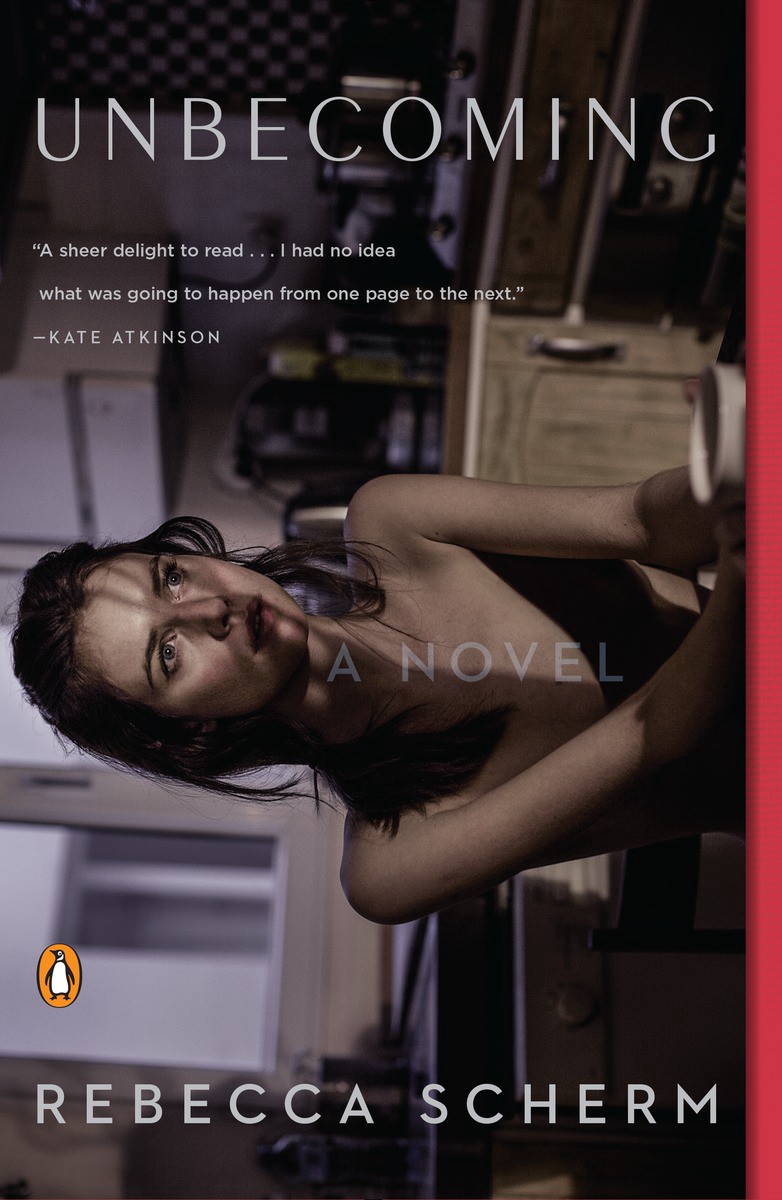

An Interview With Rebecca Scherm, Author of ‘Unbecoming’

by The Hairpin Sponsors

Brought to you by Penguin Random House.

An interview with Rebecca Scherm, author of the “startlingly inventive” (The New York Times Book Review) debut novel of psychological suspense, UNBECOMING — now in paperback.

There’s a lot of fascinating information in this book about the art and antiques worlds. What kind of research did you do to make this setting feel so genuine?

When I used to visit my grandparents in the summer, my grandmother and I spent a lot of long, hot Florida afternoons watching Antiques Roadshow. I loved the small suspense of it: the tension between the objects, both the obviously beautiful and the homely, and their owners, and then the big reveal of “market value.” When I was a bit older, in New York, I was making my own art (unlike Riley, I was all ideas, lousy execution) and rebelling against the ideas about history and craftsmanship that I’d learned growing up, when my family never missed an opportunity to tour a historic home. But soon enough, I became more interested in ideas about art — “worth,” intention, influence, ownership, taste — than I was in making art myself.

I did all kinds of nutty research for this book. On one memorably embarrassing occasion, I went to a gem dealer in the diamond district, trying to learn and sound knowledgeable at the same time. I bought a seven-dollar ametrine to thank him for his trouble, and then I had to pay the last two dollars in change. Not my smoothest game.

Every object in this book is something real that I found for sale somewhere. Some of them I visited in person, and they surprised me: the first time I saw James Mont pieces in real life, at Todd Merrill’s store in New York, the metallic finishes seemed cool, even icy to me, where I’d always imagined them to glow with a kind of heat. Always, I sought out objects that had some kind of contradiction, like the hideous pink diamond watch or the lumpy pottery. And I found that when Grace wasn’t moved by the object, she had no trouble stealing it.

Forgery vs. authenticity is questioned in this novel, both in terms of artifacts and personalities. Why explore this dichotomy?

Several years ago, I read a biography of the art forger Elmyr de Hory, who argued that if his Picassos were as good as Picasso’s, what was the difference? That biography was written by Clifford Irving, who was himself a fraud. But the funny thing is that de Hory’s notoriety has given his forgeries value in their own right.

“What interests me is the foggy sea between true and false. We’re confronted all the time with half-truths, with moments of doubt where we make an unconscious choice to see or not see the truth, with performances that have subsumed the actor. If you’ve ever talked yourself into or out of something too effectively, you’ve performed your way to a new truth. Grace’s life is made of these performances, and her work restoring decorative arts seems to her like a real penance, even if it seems to others — Hanna, for example — like a kind of approved fakery, a tacit agreement to pretend that mistakes can be truly erased, buffed out and shined over.

As I wrote, these roads — truths and lies, originals and frauds and restorations, inner and outer selves — kept intersecting unexpectedly. I’d be writing about James Mont and find myself writing about Grace’s id, or Grace would fantasize about art theft while refusing to confront her jealousy of Riley’s position in his family. The Heather Tallchief story is a perfect example, because the way Grace aligns herself with the story is not how the reader aligns her. So it seems less a dichotomy to me than, say, a Möbius strip.

Grace seems to get a high from forgery and theft. Have you had any experience similar to this?

I’ve only ever stolen a single cookie from a grocery store, but as I tried to get into Grace’s mind, it became clear that I was locked out of her daredevil psychology. Once she was stealing and forging jewelry — methodical, premeditated theft — I tried to find a way to get that feeling myself, without actually stealing anything.

Then my pet rabbit chewed up the spine of a library book. The fine to replace it was the cost of the book plus $50, and I was close to broke. So I decided that I would forge a library book. Just like Grace, I would make something equal to the stolen original, using parts of the original. I found a used copy of the book, same edition, for six dollars. I cut out the original’s endpapers, which had the library’s stamps, with a tiny knife and glued them into the replacement book. I carefully removed the ancient sticker from the spine and glued that to the new one. And then I had to find the metal strip lodged in the spine — the security strip that beeps when you walk through the gates. I tweezed it out and slipped it into the new book. I spent hours on the project and renewed the book until it was perfect. I returned it at the end of a day, when there was a big pile of returns to process, and pedaled away madly. I kept expecting to get a call, but I didn’t — though now I probably will.

We find ourselves rooting for Grace despite her many misdeeds. Why do you think that is?

When we watch heist movies, it’s so easy to root for the criminals. I think looking at them on screen makes it easier — we can root for them, even identify with them, without ever forgetting that we, the audience, are not guilty. But Unbecoming looks through Grace’s eyes, and so we can’t help but align ourselves with her, even when we feel unsettled by what we’re rooting for. That’s the question that compels me as a reader and as a writer: the desire to understand minds that are very different from my own, to untangle a psychological knot.

Unbecoming takes readers across the globe, from small-town Tennessee to New York City to Prague and Paris. Can you discuss why you chose these particular settings? Did you have to travel for your research?

Grace grew up in a tiny pond, where the few people with influence have all the influence, where there’s very little diversity of any kind, and where girls are taught to be lovable above all other qualities. From there, I wanted to send her somewhere where that cultivated lovability wouldn’t get her very far. And I knew Paris was the right choice as soon as I thought of it. Because it’s thought of as this great romantic city, it can feel especially lonely if you’re on your own. I went for several days to do research, to map out her life and soak in that loneliness, and it was easy to imagine Grace in her first days there, stretching out her school French, trying to look as if she belonged.

Do you have a favorite real-life heist story?

Several of my favorite real heists made it into the book. I can’t imagine planning a heist without reading up on the successes and failures of those who’d gone before, and so Grace and Riley had to do that research too, which gave the crime they were planning the shimmering veil of “story,” until they actually did it. My favorite of those thieves is Blane Nordahl. When he was caught again last year, the New York Timesreporter on the story sounded awfully admiring, and I can’t help but feel the same way.

One of the inspirations for Grace isn’t in the novel, because Grace wouldn’t be willing to see the similarities. Her name was Sofia Blyumshtein, and they called her Sonya the Golden Hand. She grew her fingernails very long and tucked stolen jewels under them, or she had her pet spider monkey swallow them while she distracted the jeweler.

My favorite heist, which had no place in Unbecoming, was the theft of one hundred thousand dollars’ worth of frozen bull semen, stolen from an artificial insemination business. Just one tank, only the fanciest. I prefer discriminating thieves.

What made you decide to have Grace tell her story?

I grew up steeped in Hitchcock films, where we often look through the hero’s eyes at the blond woman who needs to be saved, and who will then, in turn, save him. And as I got a little older, I began to recognize other reductive types, especially the “femme fatale,” in movies and in the old noir fiction I loved, and I wanted to find out who this woman might really be, how she became the femme fatale, the gangster moll, the damsel: what if she were one very real, very complicated person?

I had other pressing concerns — among them, the idea that the quality young girls should work hardest to cultivate is lovability. No one says it outright, but I see that message coded everywhere. Well, how far will this girl go to be loved? What happens when the love she thought she had earned is threatened? For someone who grew up without enough love, how much will ever be enough? The love Grace craves is primal, irreplaceable, and it often motivates her in ways that she doesn’t want to understand. But I wanted to push her to realization. I wanted her to “get caught,” but by herself.