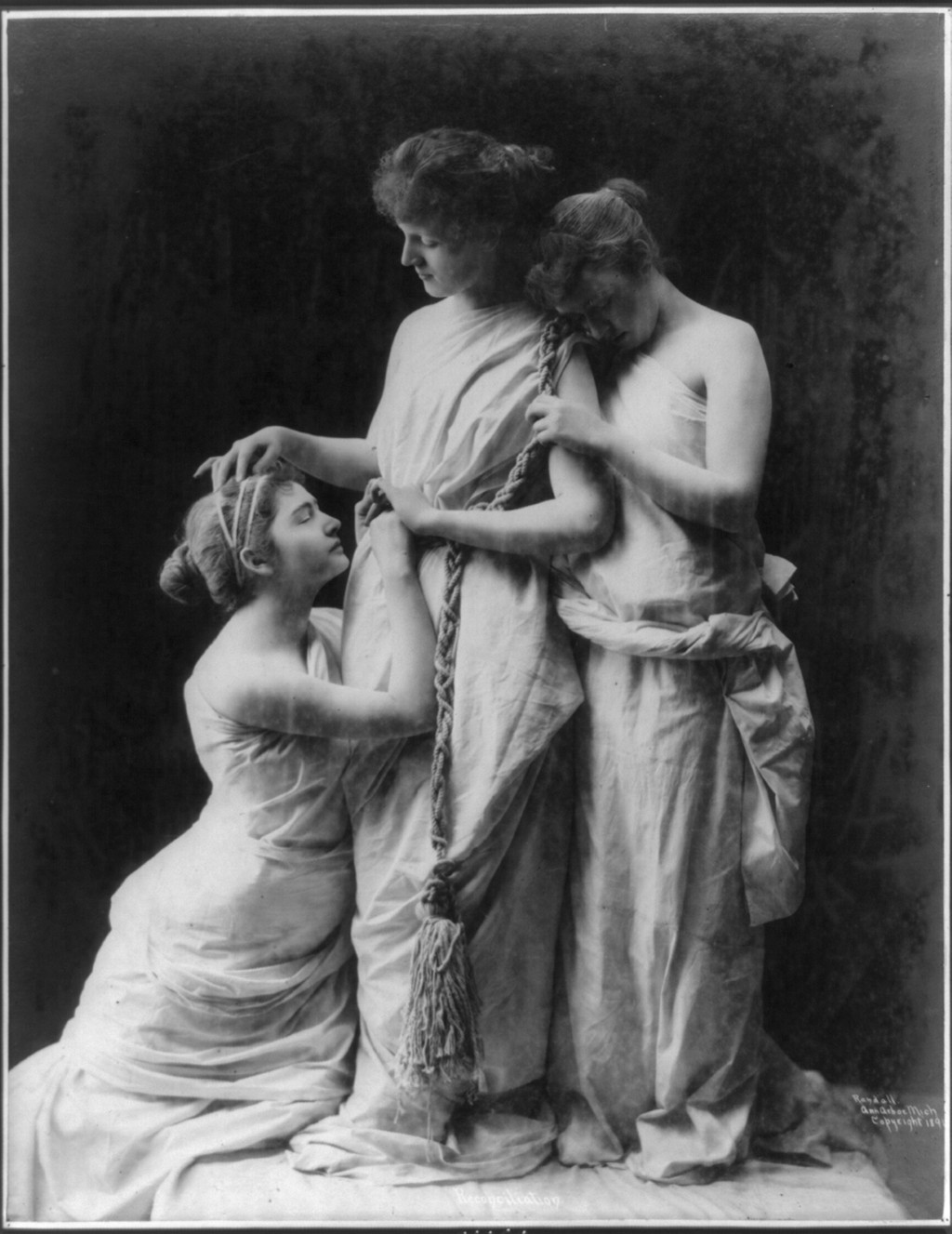

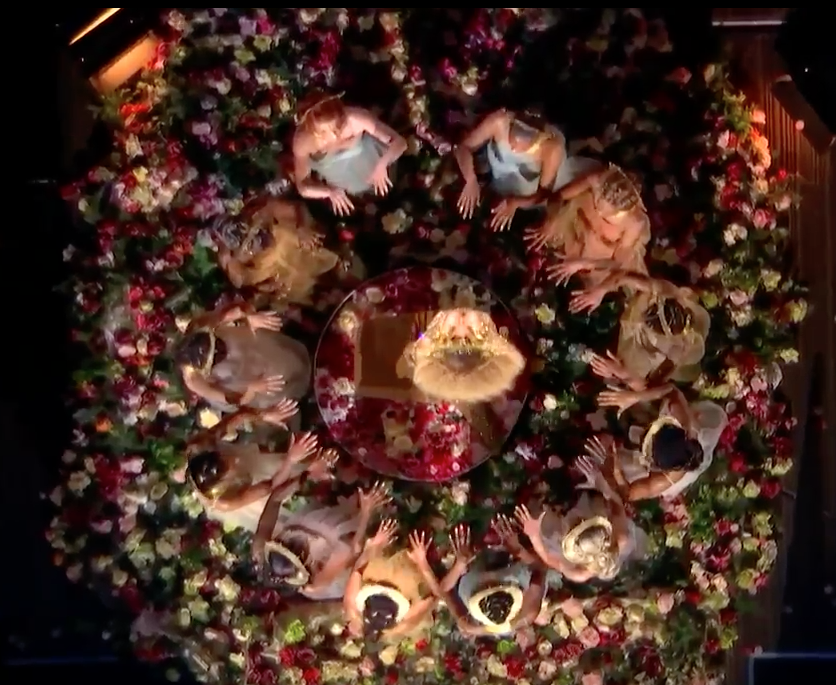

Watching Beyonce at the Grammys dressed as the sparkliest, most golden and iconographic of saints and mothers-of-God, all I could see was a twenty-first century incarnation of tableaux vivants. When she posed with Blue Ivy and Tina Knowles as a trio of goddesses in flowing robes, I saw the many photos of women in tableaux as the three Fates or three Graces. When her back up dancers created a flower crown around her, I immediately flashed to the instructions in Head’s book of how to create the visual of a wreath using women’s faces (standing on boxes of different heights came into play).

The art of posing, posing as art. I’m fascinated by the uncanniness of humans willingly becoming objects, and the fight of the living body to be still just a little longer than is comfortable for anyone in the room. It can’t be a coincidence that the popularity of tableaux vivants crescendoed in the nineteenth century just as photography crashed the art scene. The experience of being photographed was repeated in performing a frozen moment, and in turn, archives are full of photographs of those tableaux, turning art-made-flesh back into inanimate memories.

This odd game was very useful for authors with a message to hammer home, and it crops up in novel after novel in the late nineteenth century. Jane Eyre (1847) features a tableau guessing game that reveals the dark recesses of Mr. Rochester’s soul. Jane, antisocial and awkward, watches from the sidelines as Rochester and Miss Ingram act out silent scenes, including a dumb show of a marriage, to give a hint to the answer that’s revealed in the final tableaux: “Bridewell,” the name of a prison. And you say he’s daubing grime on his face, creating a swarthy countenance that makes him seem dangerous? Oh, Charlotte Brontë, what foreshadowing!

Tableaux feel like they absolutely belong in Louisa May Alcott’s books, since they are altogether domestic, imaginative, educational, and feminine. But the only Alcott tableau I’ve located is in the third and final novel of the March family, Jo’s Boys (1886), when the middle-aged Laurie and Jo put on a show with the students of her and Professor Bhaer’s school, Plumfield:

“The Owlsdark Marbles closed the entertainment, and, being something new, proved amusing to this very indulgent audience. The gods and goddesses on Parnassus were displayed in full conclave; and, thanks to Mrs. Amy’s skill in draping and posing, the white wigs and cotton-flannel robes were classically correct and graceful….”

At the end of the presentation, life is restored:

“The Professor bowed his thanks; and after several recalls the curtain fell, but not quickly enough to conceal Mercury, wildly waving his liberated legs, Hebe dropping her teapot, Bacchus taking a lovely roll on his barrel, and Mrs Juno rapping the impertinent Owlsdark on the head with Jove’s ruler.”

The restless, mischievous Americans can only embody the gods for so long before the impersonation becomes farcical. Still, the middle-aged Jo takes on some of Juno’s wifely qualities in the scene after she’s defrosted. Alcott clearly agreed with James H. Head’s claims that performing tableaux “tends to improve the mind, assimilates the real with ideal, conforms taste to the noblest standard, overflows the heart with pure and holy thoughts, and adorns the exterior form with graces surpassing those of the Muses.” It’s a church, a museum, and a makeover all in one!

Perhaps the most pointed and poignant use of tableaux in literature is in Edith Wharton’s House of Mirth (1905). In the scene that is the zenith of her life in the novel, Lily Bart strikes a pose in imitation of an eighteenth-century portrait of a woman in a loose yet clinging shift:

“Her pale draperies, and the background of foliage against which she stood, served only to relieve the long dryad-like curves that swept upward from her poised foot to her lifted arm. The noble buoyancy of her attitude, its suggestion of soaring grace, revealed the touch of poetry in her beauty that Selden always felt in her presence, yet lost the sense of when he was not with her. Its expression was now so vivid that for the first time he seemed to see before him the real Lily Bart, divested of the trivialities of her little world, and catching for a moment a note of that eternal harmony of which her beauty was a part.”

But another man watching next to Selden comments, “Deuced bold thing to show herself in that get-up; but, gad, there isn’t a break in the lines anywhere, and I suppose she wanted us to know it!”

Women in public! You might be hoping to show the world your inner beauty and true self, but some guy is always looking at your tits.

Tableaux had been part of European royal pageantry and public celebrations for centuries, but they became a household entertainment in the 18th century (first mention of the practice in British circles seems to be Goethe’s description of Lady Emma Hamilton, the famous kept woman of various Regency aristocrats, posing sexily as Circe and in other frozen “Attitudes,” and by-the-by essentially introducing neo-classical dress to British fashion). They trickled down to the middle classes and then exploded in popular culture in the 1840s in Britain, carrying on through the early 20th century in Britain and the United States. In Little Town on the Prairie, set in 1881, Laura Ingalls Wilder describes a local entertainment in a barely-there town in the Dakota Territory featuring a tableau of “Mrs. Jarley’s Waxworks” (a scene from Dickens). From their popularity in private entertainments and house parties they expanded into features of the public institutions of vaudeville shows, music halls, and exhibitions.

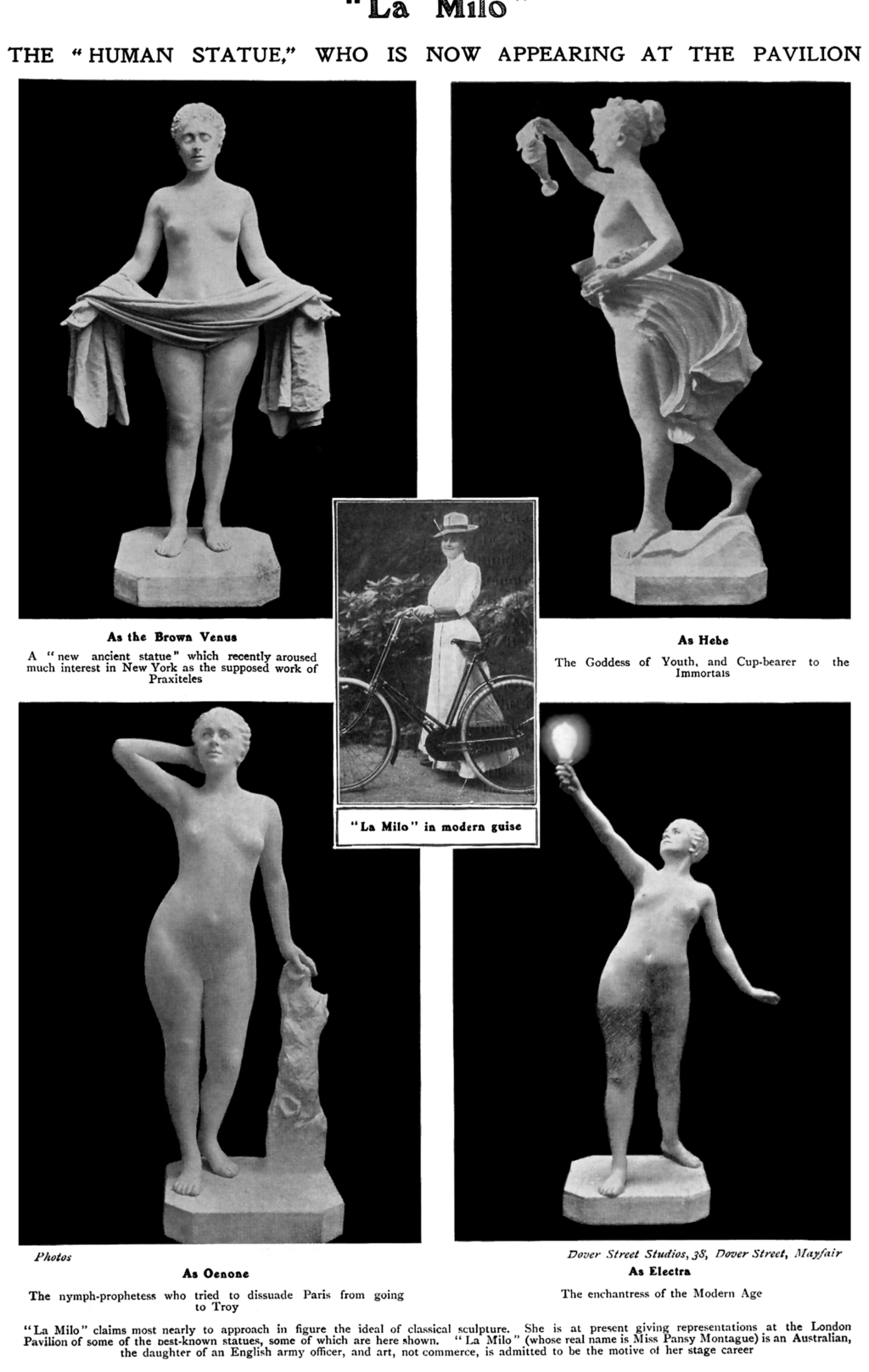

Enthusiasts like Mr. James H. Head and the owners of theatres raking in cash from googly-eyed men claimed that the practice democratized access to art, which convinced city officials and judges in London and New York to dismiss the various preachers and temperance societies who sought to have the living statue shows closed down. As long as the women on stage stayed perfectly still, their arranged and decorated bodies could be considered artistic education, not scandalous entertainment.

Eventually, elocution tutors and ladies’ clubs and societies started teaching artistic posing as part of the skills and attributes refined young ladies needed to know. Society women put on nights of tableaux for fundraisers. According to a 1902 guide to “London’s Fashionable Amusements” (seemingly written by a fan of Kipling’s “The White Man’s Burden”),

“The old-fashioned prejudice against acting or singing as a profession no longer exists. For sweet Charity’s sake tableaux vivants are also arranged, and various funds in connection with the wants of the widows and orphans who have to suffer for the benefit of Empire have been materially helped by those who have made a fashionable amusement a means of well-doing for others.”

The Victorian period was one of both sentimentalism and sensationalism, and both were captured in the performance of tableaux vivants. Moral lessons or pure ideals — like faith, liberty, or first love — were enacted, mostly by women. But in order for those women to take on those roles, they had to expose themselves to the watcher’s gaze, often in a saucy get up excused by the necessity of a convincing performance. Tableaux vivants allowed the angels in the house to temporarily become slutty artsy types. Morpeth, a painter, says of Lily in Wharton’s House of Mirth as she prepares for the tableaux: her face is “too self-controlled for expression; but the rest of her — gad, what a model she’d make!”

In the most suggestive of the tableaux vivants in Head’s 1860 guide, a woman wearing the illusion of nothing represents “Venus Rising from the Sea.” The instruction begins:

“This tableau is represented by one beautiful lady, whose costume consists of a flesh-colored dress, fitting tightly to the body, so as to show the form of the person. The hair hangs loosely on the shoulders and breast, and is ornamented with coral necklaces, while the neck is adorned with pearls. To represent the sea, it will be necessary to place, at intervals of two feet, (from wing to wing,) strips of wood, beginning at the floor of the stage, near the front, and rising gradually as they recede in the background, the last strip being two feet from the floor of the stage. After these have been arranged, lay strips of blue cambric across them; cover them entirely, and between the bars of wood let the cambric festoon so as to represent the appearance of waves….”

You in the audience were supposed to be elevated by this exposure to the purity of women and the fineness of Art, but at the same time, everyone was there either to be titillated or to show themselves off.

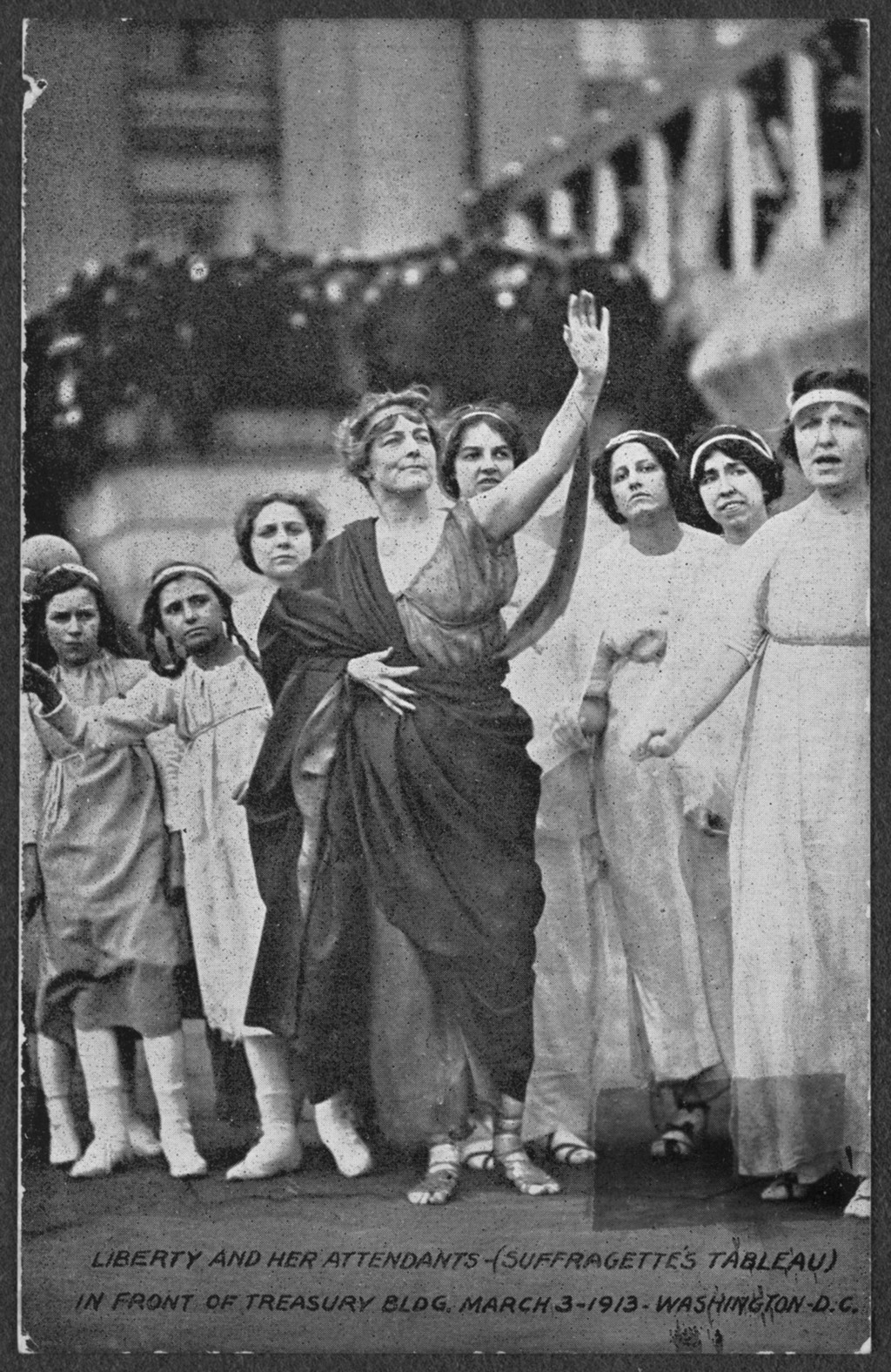

Nineteenth-century women had to negotiate a firm public/private divide that made just being in public as a woman a very dicey proposition, even more so as the century wore on toward the fin de siècle and official culture resisted the rising tide of women’s rights. Tableaux vivants made women into silent icons, but sometimes women could also take on the roles of women more powerful than simply pretty, like Joan of Arc, Florence Nightingale, Aphrodite, or Irish mythic figure Cathleen Ni Houlihan.

In a brilliant move, suffragists at the turn of the twentieth century used tableaux vivants as part of their protests and educational strategies. At women’s colleges, tableaux and other performances, particularly ones that required cross-dressing, were considered a bold grab for students’ self-determination in the face of administrative disapproval of ladies not behaving like ladies. They became a tool to allow women to be seen in public at a time when women’s position in society was fiercely contested.

Tableaux vivants were particular to a time just before the mass reproduction of art was possible, when they alleviated domestic boredom and allowed women to subvert the rules of propriety for the sake of Art. But arguments explode even today over how women can display their bodies, and when and where. The questions tableaux vivants raised in novels, on stage, and in Victorian parlors still echo in our skulls every time we strike a pose for Instagram: is this my authentic self or a performance — and who is watching?

Marthine Satris is a writer and editor in Oakland, California who really loves digitized archives. Her name is not pronounced the way you think it is.