Wait, HOW Do You Be Good?

by Alexandra Molotkow

From New York magazine:

Researchers at Wake Forest University recently won a $3.9 million grant intended to fund a three-year research initiative studying the most morally upright people they can find, nominated by the people who know them. They hope that these “moral superstars,” as the researchers dubbed them, will provide some lessons for the rest of us on how to be good.

About half of the grant will be awarded to scholars — psychologists, yes, but also philosophers and theologians, Fleeson said — who come up with exciting and innovative ways to study morality. Fleeson said it’s about time researchers started to take the study of morality as seriously as something like cognitive ability. “We spend a tremendous amount of energy identifying cognitive talent,” he said, “and yet morality is at least as important as cognitive ability.”

I am all for the study of what makes good people good, but I’ve always felt a little baffled by, and curious about ethics as a field of study. In university, I remember thinking how goofy my ethics courses seemed; the question of how to be good seemed to boil down to “it depends.” I wasn’t amoral (though I was an ignorant brat), I just thought, how does the trolley problem affect me, or anyone?

At the time, all those wacky thought experiments seemed ridiculous and unhelpful. I know I was wrong, but not why I was wrong. So I’m revisiting Judith Jarvis Thomson’s famous “Defense of Abortion” from 1971:

But now let me ask you to imagine this. You wake up in the morning and find yourself back to back in bed with an unconscious violinist. A famous unconscious violinist. He has been found to have a fatal kidney ailment, and the Society of Music Lovers has canvassed all the available medical records and found that you alone have the right blood type to help. They have therefore kidnapped you, and last night the violinist’s circulatory system was plugged into yours, so that your kidneys can be used to extract poisons from his blood as well as your own. The director of the hospital now tells you, “Look, we’re sorry the Society of Music Lovers did this to you — we would never have permitted it if we had known. But still, they did it, and the violinist is now plugged into you. To unplug you would be to kill him. But never mind, it’s only for nine months. By then he will have recovered from his ailment, and can safely be unplugged from you.” Is it morally incumbent on you to accede to this situation?

…and it is useful. I support abortion on multiple levels — personally, culturally, ideologically — and I think of access to safe abortion as a moral must. But it’s good to examine your own conclusions. I think the older you get, the farther away from college and deeper into the practical, the less likely you are to seriously entertain the opposite view. Thought experiments make it fun and easy:

If I am sick unto death, and the only thing that will save my life is the touch of Henry Fonda’s cool hand on my fevered brow, then all the same, I have no right to be given the touch of Henry Fonda’s cool hand on my fevered brow. It would be frightfully nice of him to fly in from the West Coast to provide it. It would be less nice, though no doubt well meant, if my friends flew out to the West coast and brought Henry Fonda back with them. But I have no right at all against anybody that he should do this for me.

And sometimes they are lovely little poems.

suppose it were like this: people-seeds drift about in the air like pollen, and if you open your windows, one may drift in and take root in your carpets or upholstery. You don’t want children, so you fix up your windows with fine mesh screens, the very best you can buy. As can happen, however, and on very, very rare occasions does happen, one of the screens is defective, and a seed drifts in and takes root. Does the person-plant who now develops have a right to the use of your house?

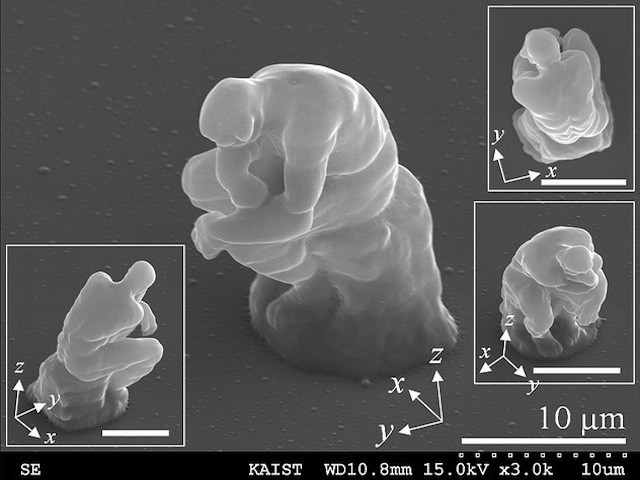

“Most amazing picture of a Thinker made by a Korean Professor called Dong-Yol YANG,” by Frank E via Flickr.