Your Place, Your People: An Interview With Elisha Lim

by ManishaAggarwalSchifellite

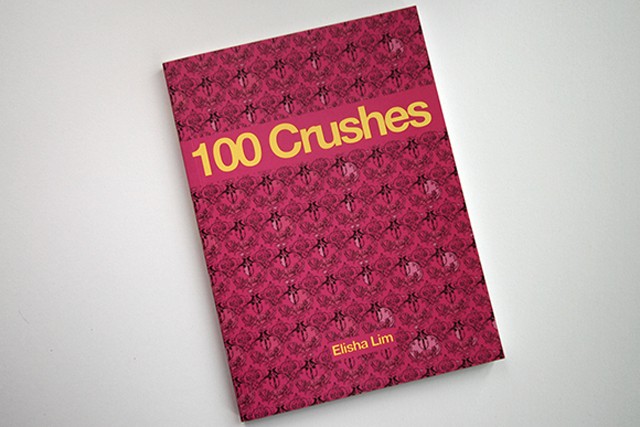

Elisha Lim has a lot to say. The graphic artist, illustrator, and filmmaker has spent years telling stories of queer and trans people of color through pin-up calendars, comics, short Claymation films, and writing. In their new anthology, 100 Crushes, Lim explores the complexities of queer life, from monogamy to buying a suit to changing their preferred pronoun to “they.” 100 Crushes has been nominated for a Lambda Literary Award, which celebrates the year in LGBT literature.

Lim is an artist and an activist, and much of their work is in pursuit of increased visibility for queer people of color who are relegated to the margins of mainstream and activist circles. Their artistic work deals with racism, mixed-race identity, gender performance, and queerness. Lim has held film screenings in North America and Europe, curated art shows in Toronto and Montreal, and shown work across the U.S. and Canada. In 2013, they were named Best Emerging Director by Toronto’s Inside Out Film Festival for their short film They.

In 100 Crushes, Lim speaks to their specific experiences, as well as the universal sigh of relief that comes when you find your place and your people. In The Illustrated Gentleman we see them go shopping with their queer friends; Sissy pays homage to the “sissies and the femmes that inspire us,” a set of profiles in which Lim brings the voices of queer and trans people of color into conversation with one another and the reader.

At the same time, many of their comics are about the joys and struggles of everyday life: seeing a sexy construction worker on the street in Spain, reflecting on the influence of 1980s television in their sexual awakening, and realizing they might be a jealous person after all.

I spoke to Lim about their book, their favorite feelings, and how to navigate a constantly evolving queer community.

Congratulations on your book, and on your recent Lambda Literary Award nomination!

Thank you! It’s very exciting. Doing the book has been a long journey — it’s a compilation of five years of work.

What was the idea behind 100 Crushes? How did you start putting it together?

I really wanted to tell different stories from my life and the lives of people I know. I knew I wanted to make queer people of color a focal point and make them really visible. The first comic in the book [100 Butches] is older, so there are more white people in it, but in the rest of them, I made the decision to have people of color front and center.

You went on a book tour last fall. What was it like touring for your own book at this time in your life?

I’m finding that it’s hard to keep up with queer culture! In 2010, I toured with Michelle Tea, and she was like a rock star, people were so excited. That tour, and a couple of the ones I’ve done since, were more like “rah rah queer community!” which was great. This tour [for 100 Crushes] is the first one I’ve done with non-gay audiences, which has been interesting. The publisher [Koyama Press] is a comic arts publisher, not a queer publisher, so it’s a new readership.

[On the 2010 tour] I knew exactly what I wanted to say and do, and I really wanted to make sure that I was talking about queer people of color. Now, with Tumblr and other internet communities, there’s so much leadership on those issues coming from so many different places. In a way, I can no longer tell what people are excited about, which makes me feel like I’m behind all the time. In 2010 I was like, “I’m a leader, I’m talking about anti-racism,” and things that were on people’s radars. While that was happening, I went out to comic festivals and conferences, and I was just a voice in the wilderness. I was like, “I don’t know what these straight people want! These are just my stories, take it or leave it.”

I feel that way when I go to queer venues now. I’m not sure how to do readings like I used to because things change so quickly. Like with the Lambda Literary Award nominations, the other people on the graphic novel list are such a hodgepodge. There’s a kind of throwback novel called Pregnant Butch: Nine Long Months Spent in Drag by A.K. Summers, which sounds kind of older. There’s another one called Snackies, by Nick Sumida, who writes short, Twitter-style anecdotes. It’s just all over the map and I have no idea what the trend is. It makes me sounds like a grandpa. Maybe I am one.

I could see how it would be hard to figure out what might bring people together if there’s such a diversity of interests online.

Now when I’m reading to a room, every one of those people could be their own blog king. Each person could be a local expert on a particular topic. I think that is wonderful. It’s harder to be the one on stage, wondering “am I still trendy?” I’d rather have it this way, though. One hundred celebrities rather than one.

That might be more universal, though! I felt like I really connected to your book, even if we don’t have the same experiences of race and gender and sexuality.

Totally. I love the way things are changing.

One of the changes I wanted to ask you about was this controversy with the Canadian gay and lesbian newspaper Xtra! from a few years ago. The newspaper didn’t want to use your preferred pronoun “they” when identifying you in a profile, and you started a petition to get them to adopt your pronouns.

That seems so outdated now!

I know! It wasn’t that long ago but it feels like a lot has changed.

I know. How embarrassing for them. I knew it would be, too, when it all started. Things have changed drastically since then, for me, and in general.

On that topic, I’d love to give a shoutout to my workplace, the Power Plant Gallery. After I asked they called a staff meeting and said, “We want you to respect that Elisha’s pronoun is ‘they.’” When they wrote my employee feedback form, they also wrote everything with my pronouns. It was so amazing to see it in a formal, bureaucratic, administrative setting. I know not every workplace is like that, and I’m lucky that mine is, but [that attitude] is so much more commonplace. When I tell someone that my pronoun is “they,” they say “oh, I’ve heard of that.” That’s a huge change.

But if I’m really frank about it, things have changed so much and so well on that front that I’m almost bored of the whole issue. I want to talk about other things: how people of color use “they,” how language changes when you learn a new language, things like that. It’s great that I’ve gotten to a point where I feel like I can take that issue to a new place.

One of my favourite things in the book was the section on jealousy. On one page, you’re fantasizing about your partner’s ex and thinking, “She was probably working on an indispensable contribution to the literary canon.” That hatred and fascination is such a funny and also terrible feeling to have. Why did you choose to write and draw on those topics?

I love jealousy; I think it’s so fascinating. Through visual cues, I wanted to tell a story about my relationship with my sister and my mother. That’s what that chapter is actually about, but it’s pretty subtle. The chapter ends with a picture of me talking to my sister, and then with a picture of me lying in bed near a photo of my mother. I put clues throughout the different stories. Like, there’s one where I’m telling a story of jealousy, but it’s through a Facebook message with my sister. She’s telling me “you didn’t craft this story really well,” and I’m writing to her to impress her.

When I talk about idolizing someone’s ex-girlfriend, that person is based off an archetype of my sister, who is an amazing writer. In the room where I visit her in the picture, she’s writing a novel, so she’s got her writing tools and her storyboards. Then I talk about a woman who’s the life of the party, drinks red wine and wears a white dress, and then in the photo, my mother’s the one in the white dress. So it’s really about how I idolize those women, and try to gain their approval, the two powerful women in my life.

For the most part, though, I’ll choose a topic I know is on people’s minds. When I was writing the chapter “Sissy,” I was getting into questions like: how do we deal with femininity, as feminists and trans people? I knew that was a hot topic. Talking about “they” in the book was kind of a sell-out move, because obviously people were talking about it. That last chapter on jealousy was a real luxury, and it’s what I want to explore more in an MFA. Like, if I have the freedom to not worry about whether something will sell or not, or if people are going to pay attention, then I can just play.

That drawing of you talking to your sister felt so vulnerable. It really got to me, because I get so nervous about bringing work to someone who is so good at what I’m trying to do. Who do you look to for guidance or inspiration?

I wanted to put that story at the end of the book because there really is just one person I always go back to, and it is my sister. It’s sort of like the coda or bookend, a dedication to her. The whole process of these comics has been to go into her room and ask her for help. At the very end, without any words, just visually, I wanted to say, “I know I’m always coming in here and looking for you.”

Do you see your work going in a particular direction, or are you planning to continue with drawing?

I started a film project about prayer called Queers Who Pray, where I had queer people of color reciting prayers and I would draw their portraits. I did an Indiegogo campaign for it, but I’ve hit a bit of a drawing block and haven’t been able to finish it yet.

I’m hoping to, at some point, write a book more about jealousy. Something more imaginary, on the topic of forgiveness. I find forgiveness to be the most taboo thing. I don’t want to forgive; to me it’s totally unpalatable and disgusting. But I know that’s irrational and not sustainable. I’d love to do more of that kind of storytelling in the future without as much emphasis on the identity politics. Just telling stories and talking about feelings, whatever subject that captivates me.

I don’t want to live my life in anger. So I wanted to look at that phenomenon, which is almost like a suicidal tendency, to love and cling to anger. It’s not smart, but it’s such a strong drive. For me as an activist, call-out culture for example, or attacking humans online, I love those things, but they’re so anti-life. They’re so pro-death. So I’m investigating the idea of forgiveness next.

Fun is so important! My next steps will be all about breaking away from conventional patterns of art and writing. I want to be more imaginative and just launch off into something new and exciting.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Manisha Aggarwal-Schifellite writes and edits in Toronto.