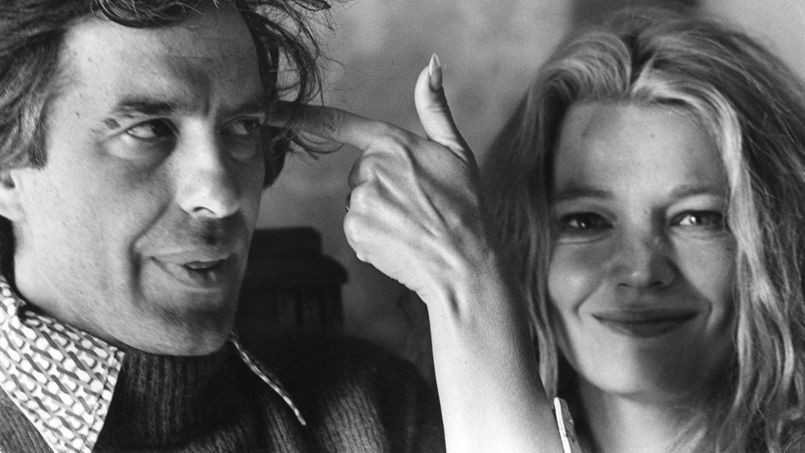

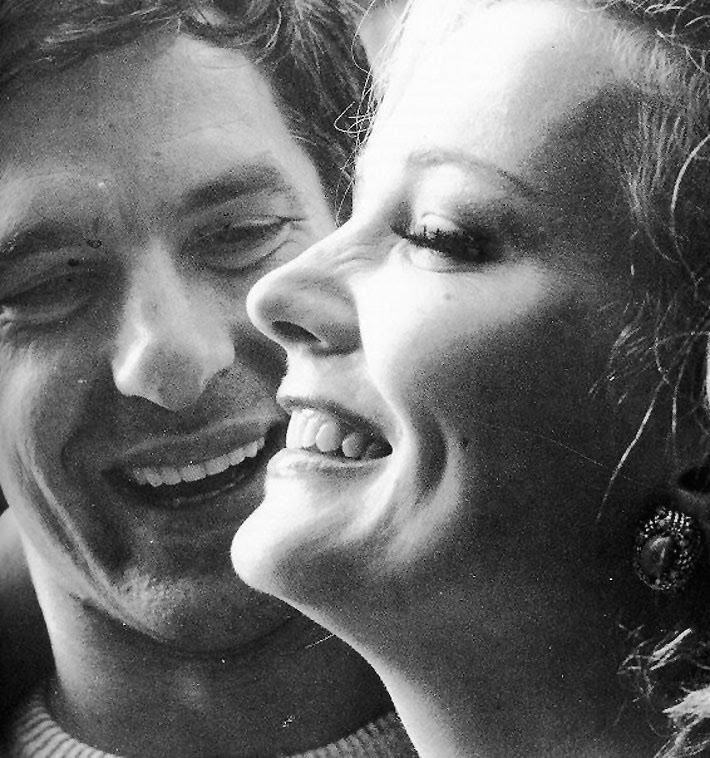

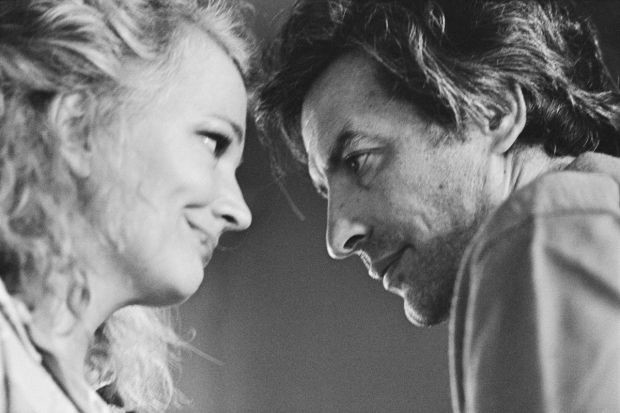

John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands

He put his films first; she made sacrifices.

Half an hour into director John Cassavetes’s sixth film, 1971’s Minnie and Moskowitz, Minnie, played by Cassavetes’s wife and frequent collaborator, Gena Rowlands, comes home after an evening with her friend Florence. She spends a few tipsy moments outside her apartment trying to figure out how much to pay her cab driver; she sings “When I Fall in Love” to herself as she stumbles inside; she chats with Florence over the phone for a moment. “Got home fine. Feel fine,” she reassures her friend. “Okay darling, I’ll see you tomorrow.” The camera cuts and through a doorway the viewer sees a man putting a suit jacket on. It’s Cassavetes. He takes a slug of beer and ambles into the living room. Minnie backs up. The man advances. And then he hits her: once, twice, five times. She’s on the floor at the end of it. “I don’t want you lying to me about being drunk, I don’t want you lying to me about ‘Darling,’ understand me?” he growls.

Cassavetes could be manipulative — even cruel — as a director, in order to elicit truthful performances. Case in point: he hadn’t told his wife in advance that he’d be playing the part of her paramour, Jim. “As time went on,” Rowlands reported, “I became more and more upset. I like to know who I’m working with.” As Ray Carney tells the story in his Cassavetes on Cassavetes, Rowlands was “floored” when her husband told her “just before the scene was about to be filmed” that he’d be playing opposite her. When he hit her, as the camera rolled, “the crew sprang to Rowlands’s aid, imagining she really had been attacked by Cassavetes, and Rowlands, to retaliate for Cassavetes’s refusal to tell her in advance that he was playing the part, pretended she had really been hurt.”

The anecdote — Cassavetes’s ruthlessness and his fondness for extremes (why did the crew think he’d actually hit her, anyway?); Rowlands’s cool seizing of an opportunity for revenge — is telling. It’s a pint-size portrait of their relationship, which was apparently loving, artistically fruitful, but also undeniably tumultuous: a decades-long battle neither ever tired of.

John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands starting dating in December 1953. Cassavetes, the son of a Greek immigrant, was small (five foot seven — he would lie about his height throughout his career) and energetic to the point of mania; Rowlands, the daughter of a Wisconsin state senator, was blonde with elegant manners. They were both driven, aspiring actors who hadn’t yet met with much success. Cassavetes tells a story of love at first sight — “I turned to a friend and said: “That’s the girl I’m going to marry” — but Rowlands wasn’t so sure. “The one thing I knew,” Rowlands told The Hollywood Reporter last year, “was I didn’t want to fall in love, I didn’t want to get married and I didn’t want to have children.” Four months later, in March of 1954, they were wed at the Little Church Around the Corner in downtown Manhattan. Cassavetes was twenty-four, Rowlands twenty-three. They were together for the next thirty-five years.

In Cassavetes on Cassavetes, the actor, writer, and director emphasizes to Carney how dissimilar he and his wife were. “We agree in taste on absolutely nothing,” he insists. “She thinks so totally opposite to anything I could ever conceive.” On this point at least, they were in agreement. “John and I probably disagree on just about everything in the world,” Rowlands told People in 1984. “That’s what marriage is all about. If you think a marriage isn’t going to be like that, you’ve got trouble.”

Carney attributes these disagreements in part to differences in upbringing and temperament. “She had grown up in the country and was from a financially comfortable setting,” he writes. “She was artistic and from a ‘musical background’ . . . He was the fast-talking street-smart city boy. Rowlands was socially smooth and refined; Cassavetes rough-hewn, impulsive, passionate and driven. She cared what people thought; he didn’t. She was cool, poised, charming; he was half-crazy, hot-blooded and Mediterranean.”

On set, his “half-crazy” side sometimes manifested as frat boy humor. While shooting 1970’s Husbands, Carney reports, Cassavetes would “walk past the actors ‘with a banana in his butt’ while filming was going on to change the mood.” Other times, attempting to elicit authentic, unpracticed emotional performances, he would resort to abuse. Lynn Carlin, one of the leads in Faces, was not a professional actress. (Cassavetes often employed amateurs.) “To create a feeling of desolation,” Carney writes, “just seconds before the start of one take, Cassavetes suddenly slapped [Carlin] across the face, then shouted: ‘Don’t cry! Don’t you dare cry!’”

But if Cassavetes’s volatility caused friction at work, it was also, perhaps, at the root of what seems to have been a deep, long-lasting bond with his wife. Rowlands was, Carney notes, “in her way, as strong-willed as” her husband. Cassavetes had “finally met his match.” The strength of her will is obvious in her on-camera performances — especially when Cassavetes is directing. As an actress, Rowlands is fierce, expressive, and physically nimble. (With a few anxious hand gestures, she turns her character’s daily wait for her children’s school bus in A Woman Under the Influence, into a high-stakes drama fraught with potential disaster.) She played the lead in six of her husband’s films, earning two Oscar nominations. The parts Cassavetes wrote for her were undeniably the meatiest, most complex of her career — a fact that, unfortunately, has made it more difficult to appreciate Rowlands’s professional success without invoking her personal life.

Money was always a problem. Cassavetes’s insistence on retaining final cut and his penchant for publicly maligning studio heads meant he was forced to self-finance many of his movies. (The fact that he largely shunned contrivances like plot — in his films, the action is halting, uncertain, driven by extravagant emotional outbursts, the rhythms of everyday life, and the slow evolution of relationships — probably didn’t help either.) During the making of Shadows, Cassavetes’s first film, they were “badly in debt.” Rowlands was seven months pregnant with their first child and they “owed the milkman … over $1,000.” Finally, Cassavetes “took the last $300 of her baby money” — the funds they’d set aside for hospital bills. “I’ll do it myself,” the director promised his wife, referring to the delivery. “Don’t worry about it.” “You won’t be here,” Rowlands retorted, “you’ll be shooting.”

So was Cassavetes’s obsession with his work. A few days after the child was born, Cassavetes began shooting a television series, Johnny Staccato, about a jazz pianist who solves crimes. (He’d taken the role purely for the paycheck.) When Rowlands flew to California to join her husband a few weeks later (they’d been living in New York), he seemed to have forgotten all about their newborn son. At Cassavetes’s office, as Carney reports, the couple exchanged “a little chitchat,” before Rowlands “impatiently inquired, ‘Aren’t you going to ask about the baby?!’ ‘What baby?’ Cassavetes replied.” Cassavetes would later speak of his regret at having “doubled-crossed” his wife. “I don’t mean that I’ve plotted it out and planned it out,” he explained, “but I’ve done things that have been a double cross. Working late at night. Working hard. … Being in love with other things.” Family, Carney makes clear, “almost always … took second place to his work.”

And yet they stayed together. “I don’t like sex in groups,” Cassavetes told Playboy, “and I believe in — and practice — fidelity in marriage.” (Though in a separate interview, he claimed that “if you’re a married man you have the right to get drunk, screw around and go to the whorehouse.”) There are no lurid accounts of drunken brawls, even though Cassavetes was certainly an alcoholic; cirrhosis of the liver contributed to his death, at the age of fifty-nine, in 1989.

Carney — who, it should be noted, is currently feuding with Rowlands over, among other things, what he perceives as her attempts, since her husband’s death, to sanitize Cassavetes’s legacy — suggests that their operatic fights were more serious than either let on. But his hints — about Cassavetes’s “unbelievable bouts of binge drinking, gambling, and womanizing in his time away from home”; about how common it was for “one or the other to temporarily ‘move out’ or run off to a hotel”; about the trouble Cassavetes would get into on his “boys’ nights out” — perhaps deliberately, lack specificity. It would be easy, even in the absence of more damning anecdotal evidence, to cast Rowlands as the long-suffering wife, stuck at home with three kids while Cassavetes pulled all-nighters in the editing room, or got drunk with fellow actor Seymour Cassel. Rowlands has never said anything in public that indicates she regrets the sacrifices that she made for her husband — or even that she believes them to be sacrifices.

It’s a truism that any marriage is, to outsiders, ultimately mysterious. And if, today, paparazzi shots of stars on vacation can create the illusion that we might be granted access to the private truths of a celebrity relationship, the Rowlands-Cassavetes union, troubled but enduing, reveals these truths to be definitively inaccessible. We can know only that it worked for them — or maybe even less; that, whether it worked or not, they decided not to divorce.

The clues Cassavetes himself left are all contradictory. “I always feel that when someone says ‘I love you,’ they really mean ‘I hate you,’” he once said. Also, “my idea of a love story is when two people get together and go through so much turmoil and so much pain just loving one another. I don’t know what anybody else feels, but that’s the way I’ve always known love to be.” But he also said, “Gena has been a miracle; my children have been miracles. Finding tears coming into my eyes during stupid conversations is a miracle. And after so much of my life has been difficult, repellent and a turnoff, I find that still being able to love is a miracle.” I cut the first sentence from this quote; Cassavetes mentions first, in his list of miracles, films.

Miranda Popkey is a writer based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Follow her on twitter: @mmpopkey