My Queer-oes: On Young Queer Characters in Comics

by Ashley Gallagher

Recently, comics creator and champion of women comic book shop employees, Kate Leth, tweeted her gratitude that her publisher, BOOM! Studios, allows her to “push her gay agenda a lil.” A couple months prior to that, she’d written in her biweekly comics column about the pushback creators often get from their publishers and editors, nixing queer characters for fear of losing money, or simply out of a personal belief that queer stories are too adult or inappropriate for young readers.

Leth argues that if the straight romances densely populating youth media aren’t inherently sexual or inappropriate, neither are queer ones; furthermore, queer youth have the right to see and recognize representations of themselves in their media, to know that they’re not alone, and that it’s okay and normal and even great to be who they are. I know from experience that she’s right, that it is important for young queer kids to see these representations, not simply for affirmation of a confirmed, existing identity, but also, occasionally, to bring that identity to light.

I’m bisexual. I’ve always been bisexual, but I’ve only identified privately as such in some form or another — bouncing between labels like queer and pansexual until recently settling on bi, for reasons that I’ll save for another day — for about three years. (At the time I’m presently writing this, I still haven’t come out to my parents. Hopefully that will no longer be true by the time this is published.)

Why did it take me so long to figure it out? There are the cliché reasons, of course: growing up Catholic, with its attendant guilt and shame over even the most mundane human experiences, sure didn’t help. Subtle homophobic attitudes dispensed by family members, and not-so-subtle bi-antagonistic myths dispensed by straight and gay peers alike regarding girls who are confused, fake, attention-seeking, experimenting, or simply slutty, are certainly just as likely contributing factors. I was honestly afraid of sex for most, if not all, of my adolescence, and so never had the seemingly universal experience of surreptitiously seeking out and exploring the landscape of my desire through pornography. But there is also the significant fact that my attraction to boys was supported, confirmed, and described by literally every form of media I voraciously consumed, for as long as I can remember. My particular flavor of queerness, on the other hand, simply did not exist, as far as the makers of the worlds I inhabited were concerned.

It’s not that I didn’t know that gay people existed. I can’t nail down exactly when I discovered queerness; maybe, being queer myself, I just always found its existence to be self-evident. And it’s not that there wasn’t any queer representation in my chosen escapist delivery systems, either, simply that there wasn’t enough, and sometimes not quite the right kind. As Leth mentions in her column, queer girls of my generation had Willow and Tara, and Sailors Neptune and Uranus (if you went beyond the censored American release which rewrote them as cousins).

But while I loved Buffy and Sailor Moon, and have a special fondness for those couples, it’s a sort of retroactive pride. During the formative years when I could have desperately used some solid queer role models, the subtleties and realities of their queerness were made invisible to me. Willow and Tara’s romance, for example, blossomed in coincidence with their magical growth, a metaphor that was a little too discreet for my teenage mind to grasp until their relationship was made more obvious. As lovely and powerful as that metaphor was, it’s an example of the peculiar creativity that flourishes under censorship, necessitated by the network’s stipulation that the couple would not be allowed to kiss onscreen. Later in the series, well into her relationship with Tara and long after coming out to her friends, Willow attempts to dispel any suspicions that she might lure Xander, her life-long best friend and former crush, away from his girlfriend by heartily declaring, “Hello, gay now!”, spectacularly undermining in two fell words her long-standing relationship with her first boyfriend, Oz, as well as her old feelings for Xander.

To be clear, everyone is allowed to identify however they want, whether they are actual or fictional people, and there are plenty of lesbian-identified women who have had sexual and/or romantic relationships with men. But Willow was one of the very few fictional characters I knew and identified with who had loved men and women; her vocal detachment from any former desire for men as soon as she “switched teams” only served to indoctrinate me further in the idea that male-facing desire in a woman-liking woman was just an illusion, or part of a transition to a purer gay state of being.

The possibilities presented by the comics I read as a teenager were just as narrow: only two of them had any queer characters at all, one of which was, coincidentally, Sailor Moon. Here was the rapport between Sailor Uranus and Sailor Neptune in its full, uncensored lesbian glory, and I ate it right up. Despite our many differences — I loved and excelled at school, she did not; she was blonde-haired, blue-eyed, cute as hell and involved with a gorgeous older boy, and I was, well, not — I strongly identified with Sailor Moon’s title character. I, like Usagi, nursed a shy, hesitant crush on Haruka, Sailor Uranus’s secret identity. Like Usagi, I chalked those feelings up to Haruka’s masculine presentation.

There is a particular scene in Sailor Moon that I’ve never forgotten. In it, Haruka is tilting Usagi’s face up toward her as they talk privately together. Usagi’s eyes are wide open, her lips softly parting, and she asks Haruka if she’s a man or a woman. Haruka moves her face closer to Usagi’s and replies, now dangerously within kissing range, “Man, woman…Why should something like that matter?”

If Haruka’s face had been turned outward toward her reader, addressing her gaze and her question directly at me, it could not have affected me more. Takeuchi’s art style as it is — with its prominent close-ups of shining eyes and flushed cheeks; the lingering silhouettes of faces intimately juxtaposed, hands gently resting on each other and on the smalls of backs; accentuated with the onomatopoeia of Usagi’s heart beating “ba-dum, ba-dum,” — invites me into the moment to experience it as Usagi does, feeling a desire she never knew she could have, let alone want. This passage is indelibly printed on my otherwise sketchy memories as a moment that forced me to question my own feelings consciously, maybe for the first time. Reading it again now, it still sends shivers of curiosity and anticipation down my spine. Why did my flesh and blood heart beat as insistently as Usagi’s ink and paper one when witnessing this conversation? Why was I as invested in knowing Haruka’s gender?

When Usagi’s desire lay within the same region on the map as mine, I accepted it — but also, unfortunately, the limiting explanation of it that came labeled on the legend. Even now, with all my hard-earned queer wherewithal, I have a hard time finding the vocabulary to describe my teenage rationalizations. I liked that Haruka looked like a boy, years before I knew the word “butch” as anything other than a synonym for ugly, a word someone could use to criticize my lack of interest in makeup, or my short hair cut. But because I also liked “real boys,” that seemed to me to indicate that I only liked Haruka’s presentation separately from her gender, rather than as a part of it.

At the same time that I was poring over my favorite manga series, Marvel Comics launched Runaways, the story of a group of truants on the run from their super-villain parents, as part of its Tsunami imprint, a series of titles drawn in a pseudo-manga style to capitalize on the popularity of manga with young audiences. To my surprise, I found that reading Runaways as an adult with a queer eye and picky standards was an exercise in managing expectations and tempering satisfaction with disappointment. It’s not that its characters aren’t well-written: I actually have a soft spot for Karolina Dean, a lesbian teen with literal rainbow powers who has a desire to be liked by everyone around her, paired with an occasionally obnoxious why-can’t-we-all-just-get-along attitude that made up a large part of my own teenagerhood. Rather, the circumstances she’s often thrown into are a part of a disappointing pattern of benching queers when their stories become too inconvenient to incorporate into the primary narrative. It’s as though Brian K. Vaughan is trying to flag the character as important, to say, “this isn’t just another disposable fringe queer,” when, in practice, key character-building opportunities are jettisoned in favor of advancing a more action-packed A-plot.

If Karolina suffers from having been swept under the rug during some incredibly important character moments — coming out, rejection, and her first queer relationship — then Xavin, her long-term partner, suffers from being too darn subtle and complex for their writers to resist trying to put their definitive stamp on them. When they first meet, Xavin, presenting as a man, asks Karolina to consent to an engagement that was arranged for them before she was born; when Karolina confesses her attraction to women, Xavin, employing shapeshifting powers, chooses without hesitation to present as a woman to earn Karolina’s love rather than forcing her into anything she doesn’t want. After that, Xavin, quite frankly, puts up with a lot of shit, and it’s hard to watch. The other Runaways frequently call them “he” when they’re in female form, and even lob such slurs as “she-male,” “gender-bender” and “t****y,” and Xavin never calls the team out for it, nor does Karolina often come to Xavin’s defense. While she does insist that the other Runaways use female pronouns for Xavin, it seems to come from a place of wanting Xavin to identify exclusively as female, rather than advocating for Xavin’s right to define their own gender for themself. Xavin themself consistently displays ambivalence toward any gender, changing forms as they see fit, and making it pretty clear that their tendency to present mostly female is for Karolina’s benefit more than their own. That never stopped Xavin’s writers (especially after Brian K. Vaughan’s run) from clumsily trying to pull them resolutely into one gender or another, however — in my mind, probably the most unfair mishandling of a potentially empowering narrative of an underrepresented queer identity in a book as rife with disappointments as victories. Saddest of all, we may never get to see a more deliberately genderqueer Xavin, because while not even death is permanent in comics, Xavin was written out of Runaways with a dire fate so inescapable, they may never return from the fringes of the Marvel universe.

A little after Runaways came Young Avengers, featuring as the emotional core of the team Billy Kaplan and Teddy Altman. Billy and Teddy are a pair of exceptional queer characters in that they were actually created by a queer writer — a rarity, even now — and it shows. Their coming out scene is one of the sweetest and funniest in mainstream comics, and their relationship is enviably strong, if not picture-perfect: like many real-life couples, they are often seeking balance between the forces of love and attraction that draw them together, and the sometimes dizzily off-kilter dynamics of power and license that threaten to force them apart. But most importantly to me, Billy and Teddy are a lot like the friends I had at their age.

As far as queer characters go, adults and, with increasing frequency, teens are sort of safer choices for mainstream publishers to greenlight: any bullshit arguments regarding the “maturity” of queer content or its potential for big gay indoctrination can be dismissed by emphasizing that the intended audiences of these books are old enough to handle it. Fortunately, some creators and editors have been growing bolder, and the past couple of years have given truly young queer readers in the U.S. something to identify with and to look forward to. 2013 gave us Matt Fraction’s run on FF, an all-ages Marvel book that makes history by introducing the first pre-teen trans girl in mainstream comics. Her name is Tong, and she’s one of four orphaned Moloids (a subterranean Earth race) who were cast out of their community for evolving in a way that was too different from the rest of their kind. Drawn in Mike Allred’s beautiful poppy art, she comes out in the sixth issue of the series to an outpouring of love from her siblings and gentle support from her guardians. (Reader, I cry literally every time.) Tong’s story is a lovely standout moment in a book that’s firmly dedicated to showing its readers — kids and adults alike — the inherent value and power of loving unconventional families.

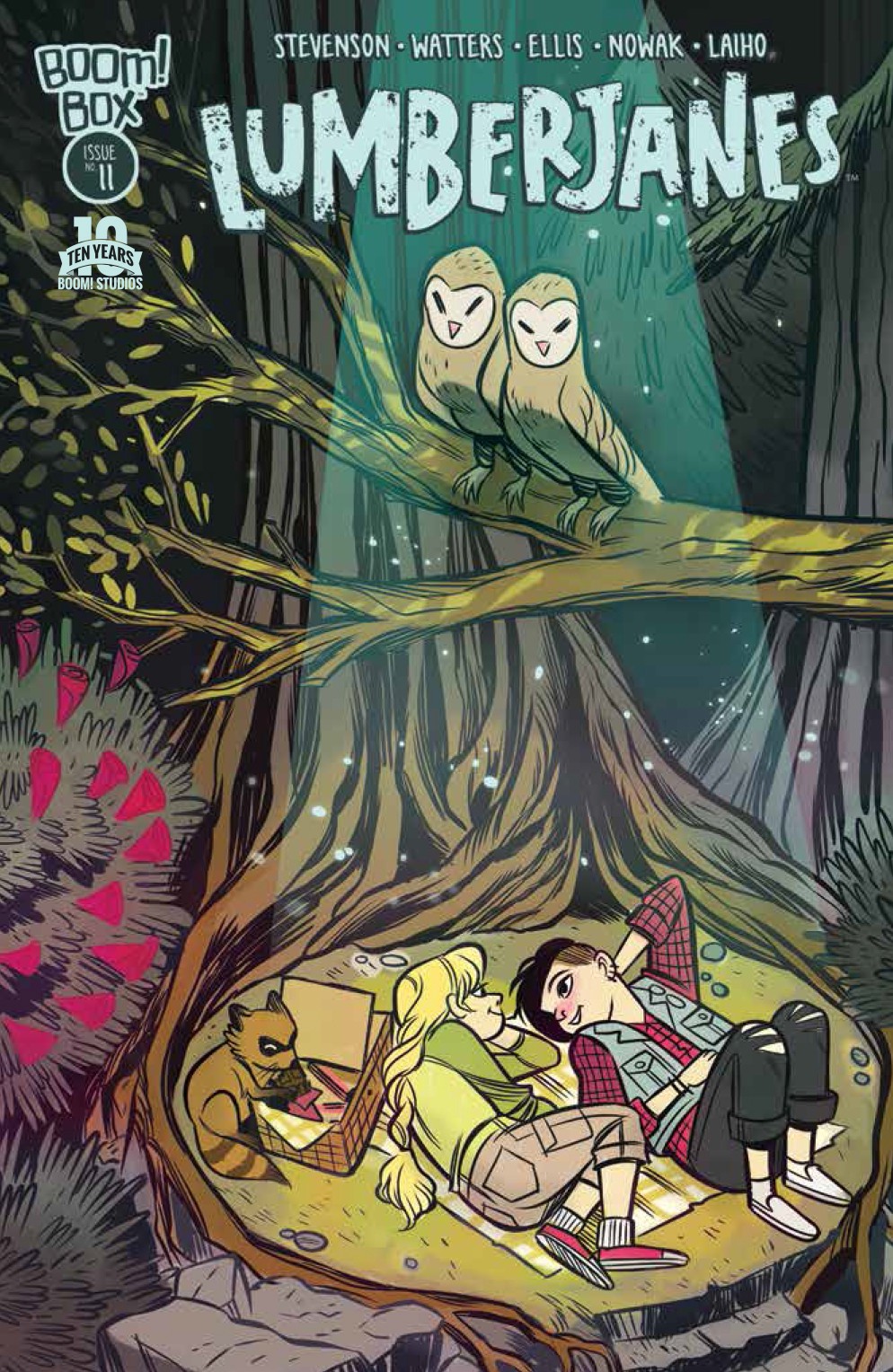

Last year brought us the start of Kate Leth’s aforementioned run with artist Ian McGinty on Bravest Warriors, whose first arc recently wrapped up with Peach, a robotics genius with an electric blue undercut, giving her phone number to Plum, an ancient purple-haired mermaid who seems to have been promoted from occasional Warriors sidekick to full-time team member. Some things you read and imagine they were written just for you, as if Leth had somehow had a vision of and chosen to playfully subvert that time my mother admonished me for having acquired and planned to use a boy’s phone number in elementary school, insisting that girls did not just call boys, and instead had to wait for boys to call them. 2014 was also the year that BOOM! Studios’s experimental indie imprint, BOOM! Box, began publishing Lumberjanes, originally an 8-issue miniseries that has since become an ongoing title. The story centers on group of friends who spend their summer at an all-girls’ camp solving a spooky magical mystery. Two of the Lumberjanes, Molly and Mal, are pretty obviously crushing on one another from the start, and their relationship develops at a steady pace from a cautious friendship to the beginning stages of something significantly more. The first issue of the second arc centers on their first date, complete with a slightly uncomfortable almost-conversation about what’ll happen once the magical summer is over; the following issue’s cover is nothing short of groundbreaking, featuring a heart-achingly sweet tableau of the two girls gazing rosy-cheeked at each other on a picnic blanket in the moonlight. I got emotional just holding Lumberjanes #11 in my hand at the comic book shop, feeling the familiar achy nostalgia for something I never had, daydreaming of the queer butterfly effect that could’ve made growing up bisexual just a hair’s breadth easier with something like this comic in my life.

All of this and more gives me hope that queer all-ages stories are gaining steam and enduring visibility. Over at Autostraddle, Mey Rude wrote about the very queer world of Steven Universe, a Cartoon Network show (and also a comic!) in which it was recently revealed that one character, Garnet, is actually the fused form of two female characters, Ruby and Sapphire, who are very obviously in love and, as alluded to in a musical number and confirmed by one of the show’s writers, in a long-term relationship. Mey also makes mention of a new favorite title of mine, Help Us! Great Warrior, by Madeleine Flores, which features a lumpy heroine who would occasionally rather eat cake and read magazines than save her village, her best friend Leo, a transgender Warrior Woman of color with truly enviable pink hair that sometimes has a mace braided into it, and the newly-introduced Hadiyah, a stylish, hijab-wearing, commanding boss in every sense of the word. Help Us! Great Warrior, originally a webcomic inspired by shoujo manga like Sailor Moon and gag strips like Shin Chan, started as a side project that Flores worked on outside of her day job as an animator. After meeting editor Shannon Watters at an independent comics expo, it got picked up and is now being run as an eight-issue miniseries at — once again — BOOM!, and is reaching a whole new range of readers from the shelves of local comic book shops.

This is by no means an exhaustive history of queers in comics, or even queers in comics that are personally significant to me. (You might have noticed that there’s nary a DC character mentioned here, despite the fact that queers do exist, in some measure, in the DC universe. It’s a personal problem.) It is a sampling of the stuff that was (or would now be) most accessible to me as a middle class suburban kid, and a call for more representation and greater accessibility. While queer characters have come a long way, it’s not enough to have stories populated with a handful of mostly white, cis, able-bodied queers, nor is it even enough to have these characters, skillfully and lovingly written as they often are, in the hands, however capable, of mostly straight creators. What does it take to piece together a self-image that is undistorted and whole, if you’ve only ever seen yourself through a warped mirror?

Stories like Flores’s web-to-print success and the overwhelming fan response to queer narratives in highly visible all-ages media like Steven Universe, Adventure Time, or Legend of Korra demonstrate how desperately this content is needed, and how utterly feasible it is to create it, or facilitate its creation, with the right amount of support. There’s no excuse for lack of access that isn’t simply fear wearing a mask: the world is full of wildly talented queers of all orientations and genders, queers with disabilities, and queers of color who are eager to tell invested listeners their own stories — messy and sweet, full of breaking and healing, like all the best stories — and to share them in their human fullness, without shame. We deserve to carve out a space where our values and experiences can be shared with not just our own children, but anyone, young or old, who needs a gentle shove in a self-knowing, self-forgiving, and self-loving direction.

Ashley Gallagher is a phantom bisexual menace living and writing in Austin. She co-hosts Moon Podcast Power MAKE UP!!, a feminist Sailor Moon Crystal fancast, and complains about men on Twitter.