Astrology is Fake and Oxen Might Be Rats

You’ve probably been getting your sign wrong all along.

For most of my life, I believed I was an ox.

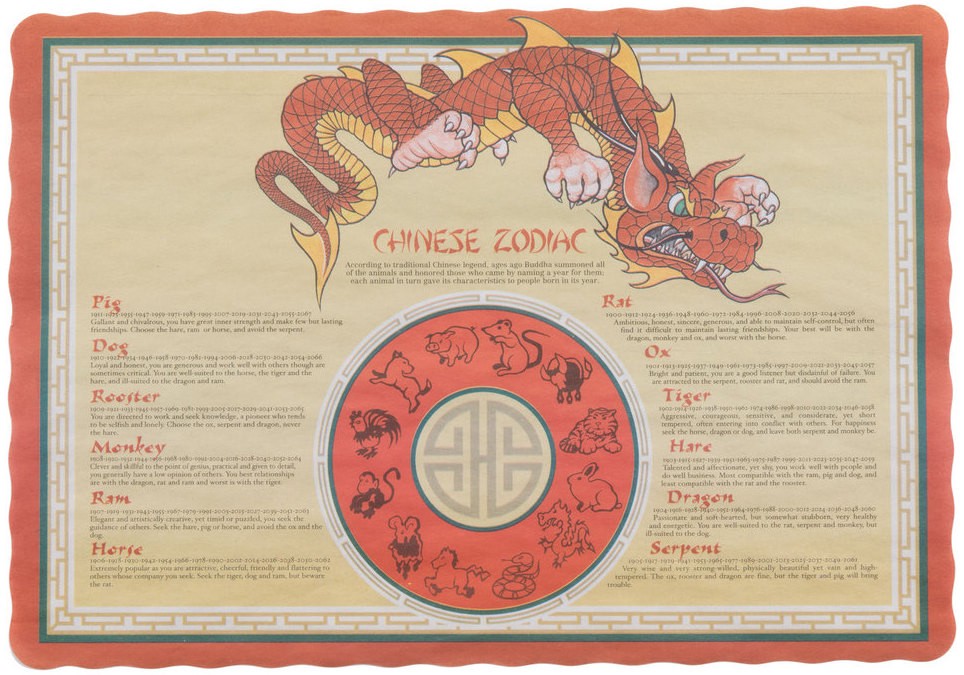

According to all the paper placemats in every Chinese restaurant I had ever been to, 1985 was the year of the ox. Most of my friends were oxen, too, save for the few older kids in my class who had been born rats in 1984.

A compelling distraction while we waited for our sweet and sour General Gao’s rangoon chop suey whatever, those wheels of fortune determined my father was an independent and hard-working horse, my mom a kind and gentle sheep, and my brother a confident and passionate dragon, and I was an industrious and stubborn ox.

But we Americans have all been blindly accepting our characteristic fate based on a rough translation and incomplete information.

It only occurred to me when I moved to China that of course those Chinese Zodiac years don’t precisely match up with the new year that most of the world celebrates on January first of the Gregorian calendar. Chinese New Year actually falls somewhere — seemingly arbitrarily — sometime in January or February. My birthday is February 3. Have I been a rat this entire time?

The further I looked into the Chinese zodiac, the more complicated it got. Most Chinese people use the lunar new year date as a reference point for the start of the zodiac year, mostly because the two-week festival, and all its decoration, welcomes the new animal. The lunar year varies widely, anywhere from January 21 to February 20, depending on how many moon cycles fit into one year. Some years have an entire leap month to account for the extra time — there are thirteen lunar months this year.

Given this lunar irregularity, it turns out that for fortune-telling and astrological purposes, it is preferred to use the solar calendar start of the year, known as the start of spring or lichun for the start of the birth year animal. In the Chinese calendar, the start of spring falls around February 4th, give or take. This year, the start of the solar new year, or the start of spring, is actually February 3, 15:34 UTC (Coordinated Universal Time).

This means that all babies born between the lunar celebration of Chinese New Year and the solar start of the year fall into that ambiguous space between the year of the monkey and the rooster, making zodiac identity confusing even for the Chinese. And basically everyone else going by the Gregorian January 1 start are just fooling themselves with Americanized versions of fortune and food that you wouldn’t find anywhere in China.

In 1985, the solar start of spring fell at February 4, 05:12 (GMT+8). Lichun isn’t relative, because it’s based on when the sun reaches the celestial longitude of 315°, so that’s globally standard, making my relative local sunrise concern moot. This puts the solar start of the year of the ox at 4:12 P.M. EST on February 3 local time. So, I just barely made it into the year of the rat, when I very easily could have been an ox if I were born hours later.

Appropriately, I like to think this makes me a cusp rat, cleverly crossing the flooding river on the back of the ox, reaching the bank and scurrying ahead to win the race to be the first animal named at the start of the zodiac calendar as one version of the legend tells it.

I never gave too much thought to these characteristics of Chinese zodiac signs, as they always seemed to broadly generalizable to me. Could the attributes of the rat and the ox apply to my entire cohort of classmates? I identify much more with my western astrological sign, Aquarius (and Aquarius rising in my natal chart). But even that designation has come into question in recent news, as astronomers have suggested a modernized zodiac that includes thirteen constellations, changing 86% of the existing monthly breakdown. I stand with Susan.

Like the complexity of the natal chart in western astrology, those paper placemats also fail to introduce the complexity of the pillars of Chinese Zodiac philosophy. Detailed readings look at not only birth year, but also to month, day, and hour, attributing animals that reflect our inner, true, and secret selves, respectively. That makes me a public rat, an inner ox, a true chicken, and a secret dragon. Further punching in these detailed coordinates in on an astrology site reports me to be a “black chicken born in the year of the green rat” and my lucky element is water. Sounds more like a recipe for soup than my destiny. But I like the idea of a badass secret dragon tattoo.

As we enter the year of the fire rooster* (a designation that seems surprisingly appropriate to characterize the outspoken and attention-seeking orange crested cock who has made official entrance on the world stage) these cross cultural conflicts of understanding of our place in time lead me to believe we should all just refer to moments of significance — as we should all international conference calls — on based on UTC time, the ultimate, unambiguous standard of global timekeeping. In the meantime, I’m starting a petition for every paper placemat to be updated with an asterisk explaining the January/February time warp pointing to a lunisolar calendar chart on the reverse for reference. Because if we’re going to believe fake things like zodiacs, they might as well be accurate.

* By the way, any roosters thinking that this is going to be your lucky year, you are mistaken. On the twelve-year cycle of your birth animal, Chinese tradition is to wear red underwear to ward off any bad luck heading your way. Also, they have to be gift underwear.

A tech critic, Sara M. Watson hibernates when mercury is retrograde.