My Mother’s Child

by Huda Hassan

I will always remember one specific evening after school in 1999. I was sitting in the living room of our apartment complex, wasting my day in front of the TV, when my mom barged in crying. It wasn’t the first time I had seen her emotionally fall apart in front of me nor the first time her nine-year-old daughter would comfort her while she broke down.

I was already beginning to accustom myself to the peculiarity of living with an uncle suffering from schizophrenia at this point: frequent stares from our neighbors in fear of his presence; fighting with kids in the neighborhood who taunted him while he publicly spoke to the voices in his head, watching him struggle to distinguish between what was real and not real, or moments where I would wipe my mothers’ tears after she watched her brother have another episode.

The love I used to receive from my abtiyo — “maternal uncle” in Somali — during my childhood is indescribable. Whenever he would visit me as a toddler I would be glued to his lap as he would tickle me and ask how my day was. Not having children of his own he treated me like I was a gift to him; I was spoiled by his love.

Now as an adult I rarely see him. When I do, I’m accompanying my mother on one of her routine trips to the group home he resides in. Over the years I have become afraid of addressing his current conditions; I fear the resentment, devastation, and disappointment that has grown within me as my uncle’s health has worsened. My mother, who is generally stronger than myself, has become content with his circumstances, whereas I remain in denial. I’m more inclined to avoid him entirely.

This is the third group home my abtiyo has been situated within in the last decade. Our encounters are radically different than they were when I was a kid: his face still lights up when he sees me until his attention goes elsewhere mid-conversation and I begin to feel that I am talking to a complete stranger. He struggles to grapple between what’s real and what is not.

I visited my uncle in July, a few days before I left for my first trip back home to Somalia. I had brought him spending money for the week and some cigarettes. He was grateful and visibly happy to see me, at first.

“You’re so tall, abtiyo. How is school going?” He was enthusiastic to get an update about his growing niece.

“Abtiyo, I finished school last year, remember? I’m thinking of applying for graduate school now.” I never enjoyed emphasizing my accomplishments to him, especially mentioning graduating from University of Toronto — the same school he was enrolled in before he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. I decided to change topics.

“Abtiyo, I’m actually going to Somaliland next week. It will be my first time.” The news escaped my mouth immediately. I imagined he would be pleased to know that his 24-year-old niece, the one who was born in Toronto and has never spoken her mothers’ tongue, was finally going to see their homeland.

The bright smile on his face receded after he heard me. He tactfully began to wrap up the bag I had brought him that contained enough cigarette packs for the next few weeks before abruptly ending our short conversation:

“Enjoy Burco and say hi to Ayeyo [grandmother] for me,” he said before walking back into the building.

I was to meet my grandmother — his mother, who he hasn’t seen since the 1990s — for the first time, and spend the rest of my summer in the place he misses the most; the place he would rather be instead of wasting away his years in the country he came to for a better life but instead found psych wards, group homes, and a life-long depression.

I was overwhelmed with guilt that day, a feeling familiar to me after most of my interactions with my abtiyo now. I’ve been given a chance that was taken away from him when he was my age. I might be a continuous reminder of what life could have been for him if he were healthier; a reminder that life gives to some while taking away from others. As always, our short encounter ended in an outpour of tears as I walked back to my car.

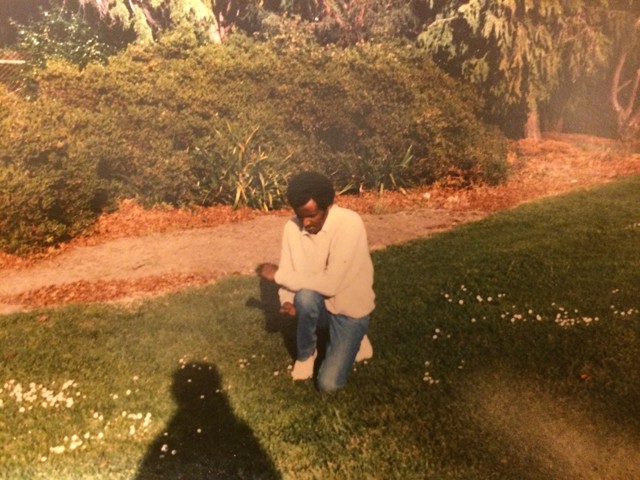

My mother immigrated to Toronto in 1987. She left her hometown, a city in north Somalia called Burco, and moved to Brooklyn for a few years before making her way up north. It was an exciting time for her in Toronto: she was a pretty and petite twenty-something in a new city that presented ample opportunities for her. Eventually she enrolled in college and was finally alongside her baby brother who had navigated his way up to Toronto from California. He was previously studying in the United States, but had to drop out of his classes during his fourth year once the civil war in Somalia had broken out. Their family was no longer capable of paying for his education. Only in his early twenties at the time, he was energetic, charismatic, and known to be exceedingly bright for his age. He was eventually accepted into University of Toronto as an Economics major with hopes of achieving his PhD before he turned thirty.

When my mother and my abtiyo first moved in together in 1987, it was a convenient arrangement: they both pursued their studies and steered their way through the immigrant experience, hoping to eventually achieve citizenship. The last time they lived together was before my mother left Burco in the late 1970’s. For the following ten years they would both have different homes in various parts of the world for economic and educational pursuits. My mother went from Mogadishu to Kuwait to New York while my uncle journeyed from Cairo to America. Living in Toronto gave them ample time to catch up on the many years they missed with each other.

However during that time my mother noticed something different about her younger brother: he was distant, sensitive, slowly isolating himself from the world and always reserved when in the company of others. When he wasn’t at school or working he was locked away in his bedroom, separating himself from the rest of the world.

This eventually caused friction in my mother and uncle’s relationship; she wasn’t aware he was displaying signs of a potentially larger issue and that these newly developed characteristics spoke to something deeper. She would try and persuade him to join her when she would go out with friends or encourage him to leave the house during his spare time and pick up some hobbies. At first she thought it was temporary behavior, perhaps because he was overwhelmed with school. One year later my uncle dropped out of school and was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Growing up I was accustomed to watching my mother suffer in silence as she tried to navigate my abtiyo’s condition. Back home in Burco, the general concept of suffering from mental illness is regarded as taboo, often associated with being “crazy” or “possessed.” My abtiyo’s suffering challenged her in many ways, particularly with confronting her own internalized ideas about mental health and the stigma of an entire community.

At first her immediate reaction was largely spiritual — she tried to heal his condition with spiritual leaders. My mother dedicated an enormous amount of time, money, and energy trying to save her baby brother but my uncle’s situation grew worse and worse, eventually leading to his repeated hospitalization.

By 1988, my parents had met and were married within a year. Together they watched as my uncle’s friends and peers disappeared and his suffering increased. Having had to drop out of school for his well being, my mother watched as all of his childhood dreams dissolved. All of his academic ambitions and reasons to leave home during his adolescence were shattered, while my mother was achieving everything he had hoped for himself: marriage, family, an education.

My abtiyo’s experience has directly impacted my mother’s career choice. In the late 1990’s, now the mother of three children, she enrolled at York University to study Sociology. She also began working with the Somali community in efforts to address mental health issues that were prominent and effecting the Somali diaspora heavily. Her goal, with others, was to confront the stigma against Somali’s suffering from mental illness — people like her little brother. Eventually she began working with a family mental health organization where she exclusively helps racialized families with relatives suffering from mental health issues — people like herself.

Despite my mother transforming her pain into a positive by dedicating the past decade to helping those facing narratives similar to hers, my uncle continues to suffer. Every time I begin to think of him I imagine him in the same position he’s in every time I visit: starring blankly into the television placed in the living room of his group home, in silence and alone, with his receding hairline and now greyed hair from three decades of pain.

Many years ago a patient in one of my uncle’s group homes killed himself. In the midst of playing cards with my abtiyo, he excused himself from the table, walked outside their home towards a nearby train track, and killed himself in the middle of the day. I didn’t know this man but I often reflect on what his life was like: did that man suffer for twenty-five years and finally decide to bring it all to an end? Was he tired of knowing that he left his home country during the peak of his life for opportunity only to waste away the rest of his years in a group home? Was he tired of the voices, hallucinations, and the constant struggle of identifying if what he was seeing, hearing, or feeling was real? Would the end of his life be the fate of my uncle?

A part of me has always lived with the paranoia that a life suffering from schizophrenia was destined for me. Knowing that my chances of suffering from mental illness are higher than many around me, I’ve always been selective of how I treat my mind and my body, but the paranoia continues to exist. There were no warning signs during my abtiyo’s adolescence that he would suffer a life-long battle against schizophrenia. There aren’t always signs. Sometimes my paranoia transcends to panic that it could be Guled, my twenty year-old baby brother, who would be the next potential victim of mental illness in my family and that my real fate has been that of my mothers’ — helplessly watching her baby brother suffer as she does the same in silence.

The repercussions of mental illness are not exclusive nor an individual experience. It becomes a communal occurrence; the rippling effects slowly wash over the victim before moving to his or her loved ones — if one is even lucky enough to have loved ones stick around. Knowing someone who is suffering from mental illness is isolating, confusing, and hard, but most importantly, it is lonely. It is a guilt-ridden experience that places family members and friends in positions where they suffer silently as they grow ashamed, feeling like their own pain is not enough. As a parent, sibling, or friend tries their best to help someone they love, it becomes easy for their own suffering to become neglected and shoved aside.

I recently asked my mother when was the last time she cried. It took her a while and I thought to myself how little time she ever spends thinking about herself between worrying about her brother and taking care of her three children and her home.

One night, a few months ago, she was sick and fatigued from a long day at work. Abtiyo had called her repeatedly in dire need of cigarettes, so she made her way to him. Her little brother, now a fifty-year-old man, was waiting for her eagerly by the front door when she arrived.

Grateful for her making the forty-minute drive to him, he smiled as he began singing to her in Somali: “ina hooyahayow, indho haygu nuur kay ku il doogsadeenow.” My mother’s child, you are the light in my eyes; when I see you everything becomes green and beautiful.

Huda Hassan is a passionate, fragmentary girl, maybe? She is a writer based in Toronto interested in culture, identity and things that make people cry. You can find her on her blog Birds Nest.