“When A Man Bleeds, It’s Just Tissue.”

I first saw The Thing when I was working as a makeup artist for a student film. It was a location shoot, a farm in a small Ontario town, and we wrapped the first day right as a snowstorm started, so we drank a bunch of beers and wrapped ourselves in a lot of blankets and projected The Thing on a bare wall before falling asleep in our respective sleeping bags. In the morning I opened my kit to find that one package of my liquid blood had frozen solid, but the viscosity improved once I moved to the heated set.

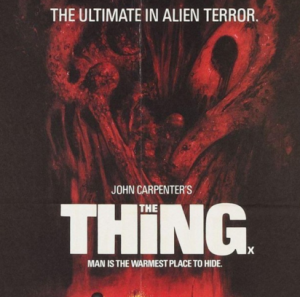

When I went to makeup school, we spent a lot of time talking about the new technological developments in our industry: airbrushing for high-definition film was becoming a new mandatory skill, for example. Movies like Lord of the Rings and Pirates of the Caribbean were blending prosthetics and puppetry with CGI and animation for increasingly realistic results. Our teachers were exceptionally skilled artists, but they had no background in the kind of work our future employers were expecting us to do. And so perhaps as a reactionary impulse — out of loyalty to our teachers or prioritizing traditions over innovation — a lot of us became much more interested in studying the work of previous makeup artists, people like Robin Bottin, who created the truly gruesome puppet monsters for John Carpenter’s remake of The Thing. He also, for reference, was the makeup artist for Total Recall and Basic Instinct, so he is a real hero of mine for a lot of reasons.

Anyway! I loved watching The Thing with a bunch of film nerds, trapped by snow and cold just like the characters of the film, and I love watching The Thing now. I love it because it is an ugly, ugly movie; I’ve seen it dozens of times and I’m still horrified at the gratuitous gore. The “Thing” in question hides inside humans and animals, and when it’s forced out it rips through bone and flesh, so, sure, the puppets and robots and prosthetics used by Bottin stretch and expand and leak fluids of all kinds of colors and consistencies. It’s like Bottin learned every possible kind of sinew in the human body for the sole purpose of making you watch him destroy it. Some horrors include: a maybe-human burnt to a pile of curled limbs, a corpse with a half-melted face, a man who froze while bleeding to death after slitting his own throat, a dog’s bloody face peeling itself off, a gaping body cavity with teeth that bites off a doctor’s arms before bursting into green stringy goo, and other kinds of metaphors for the chilling realization that inside every human lurks the genetic possibility of total annihilation and planet-wide destruction. You know, normal stuff!!

At one point, Kurt Russell’s character says: “When a man bleeds, it’s just tissue.” He’s trying to prove that once a human being is overtaken by the Thing every part of him becomes dangerous; even a severed head isn’t proof of death. But that’s kind of the charm of this sort of old-school attitude toward makeup and special effects. We know what it looks like when a man bleeds — the loss of tissue — so the realism offered by post-production CGI isn’t really the appealing part of watching science fiction or horror movies play out our worst subconscious fears. The puppets that play the Thing don’t look like anything we’d see in reality, and they don’t move like anything of this planet, and that’s why they endure decades after the release of this film. The effects are solely of a kind of imagination and skill unique to a place and time. We want, probably, something that looks worse than real.