Parenting by the Books: ‘On The Banks of Plum Creek’

When a doll is more than just a doll

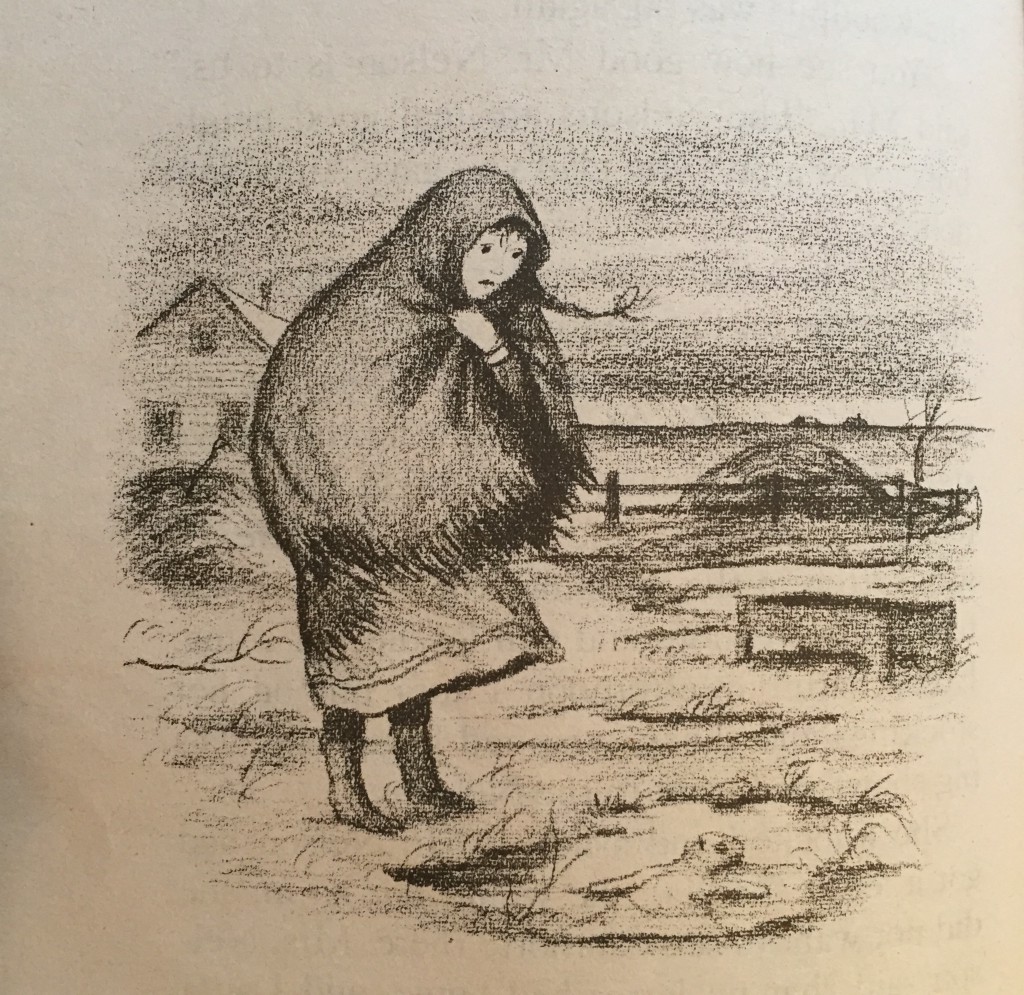

Recently my five-year-old son caused me to revisit one of the most painful scenes of childhood literature: when Ma forces Laura to give away her beloved rag doll, Charlotte, in On the Banks of Plum Creek. To briefly recap for those few who do not have the scene burned into their psyches: the Ingalls’ neighbors, the Nelsons, come visiting, and their awful toddler Anna demands to bring the doll home with her. Ma forces the exchange, only for Laura to discover days later that Anna has discarded the beloved toy in a freezing puddle of water. When we got to the moment where Laura comes upon darling abandoned Charlotte in that puddle, my son welled up with tears.

I asked him what he was feeling: what did he think about Ma making Laura give another child her beloved doll? “Ma is mean,” was his emphatic reply, as he clutched his own lovey, a little square of fabric covered in tags, to his chest. And with this interpretation, he joined a long line of readers who agree: Ma’s directive is over-the-top generosity at best, cruelty at worst. She is wrong to make such a demand of her child. As I reread the book this time, though, a huge neon finger appeared above my own lifelong complaint about Ma’s thoughtlessness over the doll. Flashing red at me, it begged me to reconsider.

The reason we don’t like Ma here is not so much that she fails to empathize with her child, but that she stands in the way of what Laura wants: to be possessive and individually sated, rather than socialized. Our fantasy is that society’s needs and the individual’s desires aren’t opposed to one another; Plum Creek not only reminds us that they are, but also that, historically, mothers have borne the brunt of navigating the abyss between the individual and the social. And that further! mothers do this work all while navigating their own desires and taking care of social systems that only precariously ensure their survival.

The drama of Charlotte the Doll shows how our culture crafts mothers into socializing and civilizing forces and then calls them killjoys for doing the work of managing the derangements of individual desire. Our desires — to possess, to act as if unencumbered by others, to be selfish and sated — more often than not hurt others. This isn’t news to Ma Ingalls, a woman repeatedly brought to the brink of death and starvation by Pa’s cheerful belief that what he wants for himself — light out for the territories! take this land for my own! no town in sight! — harms no one. Ma is the person across eight books with the most intimate access to the cruelty inherent to individual desire, and a pretty deep understanding of what might happen if those desires were given free reign (total social breakdown!), and we sit back and call her a bitch. Let us inquire into this.

The clearest explanation for why Ma would ask Laura to give her beloved doll away is a version of socialization that subordinates the self to others. “We must not think only of ourselves. Think how happy you’ve made Anna,” Ma asks Laura to consider. Put this way, Ma’s request feels like good, or at least recognizable, parenting and like some of the justifications I’ve offered my own kids for why they should share or take turns with toys.

Today’s “sharing” might be the weaksauce version of the nineteenth century’s “giving,” but both are ways that humans try to assuage the force that individual desires can wield. My house is full to bursting of conflicting desires: I want a minute to myself, the five-year-old wants ice cream, the three-year-old wants his little hands to work better. The end result is often everyone sitting in a huddle together wailing and gnashing. We all want so much, so differently, and those desires rarely align.

This is a bleak vision, underscored by the even bleaker passage in Plum Creek where Ma finally notices what losing Charlotte has done to Laura: “[Laura] did not cry, but she felt crying inside her because Charlotte was gone. Pa was not there, and Charlotte’s box was empty. The wind went howling by the eaves. Everything was empty and cold” (232). Ma apologizes; she hadn’t known that Laura felt so deeply about the doll. Together they stitch up the rescued doll that Ma gives Laura a pass for “stealing” back, and the episode ends on a creative, rather than destructive, note.

But I want to pause here to note the detail that exacerbates the conflict between Ma and Laura over Charlotte the Doll in the first place: Pa is gone. He’d walked on foot hundreds of miles to earn money helping with a harvest elsewhere because the Ingalls’s crops were decimated by a plague of grasshoppers. Ma and the girls don’t know where he is and when he’s coming back.

To put it another way, winter is fucking coming and it’s not that the doll becomes a trivial concern in such circumstances, but that it becomes intensely meaningful for both mother and child under these conditions of scarcity. The doll, then, is safety and home for a child whose sense of safety and home is eroded with each day her father fails to return. But for Ma, the doll is also an item to barter for good will from a neighbor woman under whose (meager) protection she might find herself, should her husband fail to come home. Is it right for Ma to demand this sacrifice of her daughter? Probably not. Is it likely related to her own womanly and motherly instinct for survival? Definitely. Have generations of readers read her as a bitch for acknowledging that we have to labor daily in a hundred small ways to take care of society unless we want to starve? C’mon.

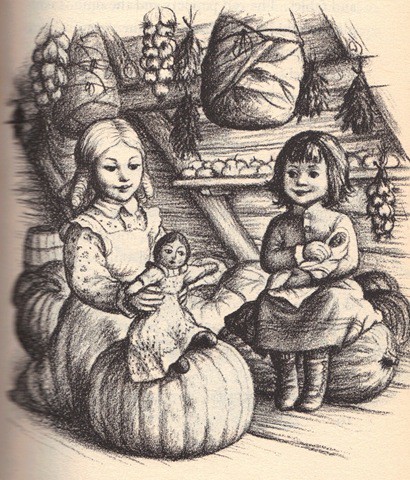

A doll is never just a doll, ask Freud or Ferrante, or Esther Summerson who so creepily buries hers in Bleak House. The Little House series abounds in dolls: Ma’s little china shepherdess, Nellie’s china doll, Mary’s rag doll Nettie. Dolls and loveys are opportunities to practice love, to transfer the overwhelming drives a young child feels toward a parent to something outside the immediate family system. They offer ways to navigate relationships with other children and caregivers, or to mark life stages or even class status.

They also allow children to practice cruelty. Consider the troubling end of Little House on the Prairie, a book that tracks the Ingalls’s lives while they live on Osage land in Kansas. (We’d thankfully skipped this relentlessly racist and colonialist book at my son’s request.) During the entirety of LHOP, Pa has been promising Laura that she would be able to “see a papoose,” as if a “papoose” were a sort of doll one could buy at a store or see in a museum. Laura finally gets her chance as her family lines up to watch the exiled Osage process pass their homestead. Laura sees a mother with a young child in a basket, and utters one of the only loudly voiced demands she’ll make across eight books: “Get me that little Indian baby.”

Like the horrid Anna Nelson who bawled and cried until she got her way, who ripped precious paper dolls in half and discarded beloved rag dolls in the freezing cold: Laura, too, is an acquisitive, bad-acting horror, ravaged by the currents of the broken and cruel world in which she lives, and she wants what she wants.

Parenting provides amazingly unfiltered access to states of desire because children are so good at expressing theirs and at thwarting our own. The daily labor of parenting requires navigating those desires without looking at them too intently: we are not meant to give children most of what they want and we simply cannot inquire too deeply into how many of our own desires are going unmet. The work of socialization has to be done, but the force of the desires that it tames doesn’t exactly dissipate. We might not ever know exactly what Ma Ingalls wanted, but we do know that she intimately understood the power of want, and how combustible social and familial experiments are in the face of that power.

“Mommy,” my son said as he softly caressed my face one day during nap time, “I want to poke my fingers into your skull.” I’m not looking for recognition for not always giving him what he wants. Rather, I’m taking my own notes on how close we always are to going up in flames of our own making, and whispering a little thank you to Ma Ingalls for always being there with a bucket of cold water.

“Parenting by the Books” is a series about parenting and classic literary texts.

Sarah Blackwood is editor and co-founder of Avidly and associate professor of English at Pace University.