My Dad Reads ‘Wuthering Heights’ For The First Time

My dad and I are enthusiasts. We are two punchy salespeople, and we would like to interest you in this book. It is Middlemarch, or All My Puny Sorrows, or A Brief History of Seven Killings, or the last thing we really liked. Please read it right now. You might as well, because we will not hush until you do. Just get it over with, and then come back and tell us that you loved it.

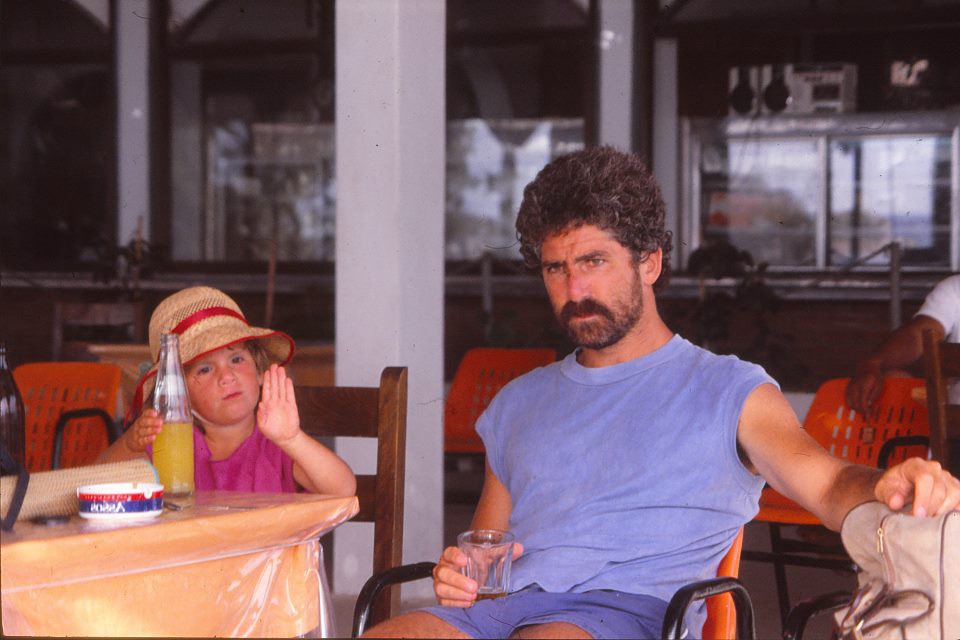

We are blind to the faults of the things that we love. My dad will not, for instance, hear a word against Bach. If you get into his car and start it after he has been driving around by himself, you will be immediately pinned to your seat by the wall of Bach coming out of the speakers. It’s Bach at levels far beyond what I presume was intended. Bach is for when you are at home, surely, and you are putting together your elegant supper, and your friend arrives and says Wow what’s this, and you say It’s the Goldberg Variations, man. The Goldberg Variations are for when you are a Count in the Saxon court, and you have sleeping problems, and so you get Bach to compose something to help you relax and ease the misery of your insomnia. Is Bach intended for driving to the beach with your daughter, and it’s so loud neither of you can hear a fucking thing, and she says, DAD THIS IS AWFUL I HATE IT, and then you scream the story of the Goldberg Variations’ origins over the distorted sound? N.O.

I’ve told him so many times that I hate it. He looks at me, startled. But it’s BACH, he says. Just LISTEN. I say that I don’t want to, and he pretends to understand, but really he doesn’t. It’s BACH.

He is similarly bewildered by slights against the books he adores. My dad is a great one for tirelessly recommending books about Shackleton, or Poor Old Captain Scott of the Antarctic, or Darwin, or Roger Casement. He is very persuasive, and, as a result, I have read fifteen more books about Captain Scott than I need to.

For a long time, these books were non-fiction only. My dad studied English at university (lectured by the apparently terrifying J.M. Coetzee), and assures me that he read heaps of novels when he was younger. At some point, though, he just stopped. Maybe he got a few duds in a row, or he read a book that was too sad, but at some point before I was born, he hardened his heart against fiction and turned exclusively to non-.

This happens sometimes, I think. Mostly to men. They begin to feel that there is something vaguely unsound about fiction. That it is charming, but will ultimately let you down, in the manner of a guest who chatters effusively at dinner but who did not bring any wine, and who ignores all the unattractive people at the table. That it could not teach you anything that wouldn’t be more effectively learned via a book about the Dyatlov Pass Incident.

He ditched fiction altogether, for about twenty-five years, and he was happy with this arrangement. Then, he put his back out — classic dad move. He was immobilized for weeks, and all he could do while he recovered was lie there and read. He burned through three books about Stalin, I was told, two books about George Mallory, one about the Bloomsbury group, two about what a monster Cecil John Rhodes was, and two about epidemics that went especially out of control. He read every piece of non-fiction his house had to offer, and then he ran out. He panicked, and my mom said Why don’t you read a book. He said that he was, and she said, A real book, I mean. A novel. Like what, he said. I don’t know, she said. Like this. She handed him Lolita.

It’s not that he loved Lolita, understand — he is a nice man, and a dad, and the whole exercise was ultimately too gross for him, but he could not deny its impact. Here is an excerpt from an email he sent me while he was reading it:

“I’m just taking a well deserved break from Lolita. It’s so intense that its making me agitated. I feel that I may not be able to carry on, even though I know I will.”

Lolita renewed his respect for fiction, but it did not make him fall in love. Middlemarch did that. I was visiting my parents for the weekend when he was about halfway through, and he walked around the house like a man in a trance. His eyes were all misty, and he kept raising his hands to his head. When I got back to Cape Town, there were emails waiting, with subject lines like “DOROTHEA”, and “Oh God, Lydgate”, and “I think Mary Garth is great.” It was all we spoke about for months.

He felt very strongly about Middlemarch, but he was not totally sure about Dorothea. He liked her fine, but he could not really commit. He thought that she had it too easy, overall. Dorothea knows little of suffering, or at least not the polar explorer kind of suffering that my dad reveres: cold, sad, starving to death, etc. Crying out for help and no one even notices, etc. The suffering of a friendless orphan, a trembling reed of a person.

Enter Jane Eyre.

Jane Eyre the novel, but also Jane Eyre the character, who my dad speaks about as if she is a real woman — the best woman to ever exist. Jane Eyre blew my dad’s mind, and Jane Eyre broke his heart. Subject line: JANE EYRE IS THE BEST. Subject line: I WISH I COULD HAVE BEEN BEST FRIENDS WITH CHARLOTTE BRONTË. Subject line: Didn’t you love the bit where she puts her foot down? Subject line: Didn’t you love the end?

The problem is, I didn’t. I didn’t really like any of it. Being the salesman that he is, it is hard for my dad to resign himself to the fact that I don’t love his favorite book ever. I just don’t. It’s too long, and too dense with stuff I can’t care about. I find Mr. Rochester creepy as the dickens. Most importantly, I have difficulties with Jane herself. I respect her, but I cannot warm to her. Something about her self-control, I think, her ability to make decisions and then turn them over in her mind, altering them if required. I like to make decisions and then shoot them out of a canon straight away, so it’s difficult for us to relate to each other.

Also, Jane isn’t too keen on laughter. She doesn’t seem like she would be very funny. The main laughter in the novel done by Bertha Mason, and her laughter is mirthless — tragic and evil, the laugh of a goblin. Laughter is also used to illustrate Jane’s exclusion: the woman is always hanging around in the shadows to watch other people gaily throw back their heads and bray into the faces of their splendid companions. She is skeptical of laughter, and knows that there are more important things in life. I am at a total loss to describe what those things might be.

Jane’s entire personality serves as a rebuke to mine. We would never be friends. She would find me flippant and too hell-bent on having fun, and I would find her rectitude awfully trying. She is so hardy and stoical and brave and independent! She never complains! She is thinking the most potent thoughts imaginable, every minute of the day. Jane Eyre is heavy, and extremely intense.

My dad, naturally, admires all this without qualification. He doesn’t find her weird or boring in any way; he just thinks she is magnificent — a woman to look up to. He once sent me an email with the subject line “Jane Eyre: I love her.” He likes her spirit, and her independence, and how she doesn’t let anyone push her around. He even thinks she’s funny. He read Jane Eyre twice in a row, and then he read Villette (subject line: AAAARGH BELGIUM). He read Wuthering Heights (subject line: What is Hindley’s problem?), he read Agnes Grey (and then, of course, he read twelve books about the Brontës, and has ordered several more), and he will read The Tenant of Wildfell Hall before the month is out. He is probably reading Wuthering Heights again as we speak.

Check out my dad, urging these books onto all of his friends, and phoning his daughter to tell her that he wishes he could have met Emily at least once. I ask him why he loves them so much, and he sighs happily. Think of them, he says, up at that awful old parsonage, churning this stuff out. Just think of how clever they were. I do think about it. I think about how the Brontë sisters’ response to poverty and privation was to write some of most beloved novels in the Western canon. Until well into my twenties, my response to adversity of any kind was to phone my dad, and to listen while he told me how to fix it.

This sounds bad, maybe, or pathetic. I don’t mean it to: I just grew up with a dad whose whole metier is looking out for people. He knows that I can teach, and write, and talk to pretty much anyone, and that I am trying my best. He is also aware, however, that I probably shouldn’t be allowed behind the wheel of a car, that I frequently forget my own address, that I cannot tell left from right unless I hold up my one hand to spell the letter L and even then it doesn’t always work, that I get lost every single day, that I can break a phone charger just by looking at it. He recognizes all this, accepts it, and, from when I was a very little kid, has tried to make the world an easier place for me. He has always been on my side.

Jane Eyre grew up scared and alone, with no one on her side and no one to phone and say Help, please. She is serious, a little anvil of a person, because her world made her like that. This is perhaps part of the reason for my dad’s deeply respectful crush on her. He is pained by suffering, and has worked all his life to alleviate it where he can, and he knows what it means to be good when the world is so bad. He loves Jane Eyre because of her resilience, but he wishes it hadn’t been so hard for her. He knows that she doesn’t need protecting — she is way too tough for that. He just wants to be on her side.