Looking The Part

A few months ago a friend of mine contacted me about doing a project together, saying she wanted to write with more “women of color.” I didn’t know whether to correct her or not. Are you allowed that title when your color fades?

I am not white. It has taken me years to be able to say this out loud, and I still mumble through it, or qualify it with “sort of”s and “basically”s and “not really’s.” Because despite my Indian immigrant father and my non-white name and my ability to do the sideways head nod gesture that seems to only be a thing Indians can do, I have rarely been treated as anything but white and American.

When I first began understanding the realities that many people of color in this country face, I aimed to become an ally. It made more sense than considering myself part of the group, since I assumed the title of “person of color” had to come with certain things: namely, a struggle stemming from a lifetime of mistreatment and microaggressions. I mistakenly associated the POC identity with its most publicized experience, one which I didn’t think I shared: I’d always made friends of lots of different backgrounds, and sometimes we talked about them and most of the time we didn’t; I had no problem seeing myself in the white protagonists that saturated the media I consumed. But the biggest misconception I had was that to be “of color,” my skin actually had to be one, and that it had to stay that way all the time.

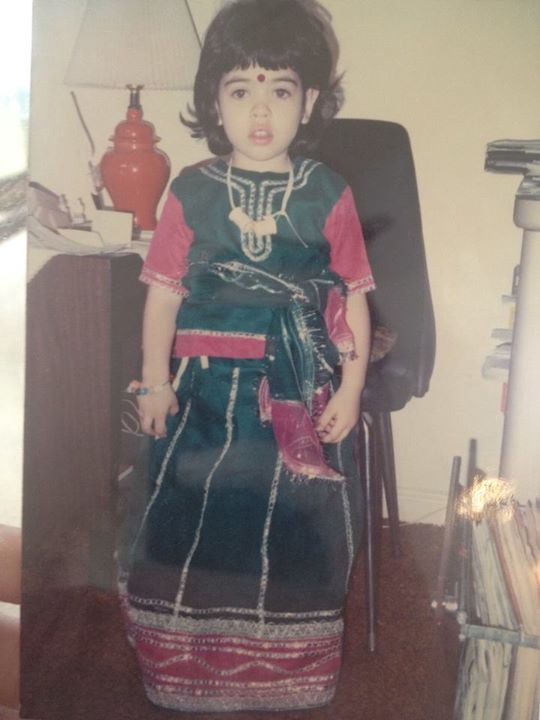

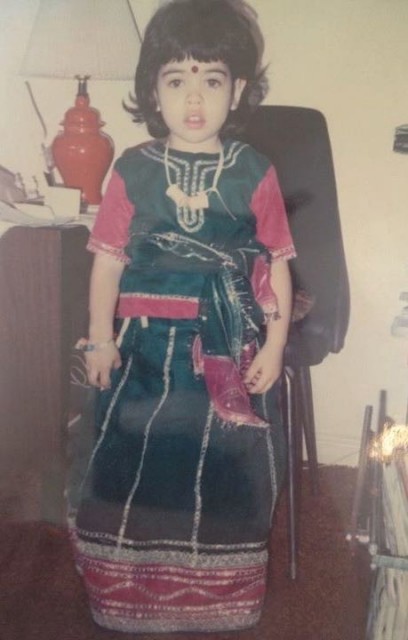

When I was a kid, I assumed my “natural” skin color was a deep tan. Maybe it’s because summer is when most photos of me were taken, on the beach with my white cousins, them in brimmed hats with freckles and flecks of sunblock still on their skin, me wild-haired and brown brown brown, always exposed. I worked backwards from these shots, using them as yearly proof of what I “really” looked like — thick black hair, big eyes, a flash of beauty I hoped would become permanent by aging out of frizzy bangs and overall shorts, and brown skin.

In a grade school worksheet I was asked to describe myself, a quick lesson in bodily features, and I dutifully took these images to write my truths. “My name is Jaya Saxena. I am eight years old. I have black hair. I have hazel eyes. I have brown skin. My favorite color is red.” They were natural statements to make, things that there’d be no point fabricating. But in the winter I’d find myself staring confusedly at my reflection, wondering where one of those truths went, and what happened to my “natural” state.

My family is full of stories of how nobody thought I “belonged” to either my mom or my dad when I was a baby — -there was either confusion over why my dad had a white child, or assumption my mom was an Irish nanny. “Where’d you get her?” became a common question. But as I grew up it became clear that the genes were strong on my mom’s side. I’ve inherited her hourglass figure, the slope of her nose, the big toe that pops through the tops of shoes, and, as I started to learn, skin that turns paler than you may have thought possible from someone with an Indian father.

It is his genes that cause my tan to come quickly and powerfully, blooming across my body the moment there is sun and warmth, restoring order. I’ll run errands on the first bright spring day and end up with my face a shade darker, my arms and legs following as soon as I can ditch a jacket. Those are the days “of color” starts to sound like it fits. It holds on as long as it can, until early November maybe, until one day I look in the mirror and the natural dark circles under my eyes look ghastly, and my black hair seems too-heavy and goth. I am literally drained of color, like I’m missing something. When my tan fades, no one would think to question my whiteness. Parts of me become entirely too easy to erase.

The first time I saw an ad for Fair & Lovely skin lightening cream I was sitting on a hotel bed in India. I was thirteen years old, waiting for my grandparents to tell me it was time to get ready and visit all the family we had come to see. I didn’t understand why anyone would want to use it, a testament to my naivete about colonialism, beauty standards, and the persistence of the idea that darker skin is culturally undesirable. It was December, and these women were promising a way to achieve my faded skin color as I coveted theirs. Later I saw a bottle in a relative’s bathroom.

Then, I didn’t know that being dark could be dangerous. I didn’t know about “othering.” I didn’t know how my dad was harassed when he first came to America, or how different and unwanted my family was often made to feel, or how many assumed he and my mom married for a green card. I just knew I craved my summer skin. That skin made me look worthy of my name and the bindis my grandmother would stick to my face.

The eternal gaslighting of “social colorblindness” tells me my skin color should not matter to me or anyone else, that all it does is label us. It’s a well-meaning theory, and something I thought I wanted for a long time. I spent years thoroughly enjoying being ethnically ambiguous, and sometimes when I’m drunk and a particularly clueless guy is hitting on me, I still enjoy making him play the “Where do you think I’m from?” game. But not once has he ever mistaken me for what I am. Losing a tan does not change my upbringing, and I am no more or less Indian or American or New Yorker because some melanin gets triggered. It should be nobody’s business what my ethnic makeup is, anyway.

And yet, there is something freeing about looking the part. I don’t want to be another white woman who decided bindis were cute.

From some, there has been the expectation that I should be grateful for my genetic outcome. “You’re so lucky you’re fair, you just look ‘exotic,’” I’ve heard from misguided friends and family, white and Indian alike. I get asked about “passing,” which either assumes that I am trying to look the way I look, or that I am ashamed of my background, and that any of this can be explained beyond “genetic lottery.” Or I become privy to conversations people would not have in front of me if they knew my background, complaints about smelly cab drivers and disgusting food.

Unlike many in my situation who have fantasized about waking up with pale, freckled skin and blond hair, the frustrations and confusions only made me miss my color more. Summers are the only time I am recognized for this other aspect of myself. Whatever issues that brings (the endless “no, but where are you from?” questions), I feel whole. There is an outward sign of my identity that lets everything else fall into place.

Recently, I have found solace in bronzer, a tool that most white women use to achieve a coveted, but false, tan. I guess I use it the same way. I can’t speak for them, but the first time I tried it it felt restorative. It takes them farther from their “natural” selves, but it gets me back to normal. I worried it was too obvious and too dangerous, like I was making up for my lack of color by applying some sort of shimmering brownface, but when I confessed this to a friend, they told me that if it makes me feel like more of myself, then it’s doing its job.

I am learning that my mistake is in assuming that an identity has to include certain markers or experiences; yet visibility, the literal kind where people look at you and have an idea of who you are, is the most powerful tool. If signs of my heritage can be erased so quickly — with a flat iron or some hair dye or a few months of winter — and put back in place just as fast, they are obviously not the core of my identity. But, man. That can be easy to forget. I am not the first well-meaning ally to mistake the trees for the forest.

Right now it is February, and I do not look the part. I’m trying to remember that I don’t have to.

Jaya Saxena is writer and professional Prince impersonator.