Marriage Proposals

Why has the tradition stuck?

In an era of viral flash-mob proposals, it can be helpful to remember that things might always be worse: back in the stone age, a caveman would “tie cords made of braided grass around” one lucky cavewoman’s “wrists, ankles and waist” in order to signal to all that he’d decided to take a bride. The tradition may well be apocryphal — Reader’s Digest’s engagement ring timeline doesn’t source the factoid — but the image nevertheless resonates: a woman, patient and submissive, waiting for a man to literally tie her down.

The codification of the engagement ring — in the Western world at least — is traceable. An old Anglo-Saxon tradition “required that a prospective bridegroom break some highly valued personal belonging. Half the token was kept by the groom, half by the bride’s father.” For wealthy men, the “valued personal belonging” would almost certainly be “a piece of gold or silver.” By the ninth century, Pope Nicolas I was requiring an engagement ring — made “of a valued metal, preferably gold, which for the husband-to-be represented a financial sacrifice” — as part of a “statement of nuptial intent.” The first diamond engagement ring was proffered to Mary of Burgundy in 1477 as pledge of Archduke Maximilian of Austria’s troth, but they didn’t become more widely popular until 1948, when the advertising firm A.W. Ayer & Son created the slogan “A diamond is forever” for the jewelry company De Beers.

So, too, the codification of an official engagement period. In the thirteenth century, Pope Innocent III “extended to the whole western portion of Christendom the custom of publishing ‘banns of marriage.’” The point was not, as it often is now, to give the couple time to plan a wedding. (After all, if they had not been promised to each other by their families years before, they were nevertheless likely being united for financial rather than romantic reasons.) Rather, by announcing that a man and a woman intended to marry before the actual wedding took place, those who knew of “any just cause of impediment” to the union were given the opportunity to speak — or, presumably, forever hold their peace.

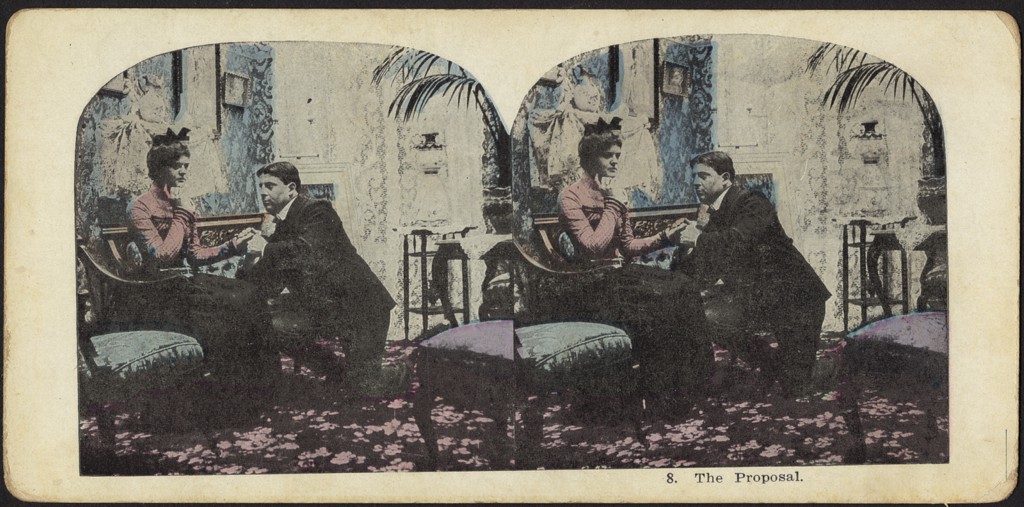

There is more dispute over when and why it became customary to kneel before the presentation of the ring that initiates the engagement — does the gesture have its origins in the customs of courtly love? In those of religious practice? — but one aspect of the engagement ritual is impossible to trace because it springs not from a decree but from history, which is to say patriarchy. Why, in a heterosexual relationship, is it the man, almost always, who pops the question — often, as the word “pops” suggests, by surprise — and not the other way around? The answer is simple: because it always has been.

Search for “why do men propose marriage” and you won’t get a Vox explainer on why men are the ones who get down on bended knee to offer their beloveds diamond rings. You’ll get headlines like “The reason why men marry some women and not others,” “Why Won’t He Propose,” and “Should a Woman Ever Propose Marriage?” (short answer: no) above articles pegged to straight women who wonder why their partners are stalling but are unwilling to ask for fear of appearing too needy.

Despite the fact that women have, in the hundreds of years since Maximilian slipped that diamond ring on Mary’s finger, gained the right to own property and vote and hold elective office, they still in overwhelming numbers decline to propose to the men they may already live and have children with. A 2012 study of 227 heterosexual undergraduates at the University of California, Santa Cruz found that “two-thirds of the students, both male and female, said they’d ‘definitely’ want the man to propose marriage in their relationship.” The same study found that “2.8 percent of women” surveyed would “‘kind of’ want to propose.” No one, male or female, was “definitely” in favor of the woman in a heterosexual relationship proposing.” (I couldn’t find an analogous study documenting proposal norms among same sex couples, but Gawker, the Huffington Post, and Reddit all agree that the usual rules don’t apply.) I grew up in Santa Cruz; it’s popular with surfers and wearers of hemp shoes, the kind of place where you get a dirtier look for smoking a cigarette on the street than for smoking a joint. In other words: not a bastion of social conservatism.

It’s certainly not unheard of for a woman to propose to a man, or for couples to propose to each other. And the question, today, rarely comes as a true surprise; men are typically ready to propose about six months after “receiving hints or discussing it with their partner.” Still: the idea of a woman asking the actual question remains preposterous enough that the New York Times dedicated a Styles piece to the one day every four years — Leap Day — when such boldness is, by tradition, permissible. (Legend has it that this “Ladies Privilege” was negotiated by an Irish nun who would later be canonized as St. Brigid in the fifth century.) Even so, women who take advantage of the opportunity have been, per professor Katherine Parkin, “portrayed as ugly, mannish, crass or desperate.” Just three years ago, a female columnist for UK’s Telegraph confessed that she wanted to be proposed to for “psychological” reasons “despite the fact that I am a fully paid up feminist of the non-hairy armpit kind.”

Though western women are, mostly, no longer required to bring dowries into marriage, it’s not hard to read, into the enduring female reluctance to propose, a lingering sense that women — even or perhaps especially when they play by the rules, behave stereotypically — are a kind of burden. It’s a heterosexual woman’s catch-22: we’re supposed to want to get married, but if we advertise that desire too loudly, we become unmarriageable.

My husband and I discussed getting married three weeks after we met. “Discussed” is perhaps overstating it. It was late, a Friday or a Saturday night, and we were talking. “If this ends,” he said, of our romance — long-distance then and already a whirlwind — “it’s the end of a marriage.” “Then ask me,” I said. More than words, I wanted certainty. I couldn’t be secure in my own feelings unless I knew them to be reciprocated.

If women are not sure of their own desires, they’re sure at least of what they’re supposed to be. (Women, a study has shown, are typically ready to marry their male partners four months before said partners come around to the idea.) It’s heterosexual male desire — for anything beyond sex — that remains, at least in the popular imagination, not merely elusive but antagonistic; that demands confirmation.

If it’s true that the risk of asking continues to fall, in heterosexual courting rituals, disproportionately on men, it must also be said that their risk is often rewarded. All too often, no matter the answer, women are punished merely for daring to pose the question.

Miranda Popkey is a writer based in St. Louis, Missouri.