Happy Birthday, Selena Quintanilla-Pérez

by ChantalBraganza

When I was a child, my family had a Friday night tradition: my mother would make a big pasta, my dad would crack open a can of Faxe, and my brother and I would argue with them about what music we were going to listen to that evening. It sounds so earnest, so boring, but we really did fight. I’d hide my mom’s Boney M tapes in the laundry while she got into marital spats over my dad’s weird obsession with hammy Mexican singer-songwriters. My brother once snapped my Jewel CD in two.

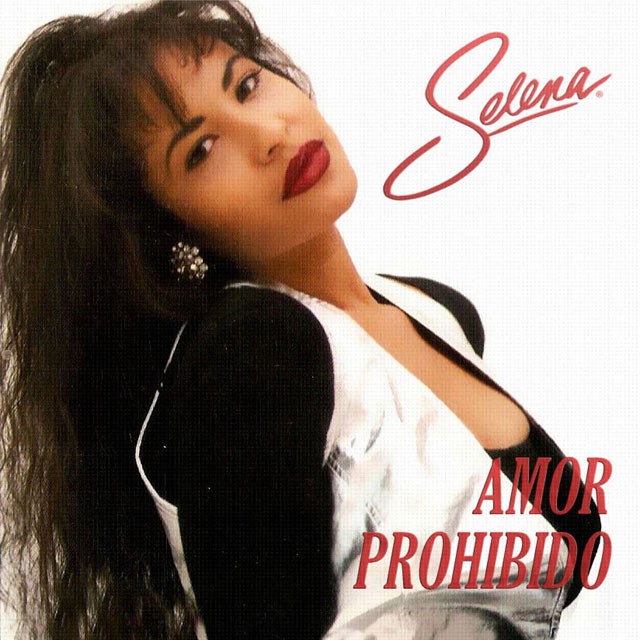

There were only two albums met with minimal complaints. Both were by Selena Quintanilla-Pérez: Entre a Mi Mundo and Amor Prohibido, two early-nineties releases that propelled the Texas-born Tejano singer into international Latin pop stardom and almost into the English-language market before her death in 1995. Selena made everyone happy. My mom got her cumbia-inflected dance tracks, my dad his mariachi fix, I had my emo love ballads on repeat — and my brother didn’t have to listen to any more Boney M or Jewel.

Aside from being an inexpensive form of family counselling, listening to Selena as a kid filled gaps I’d learned not to see. Singing along in Spanish helped me keep my first language alive, the language I’ve since lost. For years, she was a just-at-home luxury; in part because she wasn’t reflected anywhere in the predominantly white Toronto suburban elementary school I attended, and because even to close family, she was more understood through her brief English-language crossover.

Selena, the 1997 biopic starring Jennifer Lopez , came out the same year our family first got Internet access. I’d seek out photo stills of la reina (the queen, as she’s often called) and show them to my older cousins. “I think Jennifer Lopez is prettier,” they’d say.

I’m not so sure Selena Quintanilla-Pérez was a “Mexican Madonna”, as English-language news outlets referred to her in obituaries after her fan club president Yolanda Saldivar shot her in the back in March 1995. The handy nickname misses that as a Spanish0language artist with bourgeoning crossover appeal, she might have stepped into a pop culture status quite different from the one Madonna occupies. In some ways, she already has.

In March 1996, 8,000 girls and women lined up in San Antonio for a chance to play la reina in the movie that would document her life. In Los Angeles, another 10,000; in Miami and Chicago, 3,000 each. In total about 24,000 people auditioned for the roles of Selena as an adult and girl — at the time, one of the largest open casting calls in Hollywood history.

In a segment for This American Life, Claudia Perez, then 18, attends a casting events at a Chicago high school. She talks to eight-year-old girls who cry through “Como la Flor” and teens who saved $135 of babysitting money to fly into the city. She also auditions herself, and wonders if the whole thing wasn’t a publicity stunt. Even if it might’ve been — Jennifer Lopez and Rebecca Lee Meza, the two picked for the role, didn’t come from casting calls — Perez’s experience of the event sounds like a fan expo of cumbia moves and bedazzled bustiers I would have killed to see. Young women becoming, loving, and grieving an idol.

Unlike past celebrities who needed to slip out of Latina skins to break into American fame (Rita Hayworth dyeing and re-shaping her hairline to look like this, Raquel Welch spending 40 years as a Hollywood star before claiming her Bolivian heritage), Selena was adored for features that placed her squarely in the image of the brown-skinned Latina, still rare in pop culture today. Her hair remained black, her complexion gorgeously morena, and oh my god, that culo. Years before J.Lo took out a multi-million insurance policy on hers, and decades before Vogue or Salon gave their approval, Selena’s butt was an openly adored miracle among fans.

And with good reason.

I mean, holy hell.

For a lot of fans, obsessing over her this way is a direct inversion of the objectification it might initially seem like. “Many Latinas laid claim to Selena’s body as a means of expressing political or cultural criticism,” writes Deborah Paredez in Selenidad. “[W]hen they say Selena had a fake butt. That makes me real mad,” Perez told Paredez in an interview for the 2009 book. Commenting on her olive complexion, copying her signature dance moves and knowing precisely the shade of lipstick she favoured (Chanel Brick, discontinued shortly after Selena premiered); and its perfect replacement brand today (Elizabeth Arden Ceramide Ultra) were ways of loving a look you could identify with and see in yourself. Or perform yourself: seriously, Google some Selena drag performance and just bask.

Selena was ni de aqui, ni de alla — a U.S.-born artist who had to struggle to learn Spanish and ditch dreams of Donna Summer tunes to break into the Latino market — but she belonged wherever she placed herself. She worked the spaces to fit who she was. For a swath of second- and third-generation young adults who live with the quiet, relentless discomforts of language or identity guilt, to see this is a kind of magic. She was a daughter of strict Jehovah’s Witness parents who made her own bustiers out of bedazzled Victoria’s Secret bras. She borrowed Janet Jackson and Paula Abdul dance moves for music dismissed as an obscure “ethnic” genre. She threw disco-era references into live performances.

In the 2010 Texas Monthly oral history of her life, Brian Moore, a recording engineer who worked with Selena y Los Dinos (the band’s name before she went monomynous), describes a near Pygmalion-type childhood: Selena working to learn Spanish so she could sell songs to borderland audiences. “Those early days in the studio were hard on her,” he said. “Abraham and Manny would both be in there, correcting her pronunciation until she sang it right. That would be hard on any twelve-year-old girl, to have two guys in there correcting and correcting and correcting.” And yet her twangy English was part of how audiences understood her.

If you’ve watched the movie, remember that scene where she swaps in the English word for “excited” during a Telemundo press conference, and it’s this huge deal? That actually happened a bunch of times:

Her Spanish was not the greatest. A reporter asked her, “¿Cómo te sientes cuando te echan piropos?” which means, “How do you feel when they throw piropos at you?” A piropo is a flirtatious compliment, like, “Hey, babe, you’re beautiful,” but she misunderstood. She thought she was being asked how she felt when fans threw bottles and cans onstage, which is customary to do when you like an artist in Mexico. So she said, “Yeah, they throw piropos and cans and flowers…” And the place just fell apart. Somebody else would have been crucified, but it was the start of a national love affair.

When she was seventeen, Selena signed a $75,000 contract with Coca-Cola to star in English and Spanish Coke campaigns across the United States. Along with soda, she sold: magazines (the People magazine editions dedicated to her after the murder sold more than a million copies and launched the brand’s foray into People en Español), clothes, and, of course, records. As the first artist to sign with EMI’s Latin division, now Capitol Latin, the success of her early record deals preceded the launch of over 60 artists for the next 20 years. “EMI Latin was, is, and always will be her label,” CEO José Béhar once said.

The span of her career marked a time in the U.S. when corporate interests were starting to wake up to the monetization possibilities in catering to latinido identities and consumer desires — right around the same decade that government interests were drafting up policies decidedly not in the interest of Latino populations. In the year after her death, Selena’s Texas hometown of Corpus Christi saw an increase in border patrol policing as a result of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act.

In “Dreaming of NAFTA,” a brilliant friend and writer Kelli Korducki (ed. note: who will also be sharing some Selena thoughts later today) wrote about the mid-90s convergence of her crossover appeal and the North American Free Trade Agreement’s early touting of permeable and prosperous borders — both of which had promises never quite realized.

“One of the most criticized facets of NAFTA’s fallout has been the absurdly uneven distribution of the wealth it promised to generate for the Mexican economy,” Korducki wrote. “Few got a slice of the pie; many more, shit sandwich. If only the hopeful, class-transcending chorus of “Amor Prohibido,’” a song about forsaking money for love, “rang true in life.”

Nearly 20 years later, listening to Selena has become another form of therapy. In Selenidad, Paredez talks about the concept of audiotopias — a term coined by music critic Josh Kun to describe the private and shared worlds that music’s aural and social components can put us in. “These audiotopic spaces are what enables music to give us the feelings we need to get where we want to go.” The music is reflective; an unbeatable form of self-care.

Not a week goes by that I don’t run through a wheel of YouTube clips of live performances or give Amor Prohibido a run through. And when I do, that long-forgotten Spanish gets a little sharper. I’ll file and paint my nails and remember to call my mom. I see glimmers of her reflected in the space she had only just started to crack.

Chantal Braganza is a writer, editor, and sometimes journalism instructor living in Toronto. Her two personal saints are performers in purple: Selena and Prince.