Kiss Me With Those Red Lips

by Chelsea G. Summers

I own nine tubes of red lipstick. All are unapologetic reds. There’s nothing natural about them. Pressed against a white shirt, all leave a mark. None look like anything other than what they are: paint. These nine tubes have names like “Rioja,” “Outlaw,” “Vampira,” and “Red Velvet”; two are the same shade (“Port,” a dark blood red that a wicked stepmother would wear) because I was afraid I’d lost it and bought a new tube.

I don’t limit myself to red lipstick, though I favor it. I also have three tubes that fall in the family of exuberant, optimistic pinks; a couple that err on the cranberry side of natural; and one really lovely violet.

Some of my lipsticks are the classic twist-out, circle-in-a-rectangle tubes — the kind that film noir stars pulled from their purses and applied as a plot point. Others employ new lipstick technology where a wand sweeps a magic liquid that dries to a satin on your lips. Others resemble crayons, fat toddler-sized pencils that draw a fetching mouth atop my lips. I love my lipsticks. I have many, and I want more. Of all the makeup in my bag, lipstick is my favorite.

It has not always been thus. A stripper in the ’90s, I defined myself as a lip-gloss girl. I came to stripping late — I didn’t start until I was 30 — and part of my self-identity as a stripper was the goopy, shiny, sugary, non-threatening gloss with which I shellacked my lips. “All dancing girls are nineteen,” says the Japanese proverb, and to my thinking, lip-gloss was a nineteen-year-old girl’s game. Most women begin stripping when they’re barely legal, and most strip-club patrons think they want a girl. I’ve terrific genetics but I use makeup as I used every other artifice: to create fantasy. As Cece, my stripper name, in my Lucite shoes, Lycra dress, and shiny lip-gloss, I inhabited a fantasy concoction who was young, available and not especially intellectual. It was a fantasy that sold; even I bought it.

As I buy lipstick now, I once compulsively acquired lip-gloss. I owned many jewel-bright tubes in hues ranging from frosty pinks to berry reds. The bulk of them would’ve complemented Barbie. I loved the sweet smell, ejaculate stickiness, and hint of clean-limbed debauchery that is peculiar to lip-gloss. Mostly, though, I loved how lip-gloss extended the promise of easy approachability, a promise that its gluiness rescinded. It looked like icing and it acted like a tar pit; lip-gloss was the desirable mirage I wanted to be in the world, and I was slow to renege it. Lip-gloss is the opposite of intimidating to both its wearer and its audience. It’s not difficult to apply — you rarely need a mirror — and it looks like it’ll be gone in one swift sweep of a sleeve.

For years after I quit stripping, I stayed true to my lip-gloss love. “A sentient, carbon-based life-form with an insatiable need for lip-gloss,” read more than one of my online dating profiles. And then, about two years ago, I fell in love with lipstick. It started with Makeup Forever 52, Rebellious Red. Drawing its crimson on my lips felt like entering my own castle, but I wasn’t immediately ready to make it my home. Unlike ephemeral lip-gloss, lipstick looms large and fortress-like. It requires planning and reflections, lip brushes and lip liners, makeup remover and tissues. Lip-gloss is a one-night stand; lipstick is a commitment.

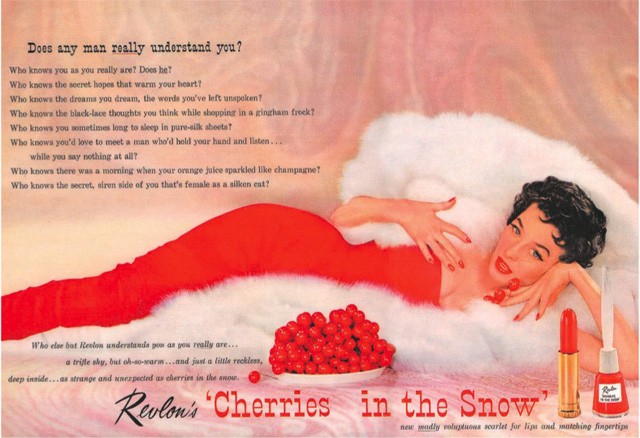

More than that, for a long stretch of my adulthood, lipstick felt somehow more assertively sexual than I wanted to appear. Lip-gloss played at a shade of sexuality that lipstick required. If lip-gloss was colored by a young girls’ romantic imaginings, lipstick was etched with a woman’s experience. Pat Benatar put another notch on her lipstick case. Anaïs Nin’s seductresses rouged their “sex” with lipstick. I couldn’t imagine either Pat or Anaïs letting their lips get within ten feet of a gloss. Pat and Anaïs would laugh at a lip-gloss; their derision would ring in lip-gloss’s ears.

Lipstick, I think, isn’t merely a woman’s game; it’s the game of women of a certain age. It’s like mah-jong or bridge. It takes a mature woman’s wiliness and patience. Like card games and gin tonics, you probably were first exposed to lipstick by your older female relatives, who made it look mysterious and sophisticated. I was. Like most women that came of age in the first half of the twentieth century, both my mother and my grandmother wore lipstick. A hippie, my mom reserved her lipstick use for New Year’s Eve and anniversaries, but my grandma wouldn’t be parted from her daily use of lipstick, even when she was in the hospital. The last thing she did before leaving her house was open her compact scented with Prince Matchabelli, remove her lipstick and her lipstick brush, and carefully paint a scarlet circle over her mouth.

Well before I was born, my grandma had lost most of her lips to cancer. Treated with X-Rays for her adolescent acne in the 1920s, she’d developed aggressive melanoma in her late thirties. The skin that had plagued her so as a teenager threatened her life as an adult, and she had suffered a tricky operation in the 1950s. Doctors removed her cancerous skin on her nose and mouth, and then pulled a sheet of skin from her chest up and over her face as a graft. She stayed in hospital, essentially wearing a turtleneck of her own skin until the graft attached, when doctors could separate her from her turtleneck.

The experience left her with a lifelong fear of the sun and a self-consciousness about her mouth. As a young girl, her lips had been full and lovely; as an adult, they were thin slivers. Lipstick was the way my grandmother made her mouth legible. Lipstick was more than my grandma’s way of feeling better about her loss. It was a way to mark her sexuality. “It hurts to be beautiful,” my grandma used to say, but what I heard was how much it hurts when you’re not.

These days, the thought of wearing a gloss feels willfully naïve; it feels as disingenuous as it would for me to wear any of the stripper costumes I kept out of nostalgia. They’re of the past, and I’m cool keeping them there. Wearing lip-gloss feels like it would be a lie. I no longer have a desire to make myself a desirable, approachable, shiny object. I don’t want to look as if I’m easy to kiss, simple to please, or easy to love. I want to appear as if it takes work to get in my life — but that this work is very, very rewarding. I have no problem with men finding my scarlet mouth daunting; let them be daunted. Those I find worthy can kiss my red lips, and if it gets on them, they can consider themselves lucky.

Like my grandma before me, I rarely leave my home these days without my lipstick. Beauty commonplace tells women of a certain age that red lipstick “ages” them, but I have no fucks to give for commonplace. It took me decades to claim the lipstick that is my birthright — and to realize that my makeup choices do more than merely please men: they honor the woman I have grown to be — a woman whose first fantasy is one that pleases herself, a woman who can keep a commitment and get out a stain, a woman who knows the value of her past, and a woman who isn’t afraid to put her mouth on a little crooked.

Chelsea G. Summers lives in Manhattan and writes about almost exclusively about sex.