Created in Her Image

The conservative politics of Joan Didion

“I tell you this not as aimless revelation but because I want you to know, as you read me, precisely who I am and where I am and what is on my mind. I want you to understand exactly what you are getting.” —In the Islands

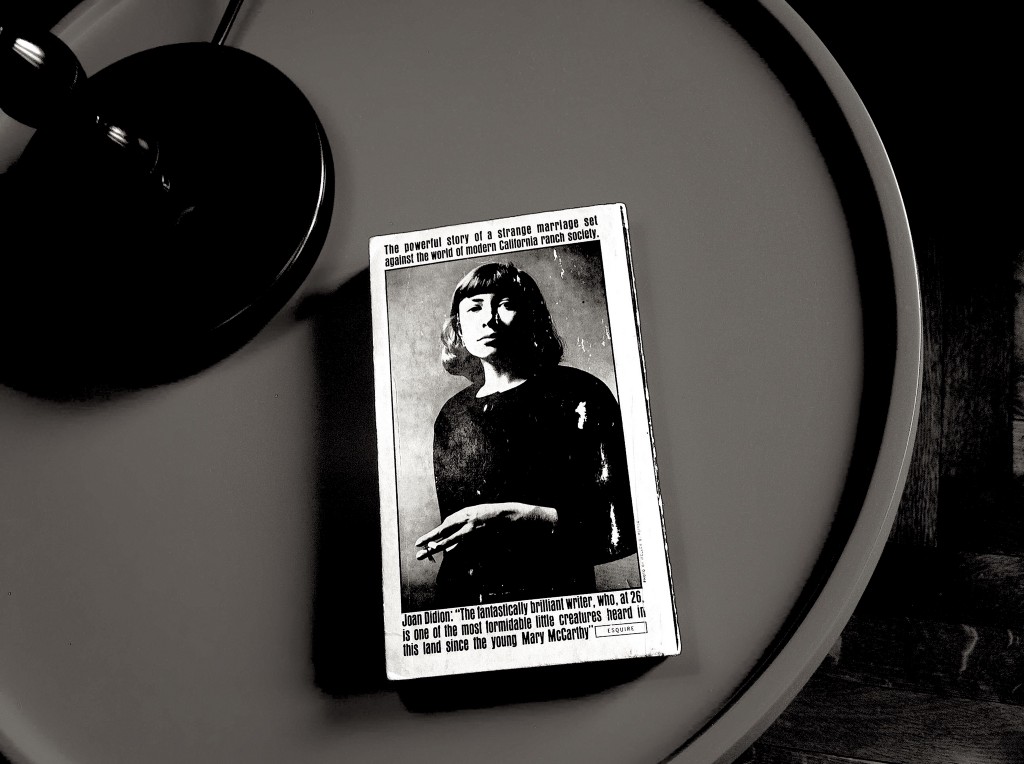

We live in a kind of renaissance of Joan Didion simulacra, an era in which Vogue runs her famous packing list as a slideshow of items for sale, and Olympia Le-Tan sells clutches with Didion’s book covers hand-stitched onto them. Young, fashionable, progressive people love her, a fact that has been well observed (and lamented by the hipsters who got there first). Beloved as she is by the progressives of the day, Didion began her career as a staunch conservative.

The case could be made that nothing has shifted in Joan Didion’s politics, but that politics has shifted around Joan Didion. From the eye of the storm, she chronicled the churning tornado of American culture in the 1960s and 70s. Her readers often assume, especially with the benefit of hindsight, that Didion supported the radical politics she so often covered. Of her reporting in the Haight Ashbury, Louis Menand writes, “She blended into the scene; she internalized its confusions.”

After penning dozens of essays on American politics, she writes, “I was asked with somewhat puzzling frequency about my own politics…as if they were eccentric, opaque, somehow unreadable. They are not. They are the logical product of a childhood largely spent among conservative California Republicans…in a post-war boom economy.”

Notice she doesn’t say “I am/was a Republican,” because that wouldn’t be honest. Instead, Didion talks about what gave shape to her political personality, which was really her entire personality. She grew up in a time “before the meaning of ‘conservative’ changed,” she writes; once it did, she became the first member of her family to register as a Democrat.

Before that, though, Didion tells us exactly what “conservative” used to mean: “The people with whom I grew up were interested in low taxes, a balanced budget, and a limited government. They believed above all that a limited government had no business tinkering with the private or cultural life of its citizens.”

Didon’s conservatism was both a cultural critique and a ticket to a seat at the table in journalism at a time when to be progressive was not to be taken very seriously. The advent of New Journalism, in which the writer used a narrative thread to tie a true story together and of which Didion would become an emblem, was still on the horizon in the early 1960s. To be a serious journalist at the time was, more often than not, to be conservative: Men like Forrest Davis, William F. Buckley at the National Review, and Vermont C. Royster at the Wall Street Journal were setting the tone. A woman had to be able to play by their rules if she wanted to join them — and so, for a little while, Didion did.

Once Republicans jumped ship on Goldwater for the likes of Ronald Reagan, Didion was ready to leave her party behind. Of being the first person in her family to register as a Democrat, Didion recalls, “That this did not involve taking a markedly different view on any issue was a novel discovery, and one that led me to view ‘America’s two-party system’ with — and this was my real introduction to American politics — a somewhat doubtful eye.”

The more Didion observed, especially during her travels in Central America, the more sympathy she displayed for radical causes. “Didion’s transformation as a writer did not involve a conversion to the counterculture or to the New Left,” Louis Menand wrote in the New Yorker. “What changed was her understanding of where dropouts come from, of why people turn into runaways and acidheads and members of the Symbionese Liberation Army…” In other words, it was her focus on people on the margin of societies that prompted Didion’s leftward turn. She told stories, and those stories influence her politics.

Didion rarely gives away her policy positions, but a close reading of her dozens of dozens of New York Review of Books essays reward attention. If you want to know Didion’s take on the machinations of the Religious Right, read her essay “God’s Country,” specifically the part where she talks about the sectarian nature of “faith-based” organizations in the US: “’Faith-based’…is a phrase with special meaning, a code phrase, employed to suggest that certain worthy organizations have been prevented from receiving government funding solely by virtue of their religious affiliation.” In the same essay, Didion refers to “’crisis pregnancy centers’” in quotation marks. She tells the attentive reader everything she needs to know, but in semaphore and whispers rather than bold, tweetable quotes.

In recent years, “conservative” has come to mean conserving the pillars of American nostalgia. We want the nuclear family preserved at all costs, manicured lawns in the middle of a drought, white picket fences (or border walls). We want to believe that idealism is the source of our national strength rather than one of its greatest polarizing forces. “Fiction is in most ways hostile to ideology,” Didion wrote in a 1972 essay on the women’s movement for the New York Times.

In other words, a good story necessarily includes ambiguity, especially in relation to the past. “Make America Great Again,” as many have pointed out, is a promise for a specific audience for whom America was great in the first place: Mostly white, mostly male. “There is a sense in which the whole idea of America is that it doesn’t have anything to do with the past,” Didion told the Harvard Crimson in 2001.

Didion is puzzled by the past. Her 2003 essay collection Where I Was From is a 240-page reckoning with the past, both hers and California’s. Nostalgia and sentimentality can blind a person, and this is the true manner in which Didion is a conservative: her “Cassandra dreams for American culture,” as Nathan Heller writes in Vogue, portend doom if we fail to heed them, if we fall prey to the promise of victory in progress.

Her obsession with the past had everything to do with her relationship to California, too, as a place she sought to distance herself from even as she was obsessed with it, then returned to for decades with her husband. The myth of California is that it is the place where the past goes to disappear, where time exists only at the present moment and every moment is better than the last. This is the “vacuum” Didion wrote about in her book of reckoning with the reality of California, Where I Was From.

Where I Was From is a long critique of the American ideal of progress, de-romanticizing the pioneers and their plight. Didion’s Gold Rush-era relatives buried their dead children as they made the trek westward, including an unnamed baby girl and a two-year-old boy, Tom, who had a fever and no hope of finding a doctor in time. They found a small trunk to bury him in. As they kept going, they carried seeds with them from the gardens they had kept at home. “The past could be jettisoned, children buried and parents left behind, but seeds got carried,” Didion wrote. What kind of “progress” leaves 2 year-olds dead in its wake but assures the survival of beans and squash?

Social accountability is at the heart of many of Didion’s early essays, from the title essay of Slouching to the story of Grace Strasser-Mendana in A Book of Common Prayer. The primacy of individual accountability is one of the last threads of connection Didion shares with the conservative movement; but even here, she has never discounted the importance of social systems. “In 1964, in accord with [conservative] interests and beliefs, I voted, ardently, for Barry Goldwater,” Didion wrote. “Had Goldwater remained the same age and continued running, I would have voted for him in every election thereafter.” It was Didion who remained the same and conservatism that changed.

Ironically, Goldwater is the man charged with sparking the modern conservative movement. He was soundly routed in 1964 by Lyndon B. Johnson, who won with 61% of the popular vote. L.B.J. was easily able to paint Goldwater as an extremist. (Goldwater famously said “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice.”) He supported the same bullet points in Didion’s introduction to Political Fictions — limited government, a “reasonable” budget, the primacy of states’ rights.

But his other positions were also far more right wing: He was against the Civil Rights Act and virulently anti-Communist. He was a hawk who insisted on “total victory” in American foreign policy. His campaign slogan was an inarticulate mess: “In Your Heart You Know He’s Right.” The Johnson campaign responded not only with their famous daisy ad but a slogan of their own: “In Your Guts You Know He’s Nuts.”

What exactly Didion admired in Goldwater is lost to the ages. She is certainly not going to speak about it, now that she’s all but hung up her shingle. And who can blame her? There are other things to worry about — grocery lists to write, newspapers to read. From her apartment on East 71st Street, the world must look very different now than it did in 1964.

Joan Didion is a cipher for anyone who reads her, but especially for the progressive young women who’ve found her in recent years. In that sense, Didion is not so unlike another “Goldwater Girl” whose politics shifted as the GOP shifted away from its laissez-faire roots. Hillary Clinton, influenced by her father’s conservatism, noted the party’s shift after the 1960s in an interview with NPR. Her reflection on the process sounds very much like what Didion might say, if she had anything more to add: “I don’t recognize this new brand of Republicanism that is afoot now, which I consider to be very reactionary, not conservative in many respects. I am very proud that I was a Goldwater girl.”

Laura Turner is a writer in San Francisco.