From Samplers To Antlers: A Brief History Of Human Hair Art

by Katy Kelleher

“For children, no art or accomplishment is more useful than the ability to make articles of tasteful ornament in Hair Work. This will open to all such persons a path agreeable and profitable occupation.”

— Mark Campbell, 1867, from his book “Self-Instructor in the Art of Hair Work”

Human hair is a funny, complex, beautiful, ugly thing. When it’s attached to a head, people have no problem touching it. But once it’s removed from its source it becomes at best a nuisance for vacuum cleaners and at worst a viscerally repulsive object that causes waitresses to lose their tips and diners to lose their shit. In the past few months, I learned that hair art creates a similar divide. After spending an afternoon in the historic Skolfield-Whitter House in Brunswick, Maine, I excitedly showed a few pictures of the intricate hair wreath to friends I was meeting for lunch. “That’s disgusting,” said Emily quickly. “Oh my god, I want to eat it,” said Jaed just as quickly.

He was joking, but I get it. That piece, in particular, was stunning. Made by Ms. Clara B. Kennedy in 1868, the wreath is constructed of human hair in a variety of shades, dyed and natural, supported by a system of wires and accessorized with shiny glass beads. When you move it, springs bounce and wiggle like antennae. Near the top, a few hairs are artfully left unbraided and stick out straight; I imagine they’re supposed to look like wild grasses. The entire piece is so tactile and lovely in a strange, creepy way. Not just inanimate, it’s dead, made from so, so many dead cells. It’s also weirdly alive in a way that most objects are not. I had to handle all the pieces of hair work with white kid gloves (literally) and as soon as the museum official left the room, I fought the urge to rip off my gloves and stroke the shiny blond bow. I didn’t want to eat it, but I definitely wanted to feel it — even though hair art in person looks pretty fuzzy and gross. Deep down, I find that weird combination of desire and repulsion to be the most interesting of all emotions.

When it comes to hair, the repulsion part of the equation is relatively modern. During the Victorian era, jewelry made with human hair was commonplace, used for both mourning lost loved ones and sealing a friendship. It was also a way for middle and upper class women to show off their dexterous decorative skills. These were the same ladies who learned embroidery, piano, painting, and the vocal arts and could perform them all on cue. Why not add weaving impossibly tiny flowers out of your dead husband’s hair to the roster?

Hair art, like nearly all forms of worn expression, was deeply tied to status as well as issues of race. Hair jewelry was worn by middle class Americans of all ages and genders and it was very much a white people thing. While some black women during the Civil War era worked as hair artists, their clients were white and the hair they used typically came out of white scalps.

It was very much in keeping with the sensibility and sentimentality of the time. Of course, those words meant something quite different back then: “Swooning while hearing bad news was to be ‘sensible,’ that is, overwhelmed by one’s senses; weeping while telling the story about hearing the bad news to others (for the fifteenth time) was to be sentimental,” writes Helen Sheumaker in her book Love Entwined: The Curious History of Hairwork in America, a book that functions as a roadmap for my obsessive research of the topic. It was a sign of your class, your delicacy, and your refinement to show off your sentimental side. Even the simplest ring, watchband, or button made from hair could act as a little beacon, calling out to the world: I feel! I feel strongly. Oh, and by the way, I’m also rich.

“This lock of hair once did grow.

Upon a persons head you know,

But now is placed within this book

For those to see that may chance to look.”

— Harry Egy, 1850s, quoted in Love Entwined: The Curious History of Hairwork in America.

According to Leila Cohoon, a retired hairdresser and owner of Leila’s Hair Museum, examples of this unusual art form has been traced back as far as the 12th century. The oldest piece in her collection, which features over 2,000 items, is a broach labeled 1680. Located in Independence, Missouri, Leila’s Hair Museum is frequently listed on travel sites as an American oddity alongside tacky talking Paul Bunyan statues and the World’s Largest Ball of Twine.

But like all those sights, Leila’s collection can tell us a lot about North American culture and history. While the pieces date back to the Colonial Period, most of her collection is from the heyday of hair art. Hair art had been popular in Sweden for a while, but two important British deaths served to spark the trend in America: Princess Victoria and Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s mother and husband. Queen Victoria is widely credited as starting the whole hair art craze. After these royal family members died, she went into a prolonged mourning period, which lasted until she popped her clogs in 1901. According to some accounts, Queen Victoria always wore a piece of jewelry made with Albert’s hair or a heat-shaped locket containing one of his locks. The zeal with which she applied herself to mourning became famous, as did her macabre black silk fashions. In the 1860s hair art officially became A Thing, popular in the United States, Canada, the UK, and Europe — wherever fancy white people were hanging out, one could also find braided loops of hair attached to watches or woven patterns shining dully from buttons.

There are many boring, small pieces of hairwork floating around. Rings made of hair were common gifts between girls (ye olden BFF necklace). School aged children often kept books of hair from their peers, and men wore hairy tokens from their lovers in the form of a watch chain or a pin.

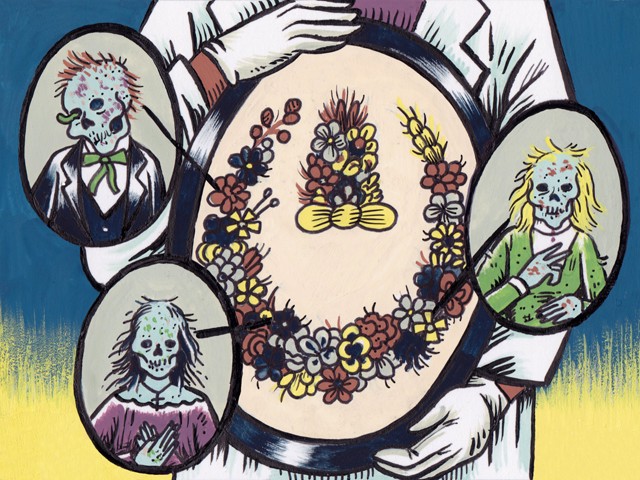

These are all well and good, but I am particularly interested in two kinds of hair art: wreaths and mourning jewelry. Wreaths are fascinating simply because of the scale. With the wire center, it was possible to create large-scale works out of a small amount of hair. They also had enough structure that the artist could really go all out. They often featured flowers, and in the Victorian era, flowers were considered deeply symbolic. If speak fluent floral, you can “read” each wreath for its purpose (field daisies meant innocence, while dandelions meant coquetry).

Mourning jewelry also has some fascinating iconography. These pieces often featured images of tombs, skeletons, weeping willows, weeping ladies, lilies, and other symbols of sad times and recent death. Mourning jewelry became particularly significant after the Civil War. In the 1870s, several companies sprung up that would attempt to commercialize hair work. You could send in the hair of a dead loved one, and receive a piece of jewelry months later. While these pieces were still made by hand — and hair art really needs to be made by hand — some places cautioned that the mourner might get a memento that featured hair from… someone else. And that really defeated the entire purpose, didn’t it?

The other thing that makes mourning jewelry so compelling is the richness of its symbolism. According to historian Geoffrey Batchen, “hair, intimate and yet easily removed, is a convenient and pliable stand-in for the body of the missing, memorialized subject.” One small part of the body comes to stand for the whole (which by the point the hair art was completed was probably well on its way to total decomposition). Unlike the bacteria-filled, bloat-prone messy corpse, hair art could last for a very long time, if properly cared for. Before it was woven, was cleaned and treated, and then plaited tightly to prevent flyaway strands. Hair jewelry was often preserved behind glass or kept inside a locket. Each piece was viewed as a direct connection to that person, a truly intimate remembrance.

Wreaths tended to play a slightly different role in mourning, one that was privately displayed rather than publicly worn — private being relative here, since sentimentality needs an audience to be performed correctly. Wreaths were so intricate, and required so much hair, that it took multiple heads to get it all done. Like much of the jewelry, wreaths often served a funereal purpose. Here is a description from the Victorian Hair Artists Guild, a group of women that are still practicing the art today:

Most of the hair wreaths were formed into a horseshoe shaped wreath that was placed on a silk or velvet background inside the frame. When memorial wreaths were made, hair was collected from the deceased and added to the wreath whenever any one died. The top of the wreath was always kept open at the top….ascending heavenward. It is said that the newest addition would be placed in the center, and then moved to the side to become part of the large wreath when the next person passed away.

I’m just imagining some particularly obsessive hair artisan (perhaps a child, like Mr. Campbell suggests) just waiting around for her red-headed sister to die so she can finally make that rose she’s been dreaming of. Eventually, she takes matters into her own hands. For more hair-raising horror, check out Pauline C. Smith, a horror writer from the 1960s who actually did write about a murderous hair-braider in A Flower in Her Hair.

“When attached to the body, we praise hair and teeth that adhere to the rules. They are key sites where body beauty is defined.”

— Polly van der Glas, Jewelry maker & artist

The official death of hair art in America occurred in 1925, when most major jewelry companies stopped offering hair jewelry repairs or custom work. For the most part, hair art was quickly forgotten, remembered only as an oddity of the past. Interest was revived briefly in the 1960s and 1970s, when all things crafty were being brought to the forefront as feminists reassessed the value of so-called “women’s work.” It didn’t take off.

There are a few devoted practitioners of Victorian art today, most of which can be found online. If you’re the DIY type, the Museum of Mourning Art in Virginia offers classes on hair work. And if you need materials, a sprightly little trade in human hair and hair works has sprung up on ebay and other sites. HairWork.com has a nice selection of human hair for sale. One poster, who is selling 16 to 20 inches of “virgin blond hair,” asserts that she will “not cut my hair until I receive payment.” She accepts Paypal.

Contemporary artists have also turned to hair as both a source of inspiration and a new medium for their work. Melbourne jewelry artist Polly van der Glas makes strangely beautiful pieces from human teeth and hair that she sells in boutiques and on Etsy. Jenine Shereos creates amazingly perfect leaves from stitched hair, and Nagi Noda has become famous for her “hair hats.” Using hair that’s still on the head, the music video director sculpts truly awesome animal shapes, like foxes, rhinos, and even an antlered elk. Kerry Howley, a UK-based sculptor, makes hair jewelry that uses similar techniques as her Victorian forerunners but is far less wearable than their work. Howley’s are fantastic though, and beautiful in their own strange and delicate way. Notably, all the artists I’ve found that are working with hair are women. There are plenty of male artists who have worked with bodily remains (like Dash Snow and his semen splats) but long, twisty strands still haven’t lost their feminine connotations — on or off the head.

Thanks to the Prejepscot Historical Society for letting me touch their hair and aiding in my research.

Katy Kelleher is a writer living in Portland, Maine. She is currently collecting ghost stories. Have a good one? Email her at [email protected].

Lauren Kolesinskas is an illustrator and tattooer living in Brooklyn. Her most commonly used words are ‘butts’ and ‘garbage’.