A Dress To Die For

by Katy Kelleher

With gifts they shall be sent,

Gifts to the bride to spare their banishment,

Fine robings and a carcanet of gold.

Which raiment let her once but take, and fold

About her, a foul death that girl shall die

And all who touch her in her agony.

Such poison shall they drink, my robe and wreath!

Howbeit, of that no more. I gnash my teeth

Thinking on what a path my feet must tread

Thereafter. I shall lay those children dead —

Mine, whom no hand shall steal from me away!

Then, leaving Jason childless, and the day

As night above him, I will go my road

To exile, flying, flying from the blood

Of these my best-beloved, and having wrought

All horror, so but one thing reach me not,

The laugh of them that hate us.

Let it come!

Is it possible to read Medea without getting chills? Long before Taylor Swift faux-dismissed her haters, who are going to hate, hate, hate, Medea gnashed her teeth and shouted to the fates, “Let it come!” Rather than shake it off or preach a milquetoast revenge of living well, she razed her own precious life to the ground. Medea salted the earth and killed her children. She destroyed her cheating husband. And most importantly for this particular article, she murdered her competition with the trappings of royalty. She sent the princess Glauce a golden dress drenched in poison.

Medea was the first Greek play I ever read the whole way through, and that crazy queen has a special place in my heart. When she speaks, anger permeates every sentence; poison seems to seep from the page. Some of the anger is righteous — after all, she was just kicked out of her own home by her husband, Jason, who returns from war with a new, younger girl in tow. But Glauce doesn’t deserve death by dress any more than Medea’s children deserve to be slaughtered.

Medea is not the earliest mention of a poisoned dress in history, but it remains one of the most powerful in Western literature. Similar myths have shown up in ancient Hebrew, India, and modern Europe. According to one Greek myth, Hercules was killed by a poisoned robe that burned his skin and flayed him alive.

Like other narrative arcs that replay over and over in our fairy tales and myths, the poison dress resonates for a reason. Clothing is intended to shelter us, to provide a firm barrier between the squishy stuff of our personhood and the sharp edges of the outside world. Clothing should protect us and shield our nervous parts from the thorns of Eden.

But despite its intended function, clothing is often harmful — particularly to the women who wear it and the workers who make it. Beauty is pain. And it’s a pain that begins far before Glauce tightens the strings on her golden bodice, long before ladies shimmied into their arsenic-laced gowns, long before we stepped into our Forever 21 high heels and stumbled towards the nearest bar. It’s a pain that begins in production.

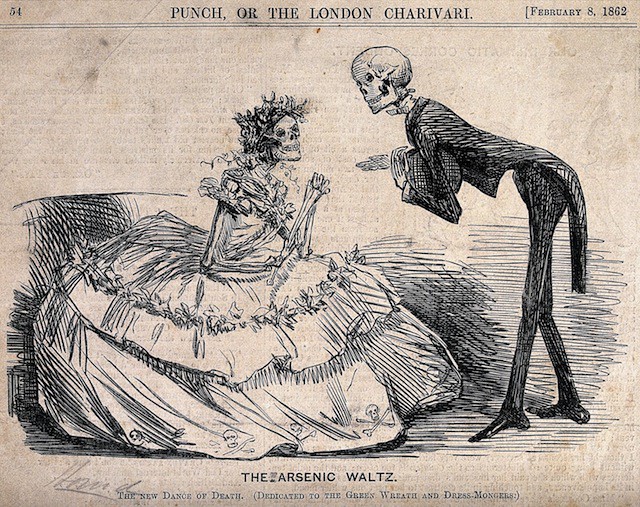

In falling down the rabbit hole of research about the myth of the poisoned dress, I came across an etching titled “The Arsenic Waltz” from 1862. The satirical image shows two skeletons dressed to the nines. The gentleman stands, hat in hand, and offers his other hand to the lady. Her bony torso rises from a big pouf of a gown, as fussy as a cupcake. On her head sits a mess of silk flowers. “The New Dance of Death,” reads the caption.

This morbid cartoon perfectly illustrates the arsenic hysteria of the Victorian age and the hazardous green dye. Magazines of the time frequently lampooned the cultural obsession with the vibrant, rich hue that went by many names, including Paris green, Poison green, Schweinfurt green, and Vienna green. An earlier green, called Scheele green, after its inventor Carl Scheele, was developed in 1775 using arsenic as one of the main chemical components. The color was further refined in the following decades. The yellow tones were scaled back, resulting in a brillianpure green that is now often called “Jungle.” This bright emerald color was used to taint everything from fabric to wallpaper to candles. Even William Morris, the great pattern maker and leader of the Arts and Crafts movement, used arsenic in his wares — in fact, his family owned the largest arsenic mine in England, so you could say all his green was poison green.

“Some have called the nineteenth century ‘The Arsenic Century,’” says Alison Matthews David, an associate professor at the School of Fashion at Ryerson University in Toronto. In 2014, David worked alongside Bata Shoe Museum Senior Curator Elizabeth Semmelhack to create the exhibition Fashion Victims: The Pleasures and Perils of Dress in the 19th Century. According to David, arsenic-laced dyes were used in the production of many goods, not all of them gendered. However, “the rhetoric is always directed against the women wearing these dresses and shoes,” she says. “Why did they persist in wearing it? But if you were a middle-class or upper-class woman, you were expected to wear it.” If you find this double bind completely shocking, then perhaps you haven’t been paying attention to women’s fashion and the conversation surrounding it, like, ever.

Although the Victorian media focused on warning men about the risks of dancing (and other, less vertically inclined things) with these femme fatales, the real danger wasn’t in wearing or touching the fashionable items. Sure, you might get an unsightly rash from wearing a dress dyed with arsenic. You might even wind up inhaling small amounts of it. But this was nothing compared to what the seamstresses suffered. “As they ripped green fabric apart, they would inhale everything that came off it,” explains David. She refers to the case of a 19-year-old silk flower maker in London who was killed by her exposure to the poison. “Arsenic can cause skin cancer, among other problems. The things they were working with had long-term effects. Conditions were just horrific.”

While fine ladies suffered from rashes, the women who made these dresses were in for something much worse. Arsenic poisoning begins with headaches, confusion, and diarrhea, and ends with comas and death. In between, you’re likely to experience a number of unpleasant things, including hair loss, bloody urine, convulsions, cramps, liver disease, and lots and lots of digestive problems. It is not a pretty way to die.

“Girl wears new formal gown to dance. Several times during the evening she feels faint, has escort take her outside for fresh air. Finally she becomes really ill, dies in the restroom. Investigation reveals that the dress has been the cause of her death. It had been used as the funeral dress for a young girl; it had been removed from the corpse before burial and returned to the store. The formaldehyde which the dress has absorbed from the corpse enters the pores of the dancing girl.”

— The Encyclopedia of Urban Legends by Jan Harold Brunvand

While poisoned garments were an actual problem of the Victorian age, the myth of the poisoned dress that kills its wearer is most likely just that — a myth. David and her colleagues haven’t found any solid evidence of death by gown, and yet this idea persists. It appeared in the 1998 movie Elizabeth, in which a handmaiden was killed by a gown intended for the queen (a completely fabricated bit of drama). The Encyclopedia of Urban Legends calls “The Poison Dress” or “Embalmed Alive” one of the earliest urban legends noted by American folklorists. Often, the story would include references to a specific department store where the dead girl supposedly purchased her dress. Some believe that the story was circulated by stores looking to discredit their rivals, an early form of particularly virulent viral marketing.

In researching the case of the poisoned dress, I was struck over and over by the repetitive nature of our fashion woes. It’s been hundreds of years, and yet we’re still blaming the fashion victim for the hurts her clothes cause. We’re still buying clothes that are made by workers in conditions that can be accurately called “horrific.” We’re still consumed by a desire to be pretty. To wear the right colors and own the right things. At least, I am.

I said at the beginning of this piece that the myth persists because the poison dresses betray the very concept of clothing. But perhaps the reason it sticks in my gut is because of something even more threatening than the familiar perverted, because that’s what the poison gown is — a familiar object made unfamiliar by unseen forces. Maybe this myth — and occasional reality — doesn’t matter to modern readers because it illuminates a primal fear or despicable betrayal. Maybe the takeaway isn’t that that arsenic is fascinating (though it is) or that Medea is kind of awesome (which she is). Maybe the more important point is this: we can’t have nice things, not really. Not without some consequence. Not without paying a higher price.

Katy Kelleher is a writer living in Portland, Maine. She is currently collecting ghost stories. Have a good one? Email her at [email protected].