The Family That Plays Cribbage Together

Complicated games for complicated people.

On family vacations, there always looms — especially during an election year — the threat of conflict. Last month, just a few days into a trip to California with my parents (divorced, acrimoniously), my uncle, two cousins, and my grandmother, I found myself in a hotel room, watching my relatives: voices were being raised; there was much furious gesticulation. They were arguing about the rules of cribbage. If ESPN commentary often devolves into “sports shouting,” this, I decided, was “cards yelling.”

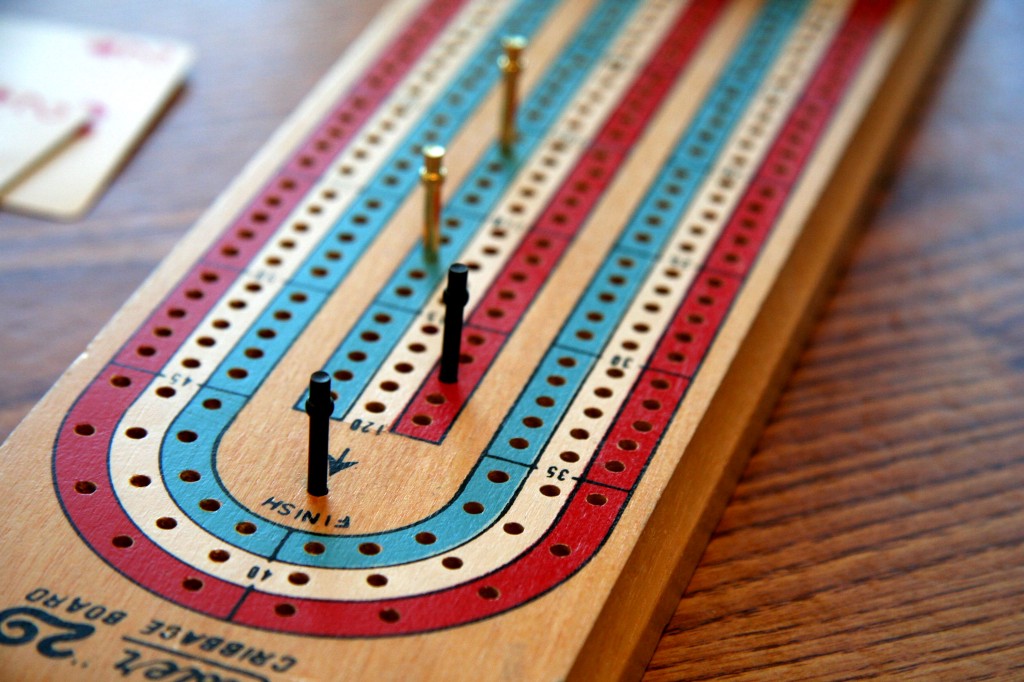

The most surprising fact I turned up when I began researching cribbage, an English card game (a board is recommended for scoring) that dates back to the 1600s, was the claim that it is “very popular in the United States.” Encyclopedia Britannica reports that ten million people play it in this country; one cannot, of course, rely solely on anecdotal evidence, but it bears mentioning that outside my own family, I have encountered exactly none of them.

Cribbage — whose complicated rules I will not summarize here; suffice it to say one tries, as in poker, to collect runs and pairs and flushes; cards that add up to fifteen are also good for two points — derives from an older game (no longer played) called Noddy. The game differs from Noddy in only one major respect: the presence of the “crib” — an extra hand whose points the dealer gets to count at the end of each round — hence, “cribbage.” “Noddy” was originally a synonym for “fool”; later it referred, in a gaming context, to a Jack of the same suit as the turn card. It is not — by a long shot — the silliest name ever given to an English “pub game.” (Cribbage remains the only game you can play in a British bar for money.) That award must go, in my opinion, to “Daddlums,” with “Devil Amongst the Tailors” coming in a close second — though really, it’s hard to choose a favorite.

Consensus has anointed the English poet Sir John Suckling as the inventor of Cribbage — or at least as its most successful promoter. (Though Suckling is commonly credited with developing the game in 1632, the Oxford English Dictionary gives the date of the word’s first appearance as 1630.) Cribbage aside, Suckling is a darkly appealing figure: “the greatest gamester both for bowling and cards, so that no shopkeeper would trust him for sixpence,” and a womanizer besides. He allegedly distributed packs of marked cards to “Gameing places around the countrey,” earning £20,000 (£4 million today) playing cribbage, with those same decks, for money — though this story may well be apocryphal. He claimed to have better luck when he dressed well; when he was on a losing streak, he would “make himselfe most glorious in apparell, and sayd that it exalted his spirits.” Suckling committed suicide at the age of thirty-two by drinking poison that “killed him miserably with vomiting,” either because he had “come to the bottome of his Found,” or because he feared the consequences stemming from his involvement in a plot to liberate the Earl of Stafford from the Tower of London.

I didn’t know about Suckling, or his rakish ways, when my grandfather taught me how to play cribbage at some point in my late childhood. My grandfather — technically step-grandfather: my father’s mother’s second husband — was a tall man, broad-shouldered, with thick hair so white I once asked him if he dyed it, and a luxurious mustache. He kept a black plastic comb in the breast pocket of his short-sleeved button-downs; he built the house he and my grandmother lived in; and he loved cribbage. He died when I was thirteen — I have some of his ashes in a Ziploc bag on the bookshelf next to my bed — and, after my grandmother died, too, five years later, we all fell out of the habit of playing. A great deal of the cards yelling was over rules: we’d forgotten the details of the game, and I kept having to consult Wikipedia.

One of the pleasures of enduring relationships — perhaps especially with people about whom you have complicated feelings, i.e., relatives — is the development, over time, of a secret language. Nicknames, verbal shortcuts that reference stories everyone’s heard three versions of: it means being known. For me, my father, and his brother, cribbage is one of the ways in which we acknowledge that we are family.

It helps that everything in cribbage has a ridiculous name. If you’re playing to a hundred and twenty-one points and lose by thirty or more, you’ve been “skunked.” To lose by sixty or more is to be “double skunked” — the ignominy of the defeat enhanced by the odiferous term. If you’re playing “cut-throat,” when another player undercounts his or her hand, you get to yell “muggins!” and take the extra points. If you have a Jack in your hand of the same suit as the turn card, you get one point “for his nob.” A hand with just two pair (four points total) is a “Morgan’s orchard”: it’s an old pun — two pears is a (very) small orchard, and Morgan is a stereotypically Welsh last name. A hand with no points at all is a “nineteen,” because the score is mathematically impossible to achieve.

There’s a neat way to tie all this up: “We fought about other things on that trip, too, of course,” I would acknowledge in that ending. “The cards yelling, at least, I’ll remember fondly.”

That is not a lie; but it is a gross oversimplification. At one point, for example, my father and I decided — on top of a mountain, after a two-and-a-half mile hike — to relitigate the details of the dispute that led to my mother winning primary custody of me when I was thirteen. Or take the cards yelling in the hotel room: my father refused to actually participate in the game; instead, he shouted advice as his brother tried to teach my mother and grandmother (actually my step-grandmother: my father’s father’s second wife) — who had never played before — the rules.

Then again, symbols function precisely because they are able to seamlessly subsume the messy details of the narratives from which they draw their power. On a queen-size mattress in a Doubletree in Claremont, California, three people unrelated by blood played a meaningless card game. Alternately: my uncle invited his stepmother and his ex-sister-in-law to participate in a family ritual, and my father, in his way, helped. That second version is the one that allows me, now, to look back on a sometimes-fraught vacation fondly.

Miranda Popkey is a writer based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Follow her on Twitter: @mmpopkey