Until Next Season

On love and the NBA playoffs.

As the NBA playoffs come to an end, I look back on this time last year, when I couldn’t bear to watch them. The NBA, its bravado, and its most nihilistic aspects, were my ex-husband’s thing, or so I had fallen into thinking. We split up last spring, in what seemed like the most 1980s movie farce of a divorce. At the end of relationships, it’s hard to tell what belongs to whom, or how much of the wreckage is salvageable or worth taking with you. I’ve moved cities, changed radio stations mid-song, and avoided neighborhoods and bars that remind me of heartbreak. But the 2015–2016 Portland Trail Blazers, and their noble run in the post-season, played a significant role in getting over it, getting on with life, and learning to love again.

I’m from Dallas, Texas, where basketball didn’t count as a real sport until the late eighties. My mom’s East Dallas relatives are rabid Cowboys fans, dating back to the Cotton Bowl era. My Grandpa fashioning a “Cowboy Antenna” to the roof in 1966 to watch blacked out Cowboys games on TV. I have vivid memories of going to Tom Landry’s retirement parade, and the early-nineties Cowboys remain football’s platonic ideal to me. My father, who came to Dallas from Cuba in the early sixties, adored the Rangers, towing my sisters and me to games in Arlington stadium with fried chicken and Kool-Aid.

The Dallas Mavericks, on the other hand, were a new repackaging of goofy seventies ABA Basketball for a flashy eighties Dallas crowd. Their owner, Don Carter, bought the franchise as a gift for his wife, Linda, who had played ball in high school in Duncanville. In the early days of the Mavs, the team was outshined by its sister organization — the WBL’s Dallas Diamonds regularly outsold them at Reunion Area, and Nancy Lieberman’s basketball camps for girls are a Dallas institution.

All the most fervent basketball fans I knew were other women and girls. My Grandma had played basketball all her life. My aunts worked concessions at Reunion Arena, low key but committed fans, sources of player gossip, celebrity sightings, and detailed game recaps. And in that era, the Mavs provided schoolgirl crush fodder of the finest sort: A friend in elementary school wrote a fan letter to Detlef Schrempf and boasted about her autographed picture. Jason Kidd, the Mavs’ 1994 draft pick, instantly became a source of school-bus adoration.

I’d been with my ex since 2004, when we’d made out after a Halloween party. Halloween, or the opening night of the NBA season, was our de-facto anniversary. We had many great basketball moments together: watching the Suns and the Spurs in the mid-2000s in bed, watching Kevin Durant and Lamarcus Aldridge play for the Longhorns, watching my beloved Mavs take the finals in 2011.

But being with him made it hard to enjoy the sport in the way I always had. He scoffed at “rooting for a team” as a pedestrian idea. We moved cities, and his lack of interest in local sports cultures nearly negated the universalizing advantages of sports fandom. I wanted to be on a team, to be with someone to compare notes with, to challenge and validate each other’s assumptions and hypotheses. He wanted to silo himself, to pickle his ideas and opinions before sharing them with anyone.

I’d been married — and so singularly focused on trying to stay married — for so long that I’d forgotten what it was like to even contemplate romantic prospects. I opened a new Google spreadsheet and gave myself an assignment: list five men I would fuck. “Reasonable Prospects,” I called it. The first two were longtime unrequited crushes, hot guys I knew in real life. But I was lost after that. Maybe an athlete? Is that the purpose they served for women like me? Stand-ins as reminders that I was in fact a heterosexual? I often think that straight men get intimately interested with the bodies of athletes: in fantasy sports stats, in injuries, as a stand-in for intimate involvement with their own bodies.

I could only come up with one more entry: Robin Lopez, whom I had seen around the Pearl District. “He’s half-Cuban, like me, went to Stanford, probably smokes pot, probably wants to watch Star Trek”. I looked at his stats. His age: 27 to my 34, seemed perfectly respectful. Shortly after, Lopez, along with Lamarcus Aldridge, whom I’d followed since his Longhorn days, left the Trail Blazers.

I knew I wasn’t ready to enter a new relationship, but I knew I was ready to get laid. I downloaded Tinder, deleted it almost immediately. I got back on Tinder, and engaged in strange and stilted flirtation with dudes in a five-mile radius. I’d never online dated before, but the directness, the straightforward signaling of Tindering was refreshing. It was portion control for the serial monogamist.

When I first heard my current boyfriend talk about the 2000 Blazers postseason, I laughed. He’s younger than me, so our memories are mismatched: he was a seventh grader in Beaverton, I was a nineteen-year-old in Oklahoma. I’d watched that series with one of my first boyfriends, who seemed scandalously older at 24. Like many of the punk nerds and skater dudes I’d associated with, he held a secret shame for liking sports, which I thought was stupid. We watched the series in his dusty bedroom in his gross fourplex apartment in Oklahoma City, eating vegan BLTs and rooting for Rasheed Wallace and the Blazers, cursing at Kobe Bryant. The romance ended terribly, but I still look back on those games and realize how connected I’d felt, for the first time with someone outside my family, by cheering for a team.

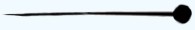

Shortly after the Blazers lost in game seven of the western conference playoffs and ended a postseason unseen since their Clyde Drexler/Bill Walton glory days, we broke up, I dropped out of college, and moved to Olympia, Washington. In the following years, I went back to Texas, then back to Seattle, for a PhD program I never finished, dropping off and picking up dudes and dalliances with sports teams. In Austin in the mid-aughts, I made friends with a bunch of girls in grad school who were obsessive Spurs fans, and we watched the playoffs in college bars and living rooms. My Vancouver friends gave into their birthright hockey obsession, and I watched the mild-mannered punk girls I knew in my twenties morph into shouting Canucks fans in their thirties.

By the time I found myself back in Portland in 2012, I realized that I had to make a commitment of some sorts to stay. I was supposed to finish a dissertation, but unsorted and unfinished business seemed about as useless to unpack as the Heath Ceramics wedding china in the basement of our rental house. I had some research funding from a hardware manufacturer, but was unmotivated to go find more.

My husband took a job at an ad agency, doing a surreal sort of over-the-top sports marketing for a sneaker company. He traveled constantly and on last-minute notice. When he wasn’t on a shoot somewhere or living out of a hotel in LA while doing endless rounds of post-production on multi-million dollar commercials that would sometimes never see the light of day, he was in the basement of the house we’d rented in Northeast Portland, watching League Pass. He’d flip through, game to game, all winter. I hated the chaos and lack of coherent narrative, but I hated those things in my life, too.

Portland grew on me, enough for me to not actively want to leave it, probably the best relationship indicator I’d come up with. I was lonely, isolated, overwhelmed with both the responsibilities of childcare and the nagging presence of postpartum depression. “It’s called a double depression,” my psychoanalyst told me.

I felt more alive when I worked in my yard or rode my bike around the city, and I realized that I wanted my daughter to grow up here, and I wanted my grownup life to be set against the backdrop of this idealistic city. Portland’s female archetypes: of Ramona Quimby, of Riot Grrrls, of cool strippers, female chefs, cargo bike riding moms, were those that I had desperately needed.

Last spring, around the time that my ex declared he was done, I was working on a contract research project, interviewing people about how they managed their passwords. (They do not, I can tell you, as a result of that study.) I laughed bitterly when I read about Gilbert Arenas, the wild, half-Cuban point guard — he was a character on the periphery of my marriage, like dozens of other NBA players. Arenas had smashed his children’s mother’s windows, and then the windows of his own car, filming it all, on the grounds that she had changed his Netflix password.

The 2015 playoffs came and went: I watched seconds of the games in bars before turning away. I caught myself crying, watching SportsCenter one night while working alone in my basement, at Stephen Curry and his precocious, curly-haired daughter, Riley — she looked like our daughter. I over-exercised and under-ate and lost the twenty pounds I’d gained since pregnancy. I worked like a dog, taking on a job in a big British agency doing global marketing and “service design” for the sneaker company. Recreational weed became legal in Oregon and I smoked a lot of it. I read all of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels.

My years as an advertising wife, and as a tech worker in what I called, affectionately, “The Athleisure Advertising Industrial Complex”, insulated me from the wider world of Portland’s sports fandom. I liked the Blazers, sure, I had since those 2000 playoffs, but I’d only gone to a handful of games in the three seasons before. But being single in Portland meant reckoning with the local interpretations and fraught masculinities of civilian sports fandom. “They get excited about American men’s soccer here,” my friend Kelsey groaned.

I had swiped left on any and all dudes on Tinder clutching soccer scarves and holding an extremely large axe in some Timbers Army party photos. All I knew of the Timbers were the roving bands of drunk men in matching green outfits, the cultish devotion of acquaintances. As luck would have it, I found myself dating one of them at the end of the summer.

The dude had grown up in Portland and loved the Blazers in their turn-of-the-millennium heyday, but that fell far behind his enthusiasm for the city’s major league soccer team, the Timbers. He took me with them to stand in the Timbers Army section, where the audience participation element is overwhelming but the view of the field is good. I feel that wonderful feeling of detaching from the mayhem, watching bodies on the field, that I’d felt only at football games in Texas.

As the season started and Portland turned dark and wet, I started to get attached to the Blazers in a way I hadn’t before. On the nights when my daughter was at her dad’s house, I would watch the Blazers on the local network while I ate dinner alone, marveling at the corny local TV ads. I met my friends at my neighborhood sports bar, where there’s a raffle during every Blazers game. When colleagues or neighbors said, “I don’t even know who’s on this year’s Blazers,” I resisted the urge to tell them to pay attention. I bought a red-and-black Portland toque, and chatted with old ladies at the grocery store about the new team. I developed a fond ritual in checking in on the score on the Blazers game after my daughter was in bed. I stayed up later than usual.

I fell in love with the 300 section, the upper ring of the Rose Garden, as a bastion of populist and accessible entertainment. It’s called the Moda Center, technically, since the Longshoreman’s union dental insurance company got rebranded and bought the naming rights. I bought ten-dollar tickets with a friend to see the Mavs play the Blazers. Wesley Matthews is back in a Mavs uniform, playing again after a long injury and crowd cheers. I texted with my Mom about Dirk. The Blazers lost in overtime, but Allen Crabbe shot 18 points.

On Black Friday, I got an email about a sale on Blazers tickets, and I gave myself a budget of about a hundred bucks, getting pairs of tickets for 5 games up in the 300s. I took my friend Cara to her first Blazers game, against the Kings. I took my friend Susan to one game, and we sat next to a friend of a friend and another couple they know. One night, I took my friend Rachel, and we looked up to see my old friend Beth and her wife, sitting on the floor, winning a Massage Envy gift certificate in a first quarter promotion.

I quizzed my boyfriend guardedly, “What do you even want out of this relationship?” a question I tried and failed to answer myself. But seeing life on local television every night and in a 1990s arena makes me consciously want some things. I rode back to my neighborhood on the MAX, surrounded by old couples in Blazers apparel from past decades, and it makes me unironically think of the internet vernacular “relationship goals”.

My daughter watches basketball with her dad, and recaps games in an adorable four year-old’s fashion. After All-Star weekend, she recapped the winning dunk for me. I can only assume he’s made an effort to make it all have some narrative she understands. Maybe she realizes what many adults do not, that sports are a safe topic of conversation and commonality, when fitting in in a new place, and even the most uncomfortable and uncharted situations. Maybe she realizes that loving something someone else clearly loves is an affectionate gesture.

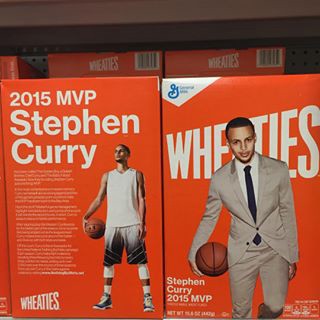

She saw Steph Curry’s Wheaties box in the aisle at the grocery store, and not only insisted I buy it, but refused any other Wheaties but the ones that come in the Steph Curry box. I bought generic Wheaties and put them in the Steph Curry box. “He’s the man around our house”, I tell her. It was hard for her to reconcile her love for Steph Curry with the fact that he does not play for the Blazers. As the season wound down, she told me, “I like Damian Lillard, but I’m sad. The Warriors are the best”.

In my basement, my boyfriend and I watched the Blazers lose valiantly once again to the Warriors in Game 5. “Being a Blazers fan teaches you how to lose gracefully to Californians”, he said.

“The season is over,” I said to him and smiled.

“I’ve been waiting for this season for a long time,” he said, “since 2000”.