I’m Here to Drink, Not to Talk

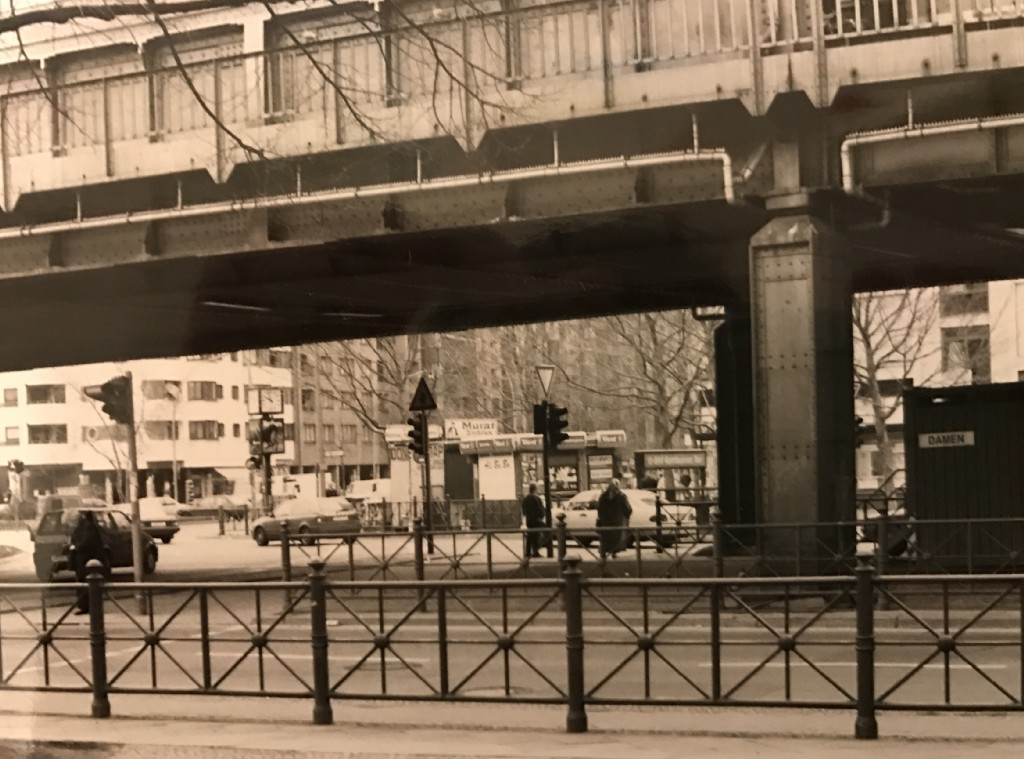

In 1997 Berlin, an illegal loft was my castle.

All the cool kids in my study-abroad program had turned down our offer of housing in the dorms. Because the only cool place to live in Berlin in 1997 was an authentic Berlin WG (Wohngemeinschaft, literally “living community,” the name for an apartment shared with someone who isn’t one’s family). The only problem was, any place that was available to the likes of me (budget: 300 deutsche marks per month, aka $175) was nightmarish, such as a windowless closet I went to see in the desolate eastern district of Treptow, which might have been able to accommodate a twin mattress on the floor if it were placed diagonally.

Right before I gave up, my sole German friend, Gertrud*, invited me to drinks with her and Paul, an old schoolmate of hers from Chemnitz, a town in the former East Germany that used to be called Karl-Marx-Stadt. The good news is that if you are in a terrible mood and don’t feel like talking to anyone, going out drinking with Germans is exactly the right thing to do with yourself. There’s an old joke related by Walter Benjamin, about three authors who are out at a pub. After fifteen minutes of silence, one of them says: “It’s hot today.” After another fifteen minutes of silence, the second says, “No wind, either.” The third one, after another fifteen minutes, snaps: “I came here to drink, not to talk!”

Correspondingly, that night, the three of us sat in silence, lit cigarettes, smoked them, put them out, lit more. After the requisite hours of staring, Gertrud became the evening’s abject blabbermouth.

“Na du,” she said to Paul. “Rebecca’s looking for a place to live.”

At that, Paul’s small round glasses almost flew off his pale visage. “We have one for you! In our Fabriketage!” he said, using the German word for loft. “How much can you pay?”

“Three hundred.”

“That’s exactly what it will cost!”

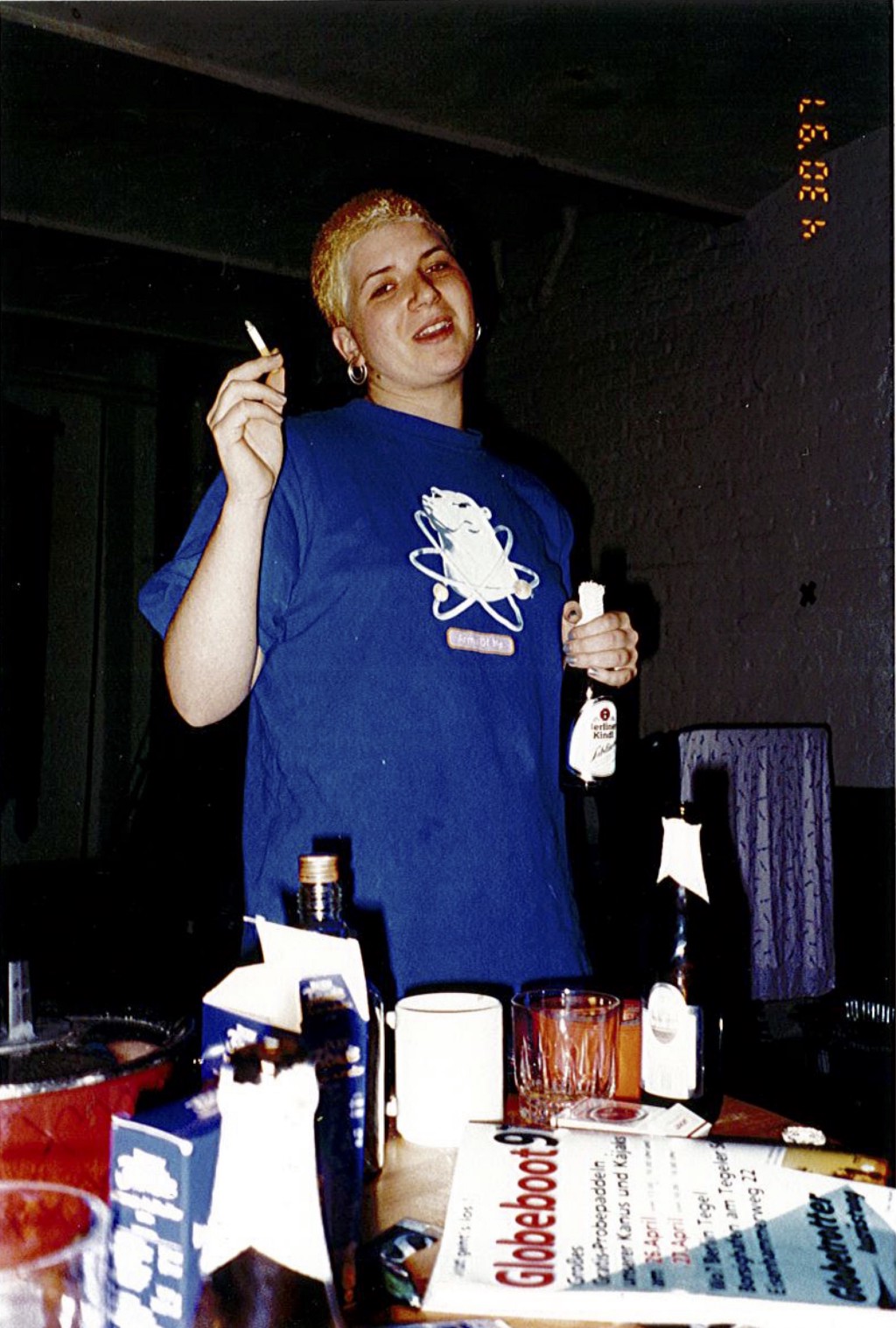

But before I could move in, I had to pass an audition with Paul’s four loftmates, to be held in the form of three hours of silent glowering, a.k.a. socializing, at one of newly-reunified Berlin’s omnipresent illegal basement bars. There I met Leonie (a formidable urban-planning student who never wore a brassiere), Rolf (tiny, handsome and dour, like Dieter from Sprockets but with perfect cheekbones), Detlef (a shy, towering babyface from Hamburg), and Johannes, the friendliest of the bunch, by which I mean he glowered silently at me while proffering his open pack of Lucky Strikes. Four increasingly illegal bars later (one of which, in lieu of a little girls’ room, had a toilet shoved in the janitor’s closet), it was nearing five in the morning, and I was no closer to knowing whether or not I’d be allowed to join the loft. Paul simply kissed me on each cheek and told me to mach’s gut as I dragged myself onto a night bus, freezing and dejected.

But halfway through my first pouty coffee the next afternoon, Paul called me at my homestay, and instructed me to come by what was apparently my new home, drop off as much of my stuff as I could carry, pick up my new keys, and would I please bring the three hundred deutsche marks in cash?

The place went by the official moniker Loftschloss, or “loft-castle,” which was a play on the word Luftschloss, which literally translates as “air castle” but is the German word for “daydream.” And it was the stuff of daydreams, if you daydreamed about living in a midcareer David Bowie video, which I obviously did.

I’d barely had a chance to peer around the vast, definitely-industrial-looking space — pipes visible everywhere, unfinished walls, and not a residential fixture in sight — before Paul thrust into my hand the most curious set of keys I’d ever seen. There was a regular-sized one for the door of the loft and a bizarre, giant, cartoon-looking thing wider in circumference than a number-two pencil, with no method of affixing it to any sort of chain. This, Paul explained, was for the outer door to the building, whose lock hadn’t been updated since before the war. You operated it by sticking one end of the key into the keyhole, turning it around until it caught, then swinging the door open, walking through, and pulling the key out the other side of the door. You had to unlock the door from the inside to get out, as well as from the outside to get in. I guess Germans assumed nobody would be careless enough to set a fire.

It was my official rule never to turn down an invitation from one of my the Loftschlossers, because each one took me to a weirder place than the last, deeper into the Berlin that my Time Out guidebook had never seen. One night, it was a tire-fire party in the backyard of a squat, whose residents performed their toilette in a full-sized bathtub placed on top of two adjacent stoves. The next week, it was onto the handlebars of Johannes’s bicycle with me, as he careened through the deserted streets of Mitte at four in the morning, to a bar called Dienstagsbar because it wasn’t a bar so much as a random gathering of people with cool hair in a gravel-covered vacant lot, and it only happened on Tuesdays. The week after that, it was a pop-up art show by one of Leonie’s friends comprised entirely of stuffed-panty-hose sculptures, and it took place inside a filthy abandoned bunker. Sometimes I felt like my roommates just woke up, combined a bunch of random nouns and verbs, and then decided to go do whatever that was.

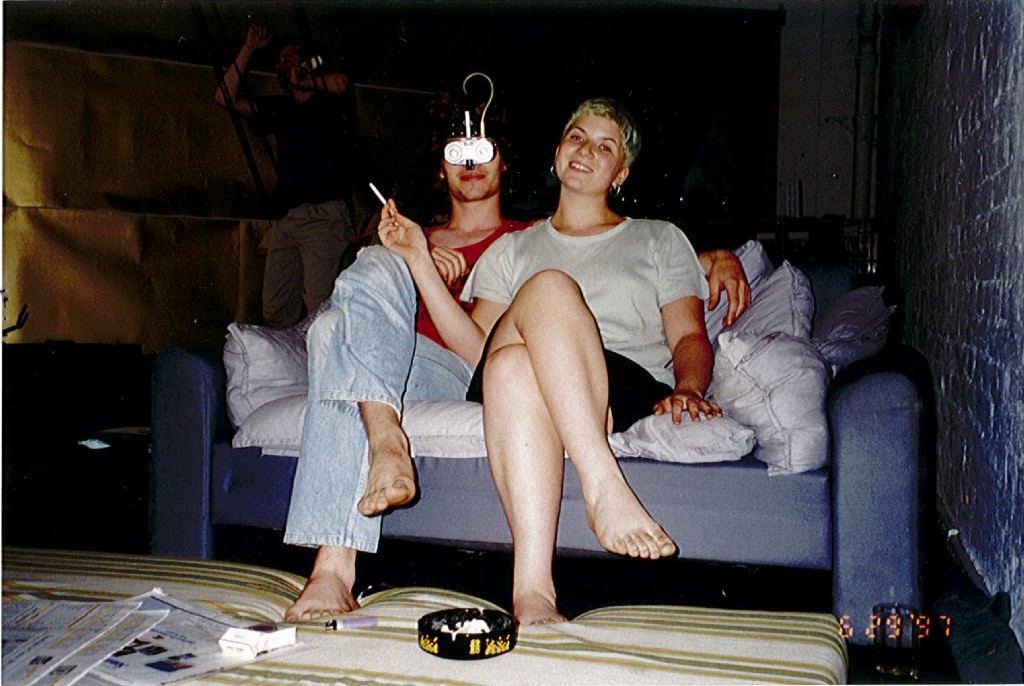

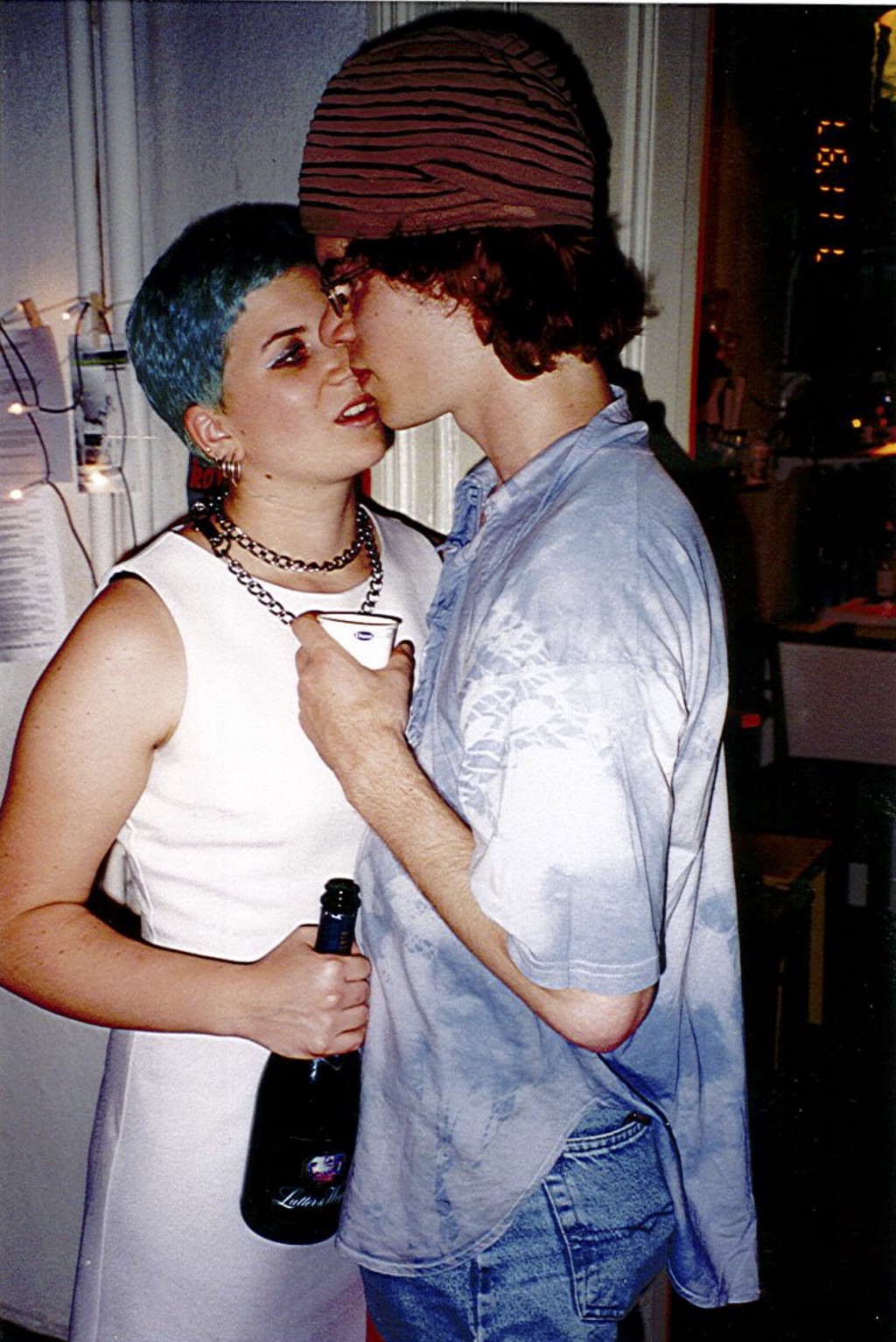

In the late spring, we threw what was supposed to be a rent party, but on which, I am fairly certain, we lost money. It was essential that this party be perfect, because I’d invited all of my study-abroad classmates and it was imperative they see firsthand exactly how cool my life was. And I think that when the magical day arrived — milk-crates full of Hefeweizen procured, peculiar elder-flower punch mixed — they had a good time. It was hard for me to tell, because for most of the party I was stuck on “key duty,” which meant I was responsible for using my giant Disney Schlüssel to let some partygoers in and others out, at random and somewhat indeterminate intervals made ever more complicated by the fact that nobody had a mobile phone yet.

Our guests stayed so late into the wee hours — dancing; swinging from the ceiling; staring at each other wordlessly and then pairing off into life partners — that Paul had to blow his saxophone directly into their drunken ears to get them to stumble out. When I finally trod into my corner of the living room at eleven the next morning, I found a strange guy sleeping in my bed.

“Hallo,” I said. “I live here.”

“Huh,” he said, and puffed languidly on the cigarette whose ashes were falling onto my sheets.

I slunk back into the kitchen and grabbed one of the few remaining bottles of beer. I popped off the cap using one of the four cigarette lighters that lived permanently on the kitchen table, then used the same lighter to ignite a Lucky Strike from one of Johannes’s half-open packs.

As I took a slug, Paul shuffled in with his hair sticking straight up and his shirt on backward. He nodded, grabbed a bottle for himself, and handed it to me to open, since I already had a lighter in hand.

After about fifteen minutes of sipping and staring out the window through a smoke cloud, he said: “You’re up early.”

I nodded.

After about five more minutes, he said: “It might be cold today.”

I looked vaguely in the direction of the living room, ashed my cigarette, yawned. We were, after all, there to drink, not to talk.

*All names have been changed.