Monstrous Births

Pushing back against empowerment in childbirth

In 1847, Scottish physician James Young Simpson began experimenting with chloroform to help ease the physical pain of childbirth. By 1852, Queen Victoria was using it to dull the sensation of labor, which she described as “a dreadful thing,” “being like a cow or a dog.” Once the royals accepted pain management in birth, many others quickly and eagerly followed suit. The pain of childbirth had for millennia been interpreted as a form of deserved punishment for women. If childbirth no longer had to be physically painful, what would happen to the moralizing values that were once associated with that pain?

That’s a rhetorical question, obviously, because we still have plenty of ways to understand childbirth in moralizing terms. Jessi Klein’s recent opinion piece for the New York Times, “Just Get the Epidural,” highlights how contemporary birth is often framed as something one can do correctly or incorrectly, and how this framing is yet another baroque form through which women discipline one another. What’s clear is that even progressive feminist discussions about birth continue to draw from a pre-modern sense of it as morally charged: something that can be done in a right or a wrong way. During my first pregnancy, I was seduced by these feminist ideals about childbirth and thought that the way I went about it would be representative of something about me and my strength. Childbirth would be — in a word that continues to have bizarrely strong currency for pregnant women — empowering.

But after having two babies, as much as I want to side with Ina May Gaskin, whose Guide to Childbirth opens with the assertion that “the best way I know to counter the effects of frightening stories [about childbirth] is to hear or read empowering ones,” I cannot. Childbirth is not empowering. It’s grisly, frightening, and astonishing stuff. Which is not to say that it can never be pleasurable or rapturous, or even mundane. Rather, hoping for something as politically freighted as “power” out of a chaotic biological experience aligns us with a long history of moralizing about birth — a history that has rarely given women the space to honestly encounter what happens to their own bodies. Religious dogma once saw childbirth as punishment, “natural” birth proponents see it as empowering. What’s a person who found birth to be profoundly amoral to do?

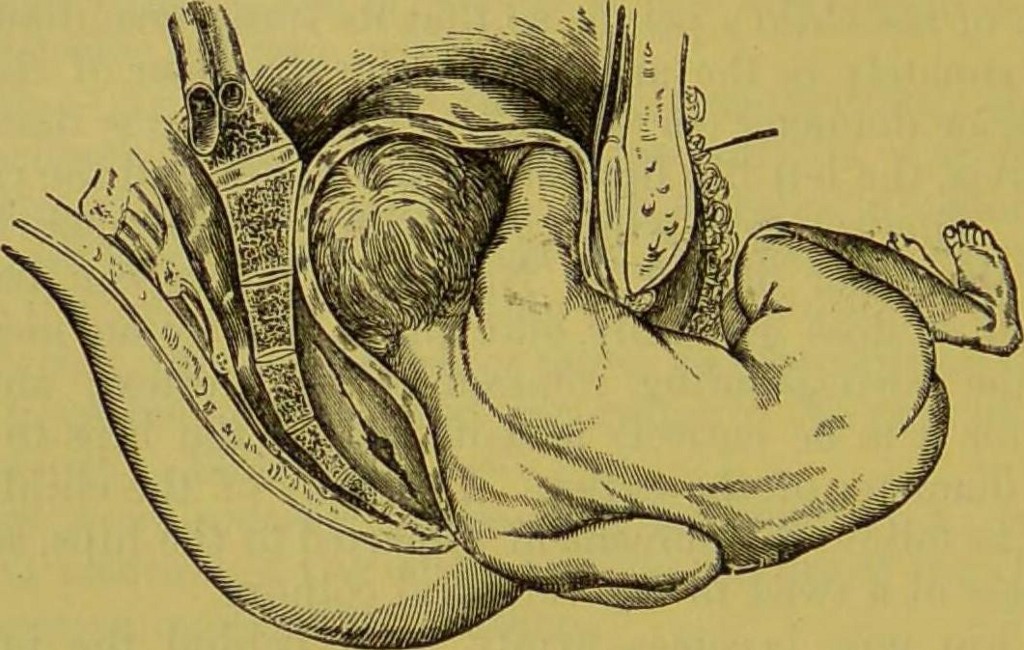

My two highly interventionist, medicalized births each ended in caesarean sections, life-threatening internal injury, and breastfeeding problems. Even more than the epidural, the c-section is the locus for some of the most intense birth moralizing of our era, which makes it that much more difficult to sift through the experience of having one. My c-sections were dehumanizing, disempowering, and yet completely illuminating. Personally, I prefer to hear, tell, and read stories about childbirth that give the lie to contemporary fantasies about empowerment. Birth is a monstrous thing, and it has no moral component. I side with the monsters, and have lived to tell their tales.

In 1639, pregnant for the sixteenth time, Anne Hutchinson miscarried and delivered a mass of tissue — today she’d likely be diagnosed with a molar pregnancy. Hutchinson had been excommunicated from the Church of Boston and expelled from the Massachusetts Bay Colony the year before for holding lay discussions of sermons in her home. Her large following threatened the church (and political) elders’ power, and it was a central aspect of what would come to be known as the Antinomian Controversy. Massachusetts Bay Colony Governor John Winthrop, who had questioned her about her lay preaching during the ministerial synod, kept tabs on Hutchinson even in exile.

When he heard about her miscarriage, he transcribed the description of it that he received from the physician who had examined Hutchinson into his journal: “I beheld … several lumps, every one of them greatly confused … without form … not much unlike the swims of some fish…The lumps were twenty-six or twenty-seven, distinct and not joined together;. . . six of them were as great as his fist, and one as great as two fists. . . . The globes were round things, included in the lumps, about the bigness of a small Indian bean.”

Winthrop continued, for years, to worry about the products of Hutchinson’s uterus. In 1644, he wrote a narrative account of the Antinomian Controversy and included detailed descriptions of Hutchinson’s and her supporter Mary Dyer’s miscarriages. Winthrop claimed that what came out of these women’s bodies was clearly a judgment from God, “as clearely as if [God] had pointed with his finger, in causing the two fomenting women in the time of the height of the Opinions to produce out of their wombs, as before they had out of their braines, such monstrous births as no Chronicle (I thinke) hardly ever recorded the like.”

Winthrop’s descriptions are only some among countless historical and contemporary instances in which a man in power attempts to discipline the reproducing woman’s body by marking it as animal and monstrous. He spun what was probably an emotionally wrenching, and certainly a mortally risky, outcome for these women as a divine judgment upon them.

But it’s worth sitting with Winthrop’s narration for a moment in spite of its undeniable misogyny. Winthrop is clearly terrified by these astonishing events. Hutchinson’s uterus produced something potentially inhuman. And though Winthrop tries very hard to arrange these lumps and globes into a story, he acknowledges that the issue of these women’s wombs is frighteningly outside of the realm of narration: “no Chronicle (I thinke) hardly ever recorded the like.”

How monstrous would it be for me to say that in this insight, I think he is right?

Winthrop inadvertently landed on an insight about the amoral nature of birth that centuries of women writers have considered in detail. I think a lot about the stories that historical women — fictional and real — have told us about childbearing. Mary Wollstonecraft writing to Godwin while in the labor (with Mary Shelley) that would kill her (“I have no doubt of seeing the animal today”), or Harriet Jacobs wishing the children she bore in slavery dead, or the climactic birth scene that Kate Chopin refuses to narrate in The Awakening. These are representations that reveal how superficial a concept empowerment can be when considered in the long intertwined social and biological histories of childbirth.

I think contemporary women (especially those who are keyed in to feminist discussions of birth) have a hard time listening to these kinds of stories: when birth is dangerous or wretched we think of it as gone “wrong” and we turn to thinkers like Gaskin to help us remember to trust the wisdom of our bodies. Bodies do have a sort of wisdom but it’s easy to lose track of how that wisdom is not moral. It’s the stories we tell about bodies that overlay them with moral values.

The theorist Della Pollack has written about how women’s narration of their experiences in childbirth “resist shame and silence . . . by throwing off narrative norms.” These moralizing norms shift across history; you can see them at work in stories where birth is “Eve’s curse” and in stories where birth is inconveniently primal in a stainless steel world. But what’s become increasingly clear to me after two wretched and disempowering experiences in parturition is that being empowered by birth has itself become a narrative norm — and that we need to push back against it.

The first time I gave birth, my body would not go into labor, despite leaking amniotic fluid for entirely too long, and days of trying to induce, both “naturally” (evening primrose oil, sex, castor oil) and “unnaturally” (pitocin). Never a single contraction, no building wave. Me and him, stuck there together, apparently unwilling to take a step into the story. Finally a c-section, massive hemorrhage, a husband removed from the operating room, and my own surprisingly pedestrian experience of near-death.

The second time around, because I was curious about labor (and scared of surgery again), I tried for a VBAC (vaginal birth after caesarean). After around sixty hours of labor (my curiosity, it was satisfied!), three hours of pushing, and a 103-degree fever, I finally wailed to my midwife, “I’m losing the plot!” She then applied, by way of a medical decision, a narrative structure to my experience of endlessness: two more pushes with assistance of suction before we would have to head into the operating room.

The willowy midwife and the petite female obstetrician who was on-call brought in a big broad-shouldered male doctor, a henchman really, toting a ventouse that looked like some kind of medieval torture device. He pushed a small rubber cup into my vagina, then torqued his wrist as he screwed it into place, suctioned onto the baby’s head. My uterus contracted, the big guy pulling hard and steadily while I bore down. I moaned, and there was the cacophony of encouragement at high volume around me until — POP! With an audible thwap, the little cup flew out of my vaginal canal, and blood splattered all over him. The room seemed to gasp, and my husband and I shrieked. Later we realized we both thought that the baby’s head had popped off. This idea was mostly ridiculous, but also: totally possible insofar as by that point I understood that anything was possible.

And so when the operation again encountered complications — adhesions between my uterus and bladder, causing a small tear in my bladder — I barely blinked. I wore a catheter for a full ten days after delivery, nursing my baby with a heavy bag of urine strapped to my leg. No chronicle exists that can make sense of this.

Perhaps it might be time to abandon altogether the idea of childbirth as a moral experience? Resisting the application of prospective and retrospective judgment, appraisal, and categories of “good” and “bad” altogether: can we imagine birth outside of these assignations? Is there a way for us to hold on to the monstrosity of childbirth? To look directly at Winthrop’s descriptions, refuse his hateful moralizing yet cradle those monstrous lumps?

My surgical births have provided me with a wonderfully warped view and I would not trade them. This is not because “all that matters is a healthy baby” (perhaps the most misogynistic phrase in all of postpartum language). But because as a parent, I feel like I have been afforded a vantage point that not everyone else has: I meet other parents in my neighborhood and have a hard time working up any of the same anxieties over picky eating or educational philosophies. “Who cares?! What does it matter?!” I want to lovingly shout at them. “We’ve all been wounded! Ripped apart from one another! It’s astonishing!”

Without even using my fingers to trace it, I still feel the scar low on my belly every day; my mind and body have reshaped themselves around this violent etching. After having my children in the way that I had them — in labor and parturition in extremis — I feel like one of those French feminists, all jouissance and self-shattering. Fuck empowerment! Children are little death machines, they rip through your body. They chew on you. They are animals. We are animals, left bloody and with vulnerable bellies sliced after a good fight.

Sarah Blackwood is editor and co-founder of Avidly and associate professor of English at Pace University.