Corgis shall follow me all the days of my life

Remembering Tasha Tudor’s illustrated ‘The Lord Is My Shepherd’

At some point in the last few years, my mother solemnly handed my childhood mementos over to me in a large archival box. Inside it I found, among my little drawings and ceramic hearts, a book version of the 23rd Psalm called The Lord is My Shepherd, illustrated by Tasha Tudor. I was expecting a child myself and scrambling to assemble edifying books to read to her. While I’m not particularly religious and couldn’t in any case picture intoning the 23rd Psalm to an infant, I remembered the book as an old friend from my childhood shelf, keeping company with a small number of Christian-themed books for children, like Tomie DePaola’s Parables of Jesus, and later, The Chronicles of Narnia. I wouldn’t baptize my daughter, and it was unlikely that I would take her to church, but I liked the idea of having a few tasteful religious texts around the place.

I was baptized and confirmed; I was taken to church and sent to choir. I have lost the habit of religion, though I am occasionally surprised by the residue it leaves on my life. I admire faithful people, believing still that religious practice is some mark of virtue. I experience the customary reverent shivers in cathedrals and mosques and other holy places, if they are beautiful. I pray when it is expeditious, in a manner that has more to do with fear and a compulsive streak than with God — secret mantras and gestures learned not from the Episcopal Church, but devised in the childhood dark or on scary airplanes.

I had the baby and forgot about the book for a while, dutifully holding board books with black and white pictures in front of her blurred eyes as I had been instructed by the child development treatises. By God, this five-day-old is going to get her proper start in life, I thought, until I realized she was a sleeping peanut and I could watch television for most of the day. Now the baby is eighteen months old and opinionated. She’s obsessed with books that have flaps and wheels and things that pop out, and she likes to abandon stories mid-way through to pick up another book we’ve read thirty times that week. But sometimes she takes a book from the shelf and pads over to me and smacks my knee to pull her onto my lap and we arrange the book and her sippy cup just so, and she leans back and nestles her head under my chin and drinks her milk and sits through the whole story.

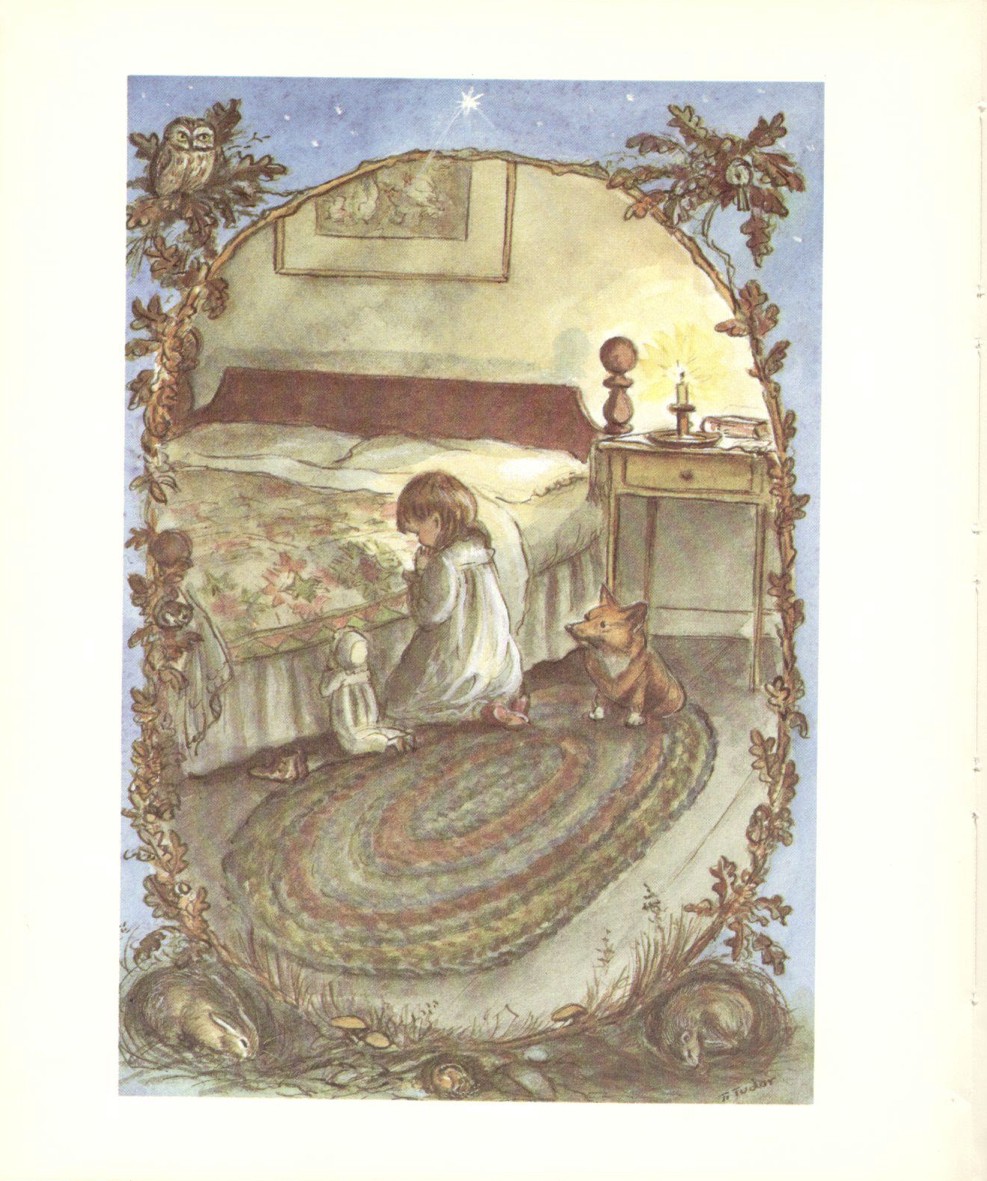

A few weeks ago, she padded over to me holding The Lord is My Shepherd. The book has that satisfying slightly loose spine of a book 30 years old or more, and firm, flexible, almost unctuous-feeling pages. “The Lord is my shepherd,” I read, feeling unaccountably embarrassed and weird, as though my child would judge me for reading to her about God. “Daggy,” she said, because the first illustration is a little girl watched over by a little corgi dog. “I shall not want,” I read. “Daggy,” the baby said: the little girl eats breakfast; a mother corgi gloats over her litter.

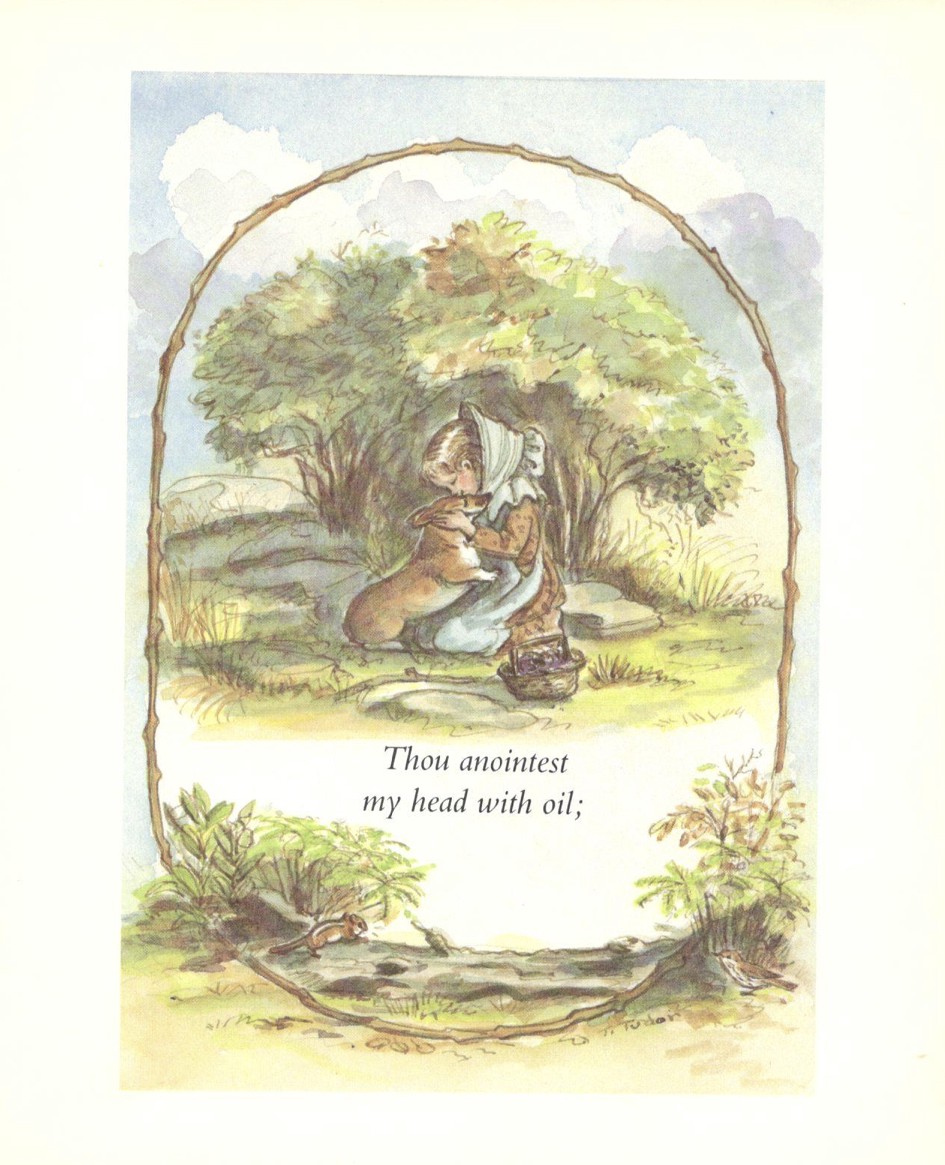

The 23rd Psalm as illustrated by Tasha Tudor is absolutely teeming with corgis. Corgis in green pastures; corgis beside the still waters; corgis in the shadow of death (represented by country graveyard and a circling hawk). The baby was delighted; but I had begun tearing up at verse 2, “He maketh me to lie down in green pastures” (corgis in a meadow, with cow). I was bawling by “Thou anointest my head with oil,” which shows the girl and the corgi sweetly embracing. “Daggy,” the baby said cheerily, while I blew my nose on my sleeve. At the last verse, “Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the Lord for ever,” the girl and her corgi sit on a hill at twilight, looking up at the stars.

The second time we read the book, a few weeks later, I wept again.

One summer weekday I wandered into the church I used to attend and sat down in a pew, where I promptly burst into tears; obviously, encounters with forgotten but familiar Christian places and rituals cause an upswell of subterranean sentiment in me. But there is something particularly affecting about Tasha Tudor’s imagining of the old psalm. The little girl lives in a bucolic setting with beehives and fresh bread and small packs of happy-looking livestock. She romps barefoot through the forest with no fear, delighting in streams and sunbeams. A corgi is her “mostly companion,” as her city-dwelling counterpart Eloise might say. The world is good and clean and sweet-smelling and self-sustaining. Even the evil is naturalistic and part of the order of things: a hawk with its eye on a field mouse. There is no climate change, no civil war, no refugee crisis, no electoral politics. The lord is with her indeed.

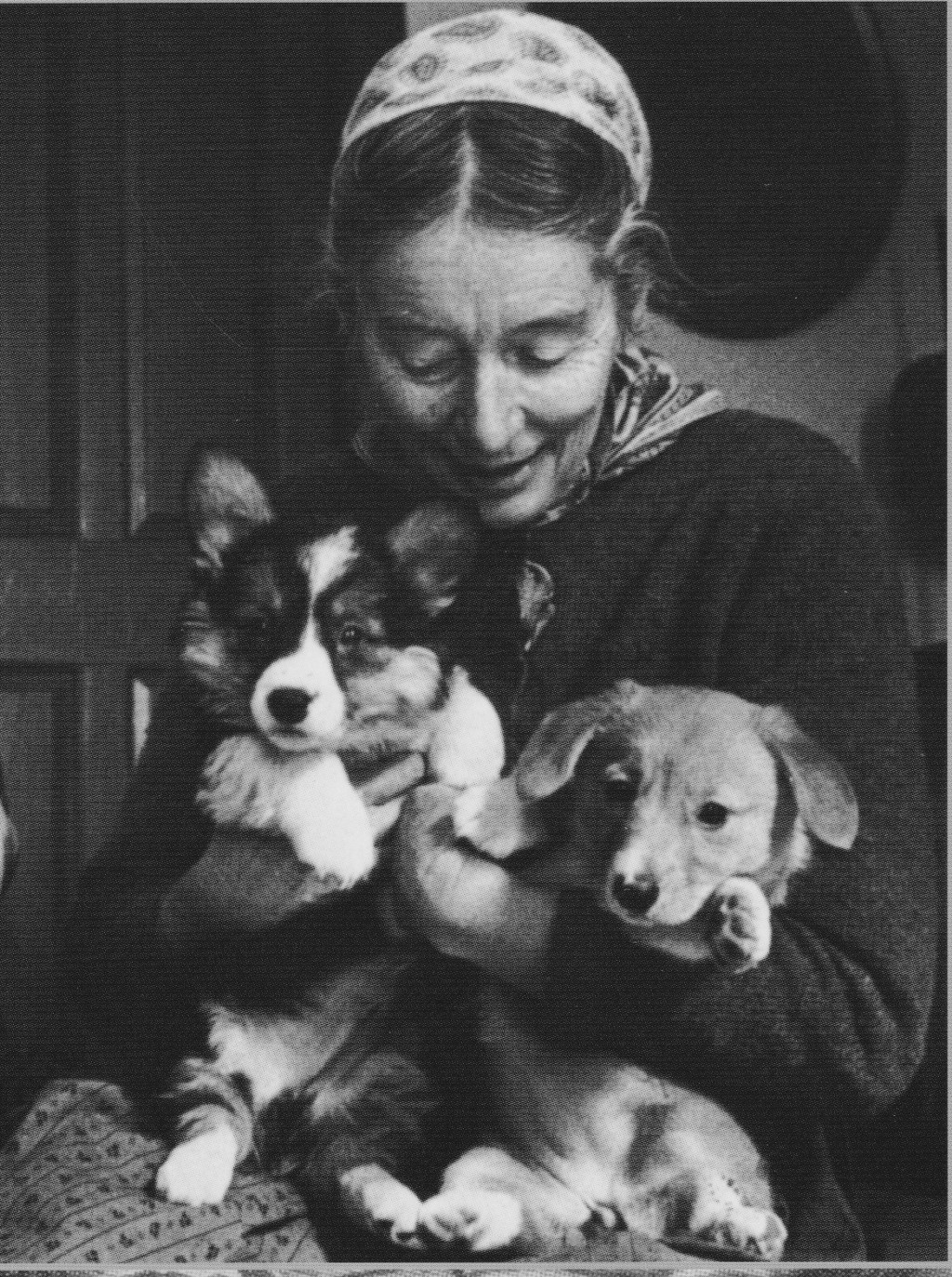

This was evidently the defining feature of Tudor’s work; her 2008 New York Times obituary describes a delightfully eccentric person who believed she was a reincarnated ship captain’s wife from the nineteenth century. Tudor, whose given name was Starling Burgess, raised her four children on a homestead where she went barefoot and made clothing from home-grown flax, accompanied by up to 14 corgis at a time. (She could “play the dulcimer and handle a gun” and “find a four-leaf clover within five minutes.”) The illustrations from the book are so powerful, maybe, because they were animated by her personal vision of the good life, a life she evidently tried very hard to live.

But Tudor also finds the opioid root of the psalm itself, which encapsulates all the comforts of religion without any of its complications, its challenges to serve. The 23rd Psalm is about sheep and a shepherd, if you parse the metaphor, and sheep have it pretty good, assuming their shepherd is nice and their pastures are green. They just have to be themselves and go where they’re led. The optimism of the psalm seems both necessary and cruel now, when the year, the decade, has been marked with human suffering, drowned children, things that should be our responsibility to fix. “Everything is going to be okay,” the psalm says; never is the impossibility — the hubris — of that promise more obvious than when you become a parent. But I was a child when I was religious and thus my religion is that of a child’s. So I let the book tell my uncomprehending baby that everything will be okay, and I try to believe it myself.

Lydia Kiesling is the editor of The Millions. Read more of her writing here.