Apotropaic Boners; or, How to Avoid the Evil Eye

by Anna Rasche

Mandy Len Catron recently wrote an article for the New York Times entitled “To Fall in Love With Anyone, Do This.” After following a long formula laid out by the psychologist Arthur Aron, the last step was to “stare silently into each other’s eyes for four minutes.” Mandy and her partner are now successfully in love.

Intense eye contact as the pathway to a lasting romance isn’t a new realization. The ancient Greek novelist, Heliodorus, wrote “The origin of love…owes its first beginnings to sight, which strikes its passion into the soul.”

But to Heliodorus and his classical contemporaries, an intense gaze was just as likely to bring about pain and misfortune as true love. I’m talking, of course, about the Evil Eye.

Belief in the Evil Eye is the belief that certain individuals possess a supernatural ability to cause real physical harm through an ill-meaning glance. The Eye is always envious of those with better fortunes than itself, so those who find themselves in lucky circumstances are especially vulnerable to its gaze. The Evil Eye may be cast purposefully or by accident. It is not always possible to determine who holds the power of the eye, and sometimes the possessors themselves are unaware (which is scary).

Though a powerful and persistent superstition throughout much of the old world, the ancient Romans and their Italian descendants were particularly aware of the Eye’s presence. It is called the malocchio, and the possessor a jettatore on the peninsula. The dastardly effects (which range from mildly annoying to…well, evil) were thoroughly described by Giuseppe Pitre in 1889:

“If you have to speak or sing at a public gathering, all of a sudden you lose your voice or, if it’s at night, the lights go out; a window opens and your papers are either messed up or blown away…If you are in love and your love is returned, the jettatore can easily cool your girl’s passion. If you depend on a friend for some important business, you can be sure he’ll get sick just the day you need him while until yesterday he was ready to help out…A storekeeper…will begin to notice customers avoiding his shop. A child, under the influence of an occult and inexplicable illness, will begin to waste away.”

Naturally, this ever-present threat of invisible evil weighed heavily on the minds of believers, and protection was sought in many forms. For the ancient Romans, one of the more potent defenses against the Evil Eye was to distract it with amulets shaped like boners. For example, see the below pendant, which dates back to the 1st century A.D.

Or this one:

Or this carved gemstone:

According to Pliny the Elder, amulets featuring phalluses were worn by everyone from military generals to little babies. These two demographics in particular were thought to be popular targets for the Evil Eye, because in ancient Rome everyone was jealous of successful generals and families with babies that didn’t die. The ancient gold ring below measures only 1.3 cm across and was likely worn by a child.

So why did the Romans choose to entrust their health, wealth, and well-being to disembodied penises?

Well, an impressive phallus was the chosen manifestation of the god Fascinus, a protector deity whose worship was entrusted to the vestal virgins. The word “fascinate” derives from his name. In ancient times, it was believed that by distracting the Evil Eye with sexually explicit imagery, it would become “fascinated” and forget to look your way. Plutarch recorded that “the strange look of (amulets) attracts the gaze, so (the Eye) exerts less pressure upon its victim.” In other words, the Evil Eye is a dick, so the best way to fight it is with more dicks.

The Romans didn’t just stick to boring old regular phalluses. They had all sorts of creative variations, which are perhaps best represented in artifacts known as tintinnabulum:

These imaginative penis-themed wind chimes were hung outside of entryways to protect the whole dwelling from the Eye. They often have wings, and sometimes small figures are perched triumphantly on top. As you can see from the above examples, tintinnabulum get pretty meta, sometimes featuring an anthropomorphic dick with a dick of its very own and a suspiciously dick-like tail. It’s three times the evil-fighting dick power in one object!

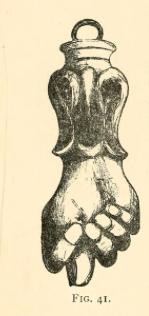

Also showing up with frequency in the archeological record are apotropaic pendants carved as the mano fico, which is a saucy hand gesture representing a phallus inserted into a woman’s “fig,” as the Romans liked to call it. VERY distracting for evil eyes.

The mano fico symbol has remained a popular amulet and good luck charm through modern times, its obscene meaning being a bit more subtle than that of a penis with wings. Even during the famously prudish Victorian era, the author of the above illustration noted in 1895 that “the fist with protruding thumb is to-day one of the commonest of objects worn as a charm for the watch chain.”

Just to be sure that the Eye was definitely 100% distracted, many amulets (like the Roman horse trappings below) feature both phalluses and rude hand gestures.

Diversionary tactics are not the only reason phalluses were thought to be effective combatants of the Evil Eye. They are also rather pokey, and everyone knows that pokey things are the mortal enemy of eyeballs. Many of you will be familiar with the Italian horn or corno good luck charm, which is an equally ancient manifestation of the same principle. As a wise friend recently pointed out to me, erections are basically human horns, so it makes sense that the corno could be used for the same purpose as a phallic symbol. Today, cornos have become the pointy amulet of choice, as penis-shaped jewelry is no longer considered the norm (bachelorette parties being the exception).

You can buy them at a million places on the internet:

A lot of them look like sperms.

For Romans hoping to take their amulets to the next level of protection, all of the aforementioned charms could be made out of a material considered apotropaic even before being carved as a magical member. Red coral is perhaps the most potent of these materials, as classical mythology intimately links the birth of coral to the death of the Evil Eye.

As Ovid tells it, coral was created when Perseus beheaded Medusa. The famous snake-haired Gorgon had the power to turn a person to stone with her gaze, and can be interpreted as a physical manifestation of the Evil Eye. On one of his adventures, Perseus placed Medusa’s severed head on a bed of seaweed. Blood dripped from her wound, petrifying the plants and turning them red. Nymphs took the stoney seaweed and scattered it throughout the ocean, creating coral. Thus coral was associated with Medusa’s downfall, and and to this day is worn to bring luck and protect from evil influences.

The pendant below is a nice example of how coral power can be combined with penis power:

Christie’s described the piece as being “naturalistically modeled…the pubic hair rendered in three rows of separately applied tight, snail-like curls.” It is really tiny, only 7/8” long, so I wouldn’t be surprised if it was once strung on a necklace with multiple tiny coral penis brethren.

Though the Evil Eye was regarded by many a real and serious threat, the absurd qualities of these artifacts were very much appreciated by their ancient users. Laughter itself was considered an effective weapon in the struggle against anger, envy, and depression, and an element of humor would have added another layer of protective magic to these amusing amulets. The common expression from our time, laughter is the best medicine, of course adheres to the same sentiment.

Perhaps the best message to take away from all of this is that a good dick joke can dilute even the most potent of evil forces. Also, if you type “phallus” into the online collections search of The British Museum, 1,022 objects come up.

Anna Rasche tracks down antique jewels for Gray & Davis by day, and helps run The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies by night. She is also a curatorial fellow at the Cooper Hewitt Museum, where she writes about old wallpaper for their Object of the Day blog.

Image credits:

1. Copper amulet in the form of a winged phallus. 19th century copy of a larger Roman amulet. British museum 2003,0331.26.

2. Bronze Phallic Amulet, Roman, 1st Century A.D., Metropolitan Museum of Art 60.117.2. Gift of A. Hyatt Mayor.

3. Bronze Phallic Pendant, Mediterranean, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology 50–1–40. Gift of Mrs. R. Hare Davis.

4. Phallic Agate Intaglio, European, British Museum M.582.

5. Child’s Gold Ring, Roman, 100–200 A.D. Victoria & Albert Museum 465–1871.

6. and 7. Bronze tintinabulum in the form of a winged phallus with legs; British Museum, 1865, 1118.208. Donated by Dr. George Witt. And Bronze tintinabulum with small bells. Roman, 1st century A.D. British Museum, 1856,1226.1086. Bequeathed by Sir William Temple.

8. Mano Fico, or “figa fist” charm. Illustration from pg. 153 of The Evil Eye: An Account of the Ancient & Widespread Superstition by F.T. Elworthy.

9. Bronze Horse-trappings in the form of a phallus, Roman. British Museum.

10. Google image search.

11. Graeco-Roman Gold & Coral Phallic Pendant, 3rd — 1st Century BCE. Sold for $5,569 at Christie’s London Antiquites sale 5488 in 2010.

11. Bronze Titinnabulum, Roman, 1st Century AD. Museo Arqueologico de Barcelona. Image via Flickr.