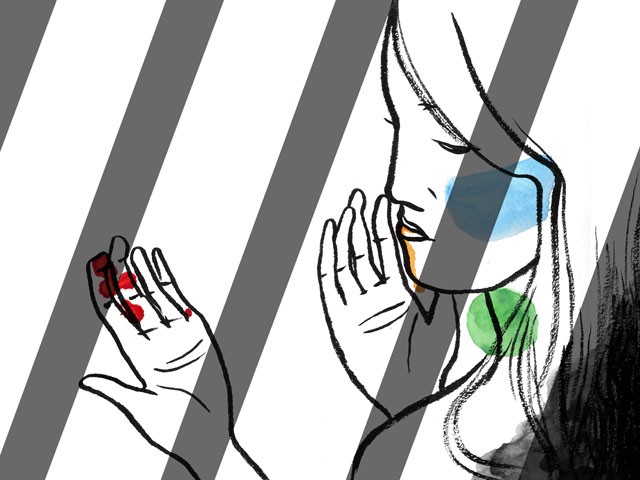

Showing My Hand

by Larissa Pham

The facts are these: many months ago, I spent the night at a man’s apartment. The circumstances were semi-platonic, tinged with an aura of romance; that is, this person had offered me the moon and I had refused, and he said, well, let me give you everything, and will you take what you can? I said, flattered by this grand gesture, I will take what I am okay with.

I was very lonely.

We talked about art.

He made me feel important.

I was used to men who made grand declarations of their affection for me. Because I saw these men as harmless, I placed myself in situations with them that might be construed as romantic. I was deliberate about my boundaries, but sometimes allowed myself to be cuddled, like a toy or stuffed animal. This was seen as strange but not unexpected, a particular and endearing flaw. My friends acknowledged that I was a very tender person, someone who craved physical contact and liked being touched.

It wasn’t so much that I was ever lonely, just that I was always around and I was always so warm. When I went home with boys and girls it was the normal kind of thing I did, and no one ever asked what happened after the door was shut. That never mattered. I didn’t think myself fast or loose, but maybe it seemed that way. It was right enough sometimes that I never bothered explaining why I wanted someone next to me, just to hold. I’m not sure I would have the language for it anyway.

In this man’s apartment, I put on a t-shirt and did not put on a pair of gym shorts. Because he said he cared about me, I felt safe. I crawled into bed and his dog whined at me. “Shh, Lemon,” he said. He got into bed next to me and we talked. I liked being next to another person. I liked the warmth.

Now my memory becomes clouded regarding the sequence of events, not because of drugs or alcohol but because it is not something I revisit. I feel guilty for how I got there, how I was already in that place, in that bed, in my underwear.

I know that I allowed this man to kiss my neck. I know that I liked it, the way I like being touched. I know I did not kiss him back. He pulled my panties down with his right hand. It was his right hand because I was on the left. I did not say anything, but I did freeze up. “Shh, it’s okay,” he said, and stroked my hair, as though trying to make me melt.

I did not say anything.

Then he put himself inside me. I felt it suddenly and I let him do it for perhaps fifteen seconds and then I said, “No, stop” and he pulled out. He went down on me and I started crying even though it felt good. Then he put himself inside me again and I said, “I can’t,” and he said, “Shh, it’s okay,” but it wasn’t. I was crying and breathing fast. I said, “No, no, no.” He attempted to comfort me. Eventually I fell asleep.

In the morning, he drove me home.

I felt sick. I felt dead. I went to class.

I was sexually assaulted my freshman year of college. It was a very clear-cut situation. The ex-girlfriend of a boy I had (unbeknownst to me) just stopped hooking up with was very drunk at a party and when she learned I was bisexual, she said, “That’s so hot!” and then pushed me up against a wall and kissed me and put her hand down my pants. I was eighteen. I was wearing a man’s white v-neck shirt and blue denim cutoffs, and black thigh high socks. She kept going after I squirmed. “Stop,” I said, and I pushed her off.

Years later, a friend of hers would recognize me at another party. “She’s not normally like that,” they apologized. It surprised me that her friend remembered, because it was an event that some part of me had diligently worked to forget. “I don’t care,” I said.

I never reported it.

If she had been a man, I don’t think I would have reported it, either.

I have not reported this latest thing, this rape that I am only just beginning to talk about.

What would I say?

When I told a friend about this man, many months later, he said, “Larissa, you were raped.” Because I looked at him blankly at first, he said it twice.

“I don’t want to think about it,” I said, and covered my face.

I felt sick. I felt complicit. I had not intended to tell a rape story, but then I began telling it, and in telling it, realized it had been rape.

The thing about the man who raped me is — I was burning to be touched, but I did not want to be touched by him. I also did not not care about him.

I knew him well. We had text message conversations that spanned hundreds of lines. We sometimes talked on the phone for several hours. I was very fond of him. His love for me, or whatever one might call it, seemed like a kind of a punctuation mark, the uncomfortable tail of an otherwise competent and friendly beast. It made me feel uneasy and good. I wanted to be loved.

Still. I didn’t owe him anything. I don’t deserve what happened. I must continue to tell myself this.

I’ve never considered myself particularly lovable, so when love is offered I’m hesitant to spurn it. I’m used to getting the crumbs of a full thing, the rest out of reach. It makes assault like this difficult, when I consider the role I’ve played in an interaction that hurt me. How I want to blame myself for it. How I can’t help but think I may have invited it in, how I don’t deserve it, how no one deserves this.

If you had asked me at the time, or ever, if I wanted to have sex with him, I would have said no. Nothing about his body appealed to me. There was nothing about him that made me want to fuck him.

Here is a caveat that only makes sense to me. I write it down as proof of how warped my boundaries were formed. If I had hated him I would be a better victim. If I hadn’t known him so well I would be a better victim. I brought this upon myself, I think. I deserve this.

The possibilities of what I could have done or what else could have happened unfurl before me like a reflection in one of those dressing room mirrors; two opposite each other and a long hallway of you stretching into the infinite distance. I’m standing there in the house of my memory, scrutinizing my face.

Was it my fault?

Did I put myself in that position, and am I responsible?

Is it rape if I know the person who did it?

Is it rape if I didn’t say no, but I didn’t say yes, and I cried after?

I want to tell you I cried, so that you know that I didn’t want it. I want to tell you I suffered, so that the story I told you is plausible. The narrative of rape is only enabled by a woman’s pain.

I must have suffered. I must be experiencing some kind of trauma. I must be damaged somehow. I am a rape survivor. I am not, however, a particularly convenient victim. I spent the rest of the night there. I let him drive me home.

Mostly, I just feel complicit in breaking the parts of me that are broken.

But this model of myself started a long time ago. This myth, this story, this coping, whatever. It starts long before I ever met the man with his dog and spent the night in his bed.

I got pretty late in life and all at once. Suddenly everyone wanted me just because of how I looked! What a thought. People were nice to me and interested in what I had to say. I was giddy with power.

So I fucked a lot, because it was easy. I never knew what was good. I considered it my lot in life, being promiscuous and pretty and sort of out of control. I thought this was something I deserved, the being hurt all the time.

In my head, understand, these are connected. I earned this. Happiness is not something you earn or deserve. Neither is pain. I deserve this. I didn’t. You don’t. I am complicit.

[IT’S NOT ABOUT RACE, I SAY. I HAVE NEVER BEEN FULLY HUMAN. IT’S NOT ABOUT RACE. IT’S NOT ABOUT RACE. I CAN’T TALK ABOUT THIS.]

When I read about rapes before, in personal narratives or local news reports, I was always astonished at how often these girls knew their assailants. How they continued to go to parties, to share hallways or bathrooms or lives. Why didn’t they say anything? How could they go on like that?

But I didn’t say anything, either. I let my rapist drive me home.

Having divulged this part of my history: am I more sympathetic as a survivor now? Or am I merely proof promiscuous girls will eventually earn their place?

It has been several months since I was raped. I use the word gingerly. As I write this, I am the most in-love I have ever been in my short and hectic life. I have been needy and scared and anxious and clingy. I have been monstrous. This is because I do not know what love is or how it looks. I walk around it. I observe it and wonder if it will ever be mine.

When I told an ex of mine that I had been sexually assaulted, he said to me, “No wonder you’re into all that weird stuff.” I asked him what he meant by that. He said that every girl he knew who was kinky had been kind of fucked up. I asked whether he’d considered maybe every girl was kind of fucked up.

He didn’t have anything to say about that.

I like weird stuff. I like being a little hurt. It turns me on when men pull my hair back or when they grab my throat. I don’t think it has anything to do with being fucked up. Or maybe it does. Maybe it’s about control. Maybe it’s about the exchange of power.

I used to sleep with a guy; he was big, ex-crew, probably six-four. A real American boy. Blonde curls. He liked being tied up. I couldn’t get over it — it was pretty, my red rope on his skin. But I wanted it the other way. I didn’t want to be dominant. I spent the rest of my life asserting myself, I wanted none of it in bed.

The person I ever loved most — once, he handcuffed me. It was a drunk night and we were happy. And I got on my knees with my hands behind my back. And he guided me, gently, the way my head moved, his hand in my hair. And I felt so safe there on the very edge of my self.

What I’m trying to tell you is that the weird stuff isn’t because I’m fucked up.

Or maybe it is.

I’m trying to say, it’s not bad. I’m trying to say, don’t tell me I’m damaged. I’m trying to say we are all collections of our traumas and that all these things can coexist. The rape and the love and the rough.

I saw him, the man who raped me, at a place where I knew he probably would be. This is vague to protect his privacy, though I’m not sure why; I suppose because he doesn’t know he raped me. I am feeling complicit again.

I looked at him and felt a little sick. Then I felt nothing. I wasn’t there to see him; he was an accessory, another thing in my life the way the rape was also just another thing in my life, another way I had been violated; but who makes a list of violations when she knows it could go on and on and on?

I ran into him at a coffee shop later and — startled — I said, “Hi!” He didn’t say anything. He looked like he’d seen a ghost. Maybe he realized then he’d killed a part of me that night. I suspect he’s aware he wronged me somehow but I don’t know how much he knows.

I think about what happened that night and float outside of myself. I still don’t feel particularly lovable. I wonder if not being lovable is what got me in that fix in the first place, if lovable girls don’t get raped. (They do.) I wonder if this is what happens when you don’t play by the rules. People say there are no rules anymore, but there are, sort of. It’s a different kind of respectability politics, a different kind of acceptable harm, a different kind of ownership of the action and the reception, the doer and the deed.

I don’t know when I’ll stop thinking it was my fault.

Almost a year out I think about damage. I think about harm. I think about how quickly someone can pass through your life and hurt you and carry on. I think about how long I’ve been healing, how very long it will take to feel [good, worthy, deserving, inherently lovable], and meanwhile I’ll keep doing things that might hurt me and meanwhile I’ll keep existing as a tight bundle of contradictions. And it has to be okay.

There’s no point to this. I just needed to write it. I needed to feel my way through this, unpin the responsibility, put it different places, pull apart the guilt. I needed to know where this came from, where the pain went and how the pieces work. It’s bigger than me. It goes back for longer than I have words for. I’m trying not to apologize. But in apologizing, I show my hand. It’s important you see that too.

Larissa Pham is a writer and artist based in Brooklyn.

Georgia Webber is a comics artist living in Toronto, where she is the Comics Editor for carte blanche and the Guest Services Coordinator for the Toronto Comic Arts Festival. She is most often making work about her vocal disability. Georgia wants you to consider your voice. See how at georgiasdumbproject.com.