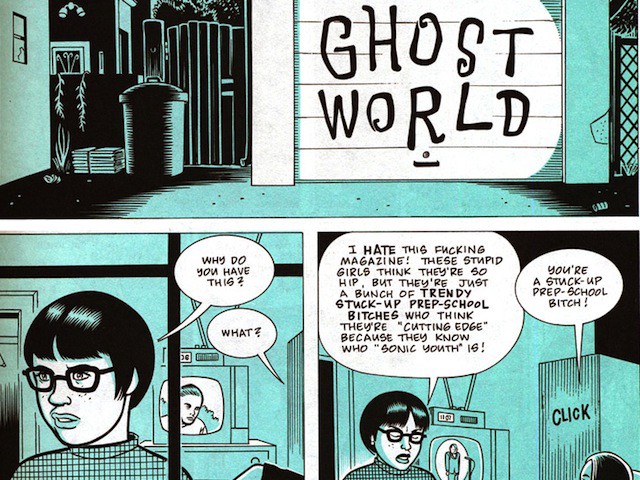

Fine, Whatever, We Still Love Ghost World

by Alexandra Molotkow

Moving to a new city is tough, mostly because you can only haul so many books with you, so you have to figure out which ones are super meaningful and significant and necessary to your life forever. For me, a few were obvious: Ask Dr. Mueller by Cookie Mueller, Cruddy by Lynda Barry, White Bicycles by Joe Boyd (which actually belongs to my friend David, sorry David, I have your copy of White Bicycles it’s safe with me here in New York), Bart Simpson’s Guide to Life, and my teenage version thereof, Ghost World by Daniel Clowes.

I wasn’t going to not take Ghost World. All the same I find it difficult to talk about Ghost World — not because it meant so much to me that it’s hard to find the words, but because having loved Ghost World says something that maybe I’d rather not say. Ghost World is a brilliant comic about a selfish brat with a persecution complex who treats other people like bendy toys and talks over her friends. I think I’d have been a better teen if I’d never read it, but that’s exactly the kind of thing Enid would say, blaming other people for her problems.

Enid also has a lot of power. If Ghost World is a feminist whatevery whatever, it’s a feminist whatevery whatever because the girls in it are characters — real, dynamic characters implanted with self-replicating personalities — not because they’re paragons of girlhood. There’s an “empowerment” message, if you want it, but it’s maybe not the healthiest one: Enid’s power consists, in large part, of shrinking others down to pocket size. She’s aspirational, in that she’s a mean teen with amazing taste and who owns exceptional tchotchkes. But she “utterly loathes” herself.

Ghost World gets better every time I read it, and I’ve read it hundreds of times. It still frightens me a little how well Daniel Clowes managed to nail the teen-girl brain. When I first read it I was preoccupied with the dynamic between Enid and Rebecca; now, the dynamic I fixate on is that between Clowes and his girls — a 30-something man and his teen pals, both characters and readers. Enid has a lot of contempt for her creator and those like him; when she goes to meet him, during an appearance at a(n empty) zine store, she decides he’s an “old perv.” Clowes has said it seemed only fair to write himself as she’d really perceive him. Because he writes her as a person, though, her contempt isn’t exaggerated or fetishized. It’s just one person’s response to another.

All the same, Clowes does show an affinity for pathetic little men. Rereading the book, the characters who elicit the most compassion are the weirdos Enid collects: the “Bearded Windbreaker” she calls from the missed connections and sets up on a fake date; Bob Skeetes, the lonely astronomer and “grisly, old con man… like Don Knotts with a homeless tan” she stalks and prank calls; the guy she loses her virginity to and never speaks to again, who sends her a 10-page note telling her how in love with her he was; “Weird Al,” the sad waiter at the ’50s diner; and the sweet dad she takes for granted.

Enid hurts their feelings. Not that we’re supposed to side with them, only to notice. It’s not really Clowes’s job to judge Enid — and if he seemed to be advocating that teenage girls be nicer to old men, well that would actually be hilarious and after I’m done writing this I’m going to imagine a cartoonist writing propaganda to encourage teen girls to be nicer to old men — but she is judgeable, because she has agency, which is why she was so available as an alter ego.

In 2001, when I’d have read the comic, there weren’t that many cultural products that “spoke to me,” although this would be the place to acknowledge that both the book and movie are overwhelmingly white, and middle-class, and I am not going to complain about a shortage of white, middle-class girl characters, not that you have to be white or middle-class to relate to Enid Coleslaw. Having been lucky enough to grow up with Ghost World really just reinforces how important it is to be able to see yourself represented, whoever you happen to be. But, I will say, when you’re not used to seeing yourself drawn as a person, it’s hard to believe you have any sort of effect in the world or on other people, particularly those with more power than you. I’m not sure I knew how to handle that.

At my old workplace, we sold an “Enid doll” behind the counter. I remember a regular — an older guy — coming in and checking us both out for about ten seconds before bursting into laughter. It stung a bit, even though I’d been cultivating that comparison for several years by the time he was kind enough to notice. I’d rather leave Enid in Toronto. But I need the book with me because it’s just really, really good.