Parenting by the Books

A new column about parenting and classic literary texts

Last spring, my students and I were immersed in a conversation about difficult cultural theory, when our attention was shifted to the sounds of someone vomiting in the hallway outside. The sound was visceral and cinematic, the liquid splashing the linoleum floors. (The conversation, if you must know, was about Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s “The Culture Industry,” but it seems almost too on the nose to pair that fact with the vomiting).

I popped my head out of the door. “Do you need help?” “Yes,” the young man miserably nodded. I motioned him to the bench nearby, told him to sit tight, and then did some running around to get help cleaning up in the hall. Once that help was on the way, I checked that he was sufficiently recovered to make his way back to his dorm room, and was back in the classroom within, like, seven or eight minutes, no big deal.

When I sat down, my students were agape. “You acted so quickly!” “You knew exactly what to do!” “I think most of my professors would have just closed the door and kept discussion going.” But then the most dreadful comment of all: “You must be a mom.”

Infuriating! because we live in the world we live in, and not only do I not want to be “a mom” to my students but I actively try to redraw their perception of me as exactly NOT that. What did this comment mean for their understanding of me as an intellect? Should I have closed the door and kept discussion going? It was as if they had found me out and I had morphed in front of their very eyes into someone in bad jeans and unkempt hair, scrabbling around, mindlessly looking for a lost sippy cup and wiping snot from someone’s face.

Recently, literary critics have begun to identify what looks like a sea change in the gulf between mind and mom, arguing that many works of literature from the last decade or so have begun to dismantle traditional tropes of maternity, family, and domesticity as states of intellectual placidity. The names of the authors of these works form their own kind of chant these days: Rachel Cusk, Jenny Offill, Maggie Nelson, Sarah Manguso, Rivka Galchen, Elisa Albert, Eula Biss. If this is indeed a literary movement, it’s exciting, though certainly partial (mostly white, mostly cis, mostly straight). These voices are, as Parul Sehgal writes, “freshly interrogating the family as experience, institution, and site for intellectual inquiry.” They are needed and to be celebrated.

But they are also part of a longer history that stretches back far beyond the twentieth century, of smart and challenging writing about parenting and childhood. We are not, in the twenty-first century, the first to discover that moms are gnarly, children vulnerable and perverse, parenting gutting, and the family a precarious experiment.

In the spirit, then, of both the new and old writing on motherhood, family, and children, is this column — Parenting by the Books — where I’ll use classic literary and historical texts to think through contemporary parenting: breastfeeding, sleep training, sharing, attachment, sexuality, and more. There is an enormous industry that produces metric tons of parenting advice books and studies around all of these issues. Let’s not read any of it! Seriously! No more studies! What more do we need to know than that even the ur-mother of American culture, Marmee March, cops to feeling “angry every day of [her] life?”

Of course, even when we know this about Marmee, it’s still often hard to know it. What is it about parenting that makes it feel like you never knew how it would be, despite so many people and texts, across centuries, desperately trying to communicate and represent in words how it is? Despite being lousy with nieces and nephews and well-versed in feminist theory, I still feel like I missed the real significance of the many philosophies of parenting/birth/mothering/children that I encountered during the decade-plus of serious literary study that preceded me having children of my own.

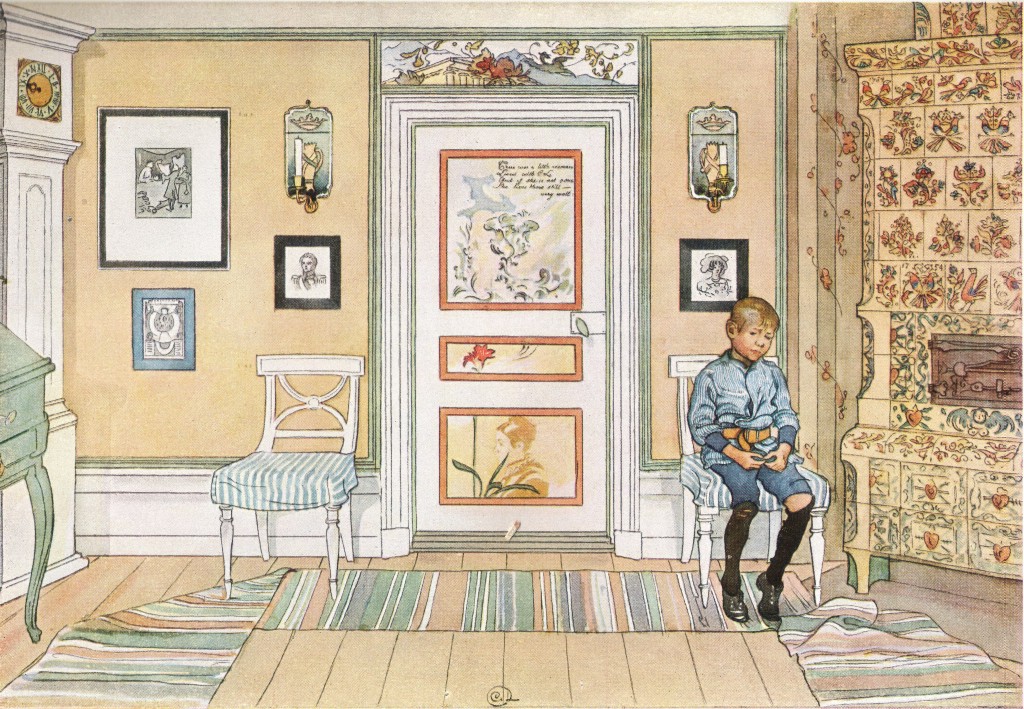

Much of the problem is that “how parenting is” has always been (and still is) shot through by cultural messages and fantasies about childrearing and domesticity. Even Marmee herself compromises the force of her description of her own anger by making her acknowledgment of it into a lesson about how to manage and disperse that anger. It’s hard to see figures like Marmee clearly through the various fogs that occlude the embodied experience of parenthood: all of the sentimentalizing, catastrophizing, aggrandizing, and marginalizing ideologies of domesticity that blanket our perceptions. But now that we’re here, in this creepy, foggy gothic house of lost sippy cups, let’s take a peek at all the crevices and corners into which the extreme weirdness of reproductive domesticity has been swept and ignored.

In the end, I don’t actually think that my students saw the disconnect between a mom and a discussion of Adorno and Horkheimer that I worried they might. More power to them, since if there’s anyone who can make sense of those cranky old grandpas, it’s a mom. Consider how, underneath their futile railing against the (feminized) seductions of moving pictures and jazz, Adorno and Horkheimer were onto something that moms know intimately: “Existence in late capitalism is a permanent rite of initiation. Everyone must show that they identify wholeheartedly with the power which beats them.” Reproductive domesticity has never been a demure and sedate intellectual space, no matter how much we have identified with the powers that have told us it is.

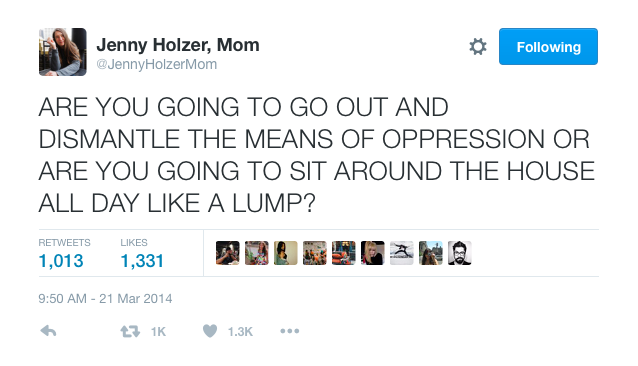

In other words, as @JennyHolzerMom might put it,

Move over theory bros, Marmee is here.

Sarah Blackwood is editor and co-founder of Avidly and associate professor of English at Pace University.