Fun Palace

by Emily M. Keeler

I grew up in a new place. When I was seven my family bought a brand new house on the North Eastern edge of Calgary. Ours was one of the first ten houses to be finished on our cul de sac. Most of the lots were still unbroken ground, lots of gravel or caked over dirt. I have a vague memory of looking at carpet swatches with my mom — each home was made up of various modular elements, and new home owners could choose cabinet colours and countertops from a limited menu of options. She chose a deep, emerald green for our carpeted floors and stairs, a subdued crème linoleum in the kitchen and bathrooms. We hung brown and beige safari print bed sheets on the tall living room windows, to limit the reflection on our old wooden-boxed TV. Everything we had was a hand-me-down, except for the house itself, so gleaming and new.

I was the oldest kid on the still-forming block. Most of the other families had new babies or toddlers. It was lonely at first, but in a few years I’d reach babysitting age and clean right up.

Two doors down from our house was a twelve-foot crater filled with gravel. It was being shaped to become a basement. I’d play deep down in it, make a little world out of the dirt walls. Getting in was easier than getting out, but I wasn’t afraid of getting dirty, or even of getting hurt. I’d spend afternoons down there, unseen from the street, just crouching at the bottom of a square pit, assuming my divine right as ruler of an imaginary kingdom. The rocks did my bidding, and I bided my time until my mom would step out onto the porch and call my name for dinner. At the sound of her voice I would clamour out of my hole, scale the wall in busted canvas sneakers, and run home to wash the grit off of my stinging red hands, all scraped up from a solid few hours spent as the hard working monarch of my mind’s domain.

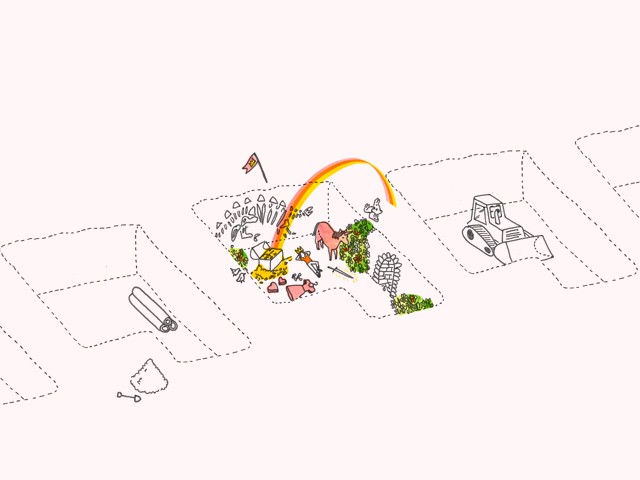

I wrote this essay originally to read for a variety show podcast, the theme of which was “Fun Palace.” In the early 1960s, an architect named Cedric Price and a theatre artist named Joan Littlewood proposed a building that could be a toy, an adaptable space that required its user to partially make it. You can see, perhaps, why I thought of my childhood in the wilderness of flash-built suburbia.

Back then, time, as it still does and always will, passed both far too quickly and in an agonizing trickle. Too soon my pitted paradise was tarred over. My mother wouldn’t let me play on the lot a few doors down after she was forced to make a trip to the hardware store for turpentine; on my last afternoon in the basement-to-be, I was pulling my subjects through the black stuff that construction workers had spread around the dirt to insulate the clean concrete they would soon pour onto the earth. My hands and arms were covered in the half-set sticky goo that smelled, to me, like dragon’s breath. It affixed little pebbles into my palms and I had a hard time climbing up and out. It was the first time I needed someone to rescue me from my own imagination. After she pulled me from the pit, my mom tried to pick the tiny rocks out of my hands, and couldn’t. She soaked my hands in a dish of turpentine. (The memory came flooding back, equally irrepressible and insignificant, 15 years later when I experienced my first ever professional manicure.)

Eventually the basement was filled and my kingdom was gone. By the time I was twelve, the house was built up and Taryn and her four year old son Thor had been living there for a year. Watching Thor was one of my regular babysitting gigs. Considering my preteen expenses (slur-pees, second-hand Harlequins, cute tee shirts from Zellers or the Sally Anne), I was almost staggeringly wealthy with a tax-free income often in excess of $40 per week. In the land of new houses and new families, being the oldest kid on the block rules.

Price’s Fun Palace had one basic lattice work frame, with the idea that rooms and theatres could be quickly built onto it, and just as quickly dismantled. Picture the wooden frames of a half-built house, each plank secured by a fixed metal joint. Now picture my mother, choosing the faux oak cabinets and the creme lino.

So yes, for an adolescent, I was rich beyond belief. And I had a best friend, Billie. I’d buy us both nickel candy and we’d walk around, cinnamon red dye intensifying our mouths. Because the suburb was relatively slow to sell out of lots, we had lots of dirty places to play. We made ourselves at home in houses in every stage of development.

Billie and I used to climb up each other’s backs to get in to finished places through the back door. The construction workers never locked sliding glass exits, and we’d have picnics on the imacculate carpets. Sometimes, Chris and Owen, two boys we’d met at school, would join us, and the four of us would play at adult domesticity in the theatre of an empty den, the dusty tang of drywall still hanging in the air. Once, the four of us shared three cigarettes we’d lit off a brand new electric stove, and two cans of cheap Canadian beer. Billie and I considered this a near-perfect kind of double date. Though I knew they both liked her more than either did me.

Let me set a little bit of context for you. I babysat between eight and ten hours a week from the time I was 11 years old until I was 15. I was usually paid either $4.50 or $5 per hour, though sometimes I wasn’t paid at all. By all standards, I was rich. But the reason I was rich was because I lived in a neighbourhood at the farthest, poorest edge of the city. Single moms could afford to have me watch their kids after school, I was much cheaper than daycare, and they could get in their second shift easy-peasy. The modular houses were cheap to make and cheap to buy. My family lived in the one with the green carpeting for just under nine years, and had to replace the bathroom floor twice because it, like the rest of the house, was made of a fibrous particle board with a severely limited lifespan. New was a luxury, yes. But nothing there was made to last.

Billie and I inevitably played Truth or Dare with Owen and Chris. We’d watch each other take quick showers, without shower curtains or towels. We’d talk about nothing but it would feel dizzying. Once, the three of them locked me in the closet of a master bedroom. Another time, in a house without walls but with appliances, Owen dared Billie to make out with Chris in the bathtub. Billie didn’t say yes, but she didn’t say no. I wrestled with my contradictory feelings of protectiveness and envy. Did Billie actually want to be pinned down in the tub? And why couldn’t I be pretty enough to make boys silly and weird like Billie did?

The next day I biked over to the newest block and leaned my bike against the back wall of a house with fresh yellow siding. I had taken a cigarette from my mother, and a lighter that I’d been practicing for weeks. I also brought an extra t-shirt, because I figured a towel would be too conspicuous. The house was two stories, and it had a mantle but no fire place. The upstairs bathroom was completely done, minus a door, but some of the rooms on the main floor still had plastic sheets where wall would eventually go. I took off my clothes, laid the extra shirt on the toilet lid, and crawled into the tub, where I turned the water on. The plan was to play by myself, but because I was too old to play I would do what my mom did when she wanted to be in her own head; I would take a bath and pull dramatically on a cigarette.

The tap sputtered out a puff of drywall dust and then a trickle of freezing cold water that the whole situation into a sullen grey sludge that had splashed up my legs. I turned the water off, wiped up the mess with my tee shirt, and left. It was not what I’d planned, but nothing had ever felt real in these new houses. Until somebody actively moved in, these places belonged to no one, and nothing real could happen inside. For Billie and me, for Chris and Owen, and who knows how many other neighborhood kids, each lot was 100% potential, and therefore not yet real. So I guess all I’m trying to say is that they were their own kinds of fun palaces, formed and unformed over and over again, a place to see what life feels like before you really start to live it.

Emily M. Keeler survived being a weird teen and now works for a newspaper in Toronto. The radio show she read a version of this on is called, yes, The Fun Palace Radio Variety Show.

Allison Burda and Cam Gee live and work together in Toronto. They post drawings of chubby dogs and other stuff at allisonandcam.tumblr.com.