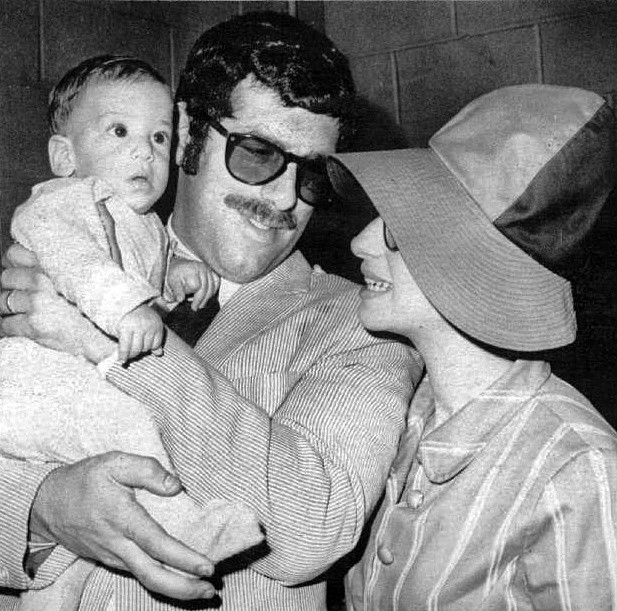

Elliott Gould and Barbra Streisand

Celebrities in love, overanalyzed by a newly married woman.

Elliott Gould and Barbra Streisand were in London, where she was in rehearsals for the English debut of “Funny Girl”; the musical had been a hit on Broadway, where Streisand had also played the lead. It was 1966, and they’d been married for three years. Her star was on the rise; his, which had seemed ascendant when they’d met in 1961, was now on a decidedly downward trajectory. They hadn’t had sex in weeks.

But on this particular night, as James Spada recounts in Streisand: Her Life, Gould was determined to “make love” to his wife. Streisand was anxious — not only about the musical, but also about the premiere of her second television special, Color Me Barbra — and Gould remembers having to “talk her down . . . all the way down through the whole encounter,” in order to get her to relax. (Gould’s description is, to contemporary ears, undeniably sinister; something close, perhaps, to coercion.) He used no contraception; Barbra got pregnant. “Barbra,” Spada notes, “seems not to have had any say in the decision.” It was precisely what Gould wanted: a baby was “the one thing . . . [he] could give her that she couldn’t get by herself, that no audience could give her, no amount of money could buy her, and no other man could give her. It was his way of reclaiming some of his self-respect.” When Gould found out from her doctor that his wife was expecting, he withheld the information from her until after the “Funny Girl” premiere.

Success — one partner’s achievements; the other’s lack thereof — can be a challenge in any relationship. In relationships between celebrities, that challenge may be more daunting because the markers of success — fame; choice parts in good films; money — are so visible. It wasn’t just that Elliott Gould, in 1966, was less successful than his wife: it was that everyone else knew it, too. “Her success was painful to me,” he told Playboy in 1970. “When we went out in public . . . it was devastating.” In England, the press dubbed him “Mr. Streisand.” In New York, when “Funny Girl” was on Broadway, Gould drove his wife home from the theater every night. When Streisand bought a “used Rolls-Royce,” Spada reports incredulously, Gould, “actually put on a chauffeur’s cap and drove her around town.”

The couple announced their separation in 1969. In 1970, Gould was nominated for an Oscar for Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice; he landed on the cover of Time magazine after starring as “Trapper” John McIntyre in M*A*S*H*, which was released later that same year. By 1971, Gould and Streisand had divorced.

Barbra Streisand and Elliott Gould met while working on the musical I Can Get it For You Wholesale, which premiered at the Shubert Theater on West Forty-fourth Street in 1962. Gould, who was twenty-three, played the lead: Harry Bogen, a conniving 1930s garment industry entrepreneur. Streisand, who was nineteen, played the spinsterish Miss Marmelstein, Bogen’s secretary — a small part originally written for a much older woman that was expanded and reconceived after Streisand was cast.

There are conflicting reports about their early flirtations. Spada indicates they did not become entangled until well into rehearsals. Barbra had just gotten a phone installed in her apartment (she was either subletting on West Eighteenth Street, or already in the one-bedroom on Third Avenue she would later share with Gould). At the end of a trying day, during which she’d fought with the director, she went around handing out her number “to anyone who would take” it; Gould called that same night. “You asked for somebody to call, so I called,” he told her. “I just wanted to say you were brilliant today. This is Elliott Gould.” In Hello, Gorgeous: Becoming Barbra Streisand, William J. Mann claims this phone call came right after Streisand’s audition, which she ended by singing out her newly acquired number. Gould’s line isn’t identical — “You said you wanted to get calls, so I called” — but his cocksure bluster is.

Gould’s directness was certainly part of the attraction. Streisand — a “gawky, skinny girl with . . . [a] distractingly large nose and crooked teeth and eyes that seemed to watch each other” — was insecure about her appearance. When she wasn’t onstage, her hair was often unwashed, her clothes grubby. And when she was, she cultivated a deliberately “kooky” (the word abounds in Mann’s biography; he seems to believe her early eccentricity was something of a put-on) appearance: at one of her first nightclub gigs she wore, a comedian who was also performing that night recalled to Spada, a “tiny high-heeled shoe in her hair because she liked the rhinestones in it.” The romance with Gould was not Streisand’s first, but it was, Mann asserts, the first in which her partner’s “interest was plainly evident, whereas, in the past, there had always been doubts.” And Gould knew it, too: he both “really dug her,” and felt he was likely “the first person” who really had.

Their early dates were suffused with a kind of thrifty magic: snowball fights, coffee ice cream in all-night diners, Pokerino in penny arcades. They didn’t try especially hard to be discreet, and by the time I Can Get It for You Wholesale moved to Philadelphia for previews, the rest of the cast was onto them: Streisand kept making her entrance from the wrong side of the stage — the one closer to Gould’s dressing room.

It was while they were in previews that Gould allegedly “surrendered” his virginity to Streisand. (Gould has also claimed, variously, that he first had sex at fourteen, with a girl “wearing a girdle who fell asleep on top of him,” and at nineteen, in a hotel room in Boston.) Their fights were fierce but fleeting — in Philadelphia, he once locked her, completely naked, out of his room; back in New York, he pulled a similar trick, though this time it was raining, and she was wearing clothes.

After the show opened on Broadway, Gould moved into Streisand’s apartment. The place was above a seafood restaurant and it smelled strongly of fish. It was also small and squalid — “the filthiest apartment I’ve ever seen,” according to a friend of Gould’s Spada quotes anonymously — and the couple had to share it with a stubborn rat they cheerfully named Oscar. But Gould was happy there, even if he was — by Mann’s account — not only Streisand’s boyfriend, but also her “chief cook and bottle-washer.” According to Spada, “He thought of himself and Barbra” — somewhat ominously — “as Hansel and Gretel, ensconced in an enchanted cottage.”

When did the enchantment break? Perhaps when I Can Get It for You Wholesale closed. Gould’s performance hadn’t attracted nearly as much attention as Streisand’s had. On the Monday morning after their last performance, Streisand began planning a national concert tour and finalizing the track list for her first studio album; Gould began collecting unemployment.

Streisand’s reputation has, in the fifty-plus years since her Broadway debut, both grown and calcified. Many who can recognize her face and speaking voice have never heard her sing. She is less a performer now than she is a diva — the word signaling power and (specifically female) difficulty, but not necessarily talent. This presents a challenge to biographers: the success that was dramatic, even shocking at the time, looks, from a distance, at once flat and inevitable.

But Streisand’s fame did not seem at all inevitable. Given her appearance, her perfectionist bent, the stubbornness that was half confidence, half insecurity, it seemed downright improbable, if not impossible. Perhaps it was the suddenness and the steepness of his girlfriend’s rise, rather than the simple fact of it, that Gould struggled to come to terms with. Perhaps it was how quickly the couple had gone from living in a one-bedroom apartment on Third Avenue with no hot water to a duplex on Central Park West whose master bedroom was tucked away in a tower, rather than the fact of the duplex itself.

Or perhaps it’s less complex. Gould may have merely been envious, the envy tinged with misogyny: when they’d met, he’d been the star. During their marriage, Gould started smoking a lot of pot and experimenting with hallucinogens. He went into analysis, explaining — apparently sincerely — that he was “just finding” himself. He developed a gambling problem; he wanted to experience some “hard-edged reality” and “winning or losing a bet” allowed him to.

Then again, it’s possible Gould’s unhappiness paralleled his marriage almost by coincidence; perhaps it was celebrity in the abstract — rather than Streisand’s in particular — that he couldn’t stomach. His wife had always known she wanted to be famous. As a teenaged coat check girl at a club called the Lion, Streisand had once snapped, “When I’m a big star on Broadway, you’ll still be just a bunch of drunken cackling hens,” to a group of rude patrons. But Gould had been “pushed,” as a child, “into lessons and auditions and recitals by his ambitious mother.” She’d even unilaterally decided to change her son’s last name — from “Goldstein” to “Gould” — before young Elliott’s first television appearance “because it sounded better.”

In 1971, after an Oscar nomination and a Time cover, Gould showed up on the set of A Glimpse of Tiger, a “comic fantasy” he was producing and set to star in as a con man. He was sporting “ a six-day growth of beard, chomping an old cigar butt and wearing a knee-length navy pea cot with an American flag where the belt should have been.” That day he certainly threatened, and may have actually hit, his director as well as his female costar, Kim Darby. Darby was, afterward, so nervous about being around Gould, that the studio hired armed guards to “calm her.” Production was shut down after four days. Two years later, when Robert Altman cast him in The Long Goodbye, Gould’s reputation was such that the studio forced him to submit to psychiatric tests.

“I think I have had certain problems which is that ego and vanity are toxic to me,” he told the Jewish Chronicle in 2010. “I became known before I knew who I was myself.” Streisand, he mused elsewhere, “became an icon, larger than life, and I had no understanding of why anybody would want to make themselves into something that isn’t real. Why would anybody want an identity that makes itself an illusion bigger than life?”

One could assume that Gould’s envy drove him and Streisand apart. But that seems scarcely more insightful than concluding that Streisand’s ambition was at fault — or noting that her affairs with Syndey Chaplin and Omar Sharif, her costars in “Funny Girl” on stage and screen, respectively, can’t have improved her marriage.

What seems closer to the truth is that Barbra Streisand knew what she wanted, and Elliott Gould didn’t. For a while, he tried, in the absence of an understanding of his own desires, to substitute hers for his own. Later, he imagined his desires might run parallel to hers. But the fame he achieved, he quickly discarded. These days, Streisand is married, apparently happily, to James Brolin. Elliott Gould seems to have gotten very into Judaism.

Miranda Popkey is a writer based in Cambridge, Massachusetts.