Since Living Alone

by Durga Chew-Bose

1.

I learned last summer that if you place a banana and an unripe avocado inside a paper bag, the avocado would — as if spooned to sleep by the crescent-laid banana — ripen overnight. By morning, that pallid shade of green would turn near-neon and velvety, and I, having done nothing but pair the two fruits, would experience a false sense of accomplishment similar to returning a library book or listening to a voicemail.

There is, it’s worth noting, a restorative innocence to waking up and discovering that something has changed overnight. Like winter’s first snowfall: that thin dusting that coats car rooftops and summer stuff like park swings and leftover patches of grass. Or, those two books that mysteriously fell off my shelf in the night, fainting to the floor with a cushioned thump! I place them back where they belong, pausing to stare at their bindings — of which I’ve committed to memory — if for no other reason than when you live alone, the droop of plant leaves, a black sock pocking out of my blue dresser, or an avocado that ripened overnight, all this stuff provides a rare, brief harmony: the consolidation of my things, all mine, in a space befit for staring off as I skirmish with a sentence on my screen or wait for water to boil. The only person who might interrupt my thoughts is me. Me, a word contingent on my mood, sometimes posed as a question, sometimes said with the inflection of a child pleading, Gimme! Gimme! Sometimes said as bait so as to needle myself away from cowardice and towards an unrealized Me. And since living alone, more so than ever before, claimed as a sturdy affirmation. Me.

2.

“When you travel,” writes Elizabeth Hardwick in Sleepless Nights, “your first discovery is that you do not exist.” This sentence, which I read in late September as I shuffled and flopped from my couch to my bed and then back to my couch again, chasing patches of shade as the sun cast a geometry of honey-dipped shadows on my walls, this sentence surfaced on the page like a secret I’d been hurtling towards all summer but, until now, was nothing more than a half-formed figment. (I’ve come to hope for these patterns that build in increments, eventually sweetening into an idea I’ve long been blueprinting in my mind; I’ve come to understand them as a huge chunk of what writing involves.)

So, while reading Hardwick, I noted that since moving into my one-bedroom apartment in late April I had travelled little, declining invitations upstate or weekends in Long Island or Pennsylvania. I chose instead to stay put. To seek the opposite of not existing and acclimatize myself, it turns out, to myself. Even writing those words now feels like a radical act, if for no other reason than a large part of who I am has always hinged on someone else — a daughter, a daughter of divorce (but with my own stubborn and cautious interpretation of what that means,) a child that never quite reveled in the traditions of childhood, a younger sister (and her eventuate appetite for the sentimental, for the Beastie Boys, for video game posture, for asking “What did you eat for lunch?” when what I meant to say was, “I love you.”).

I was also someone’s girlfriend and subsequently, the emotional commerce of being someone’s ex-girlfriend, or the person whom you write emails to at 2 in the morning, or the person whom you are expected to dislike, or the person who finds herself stuck between a plant and a kissing couple at a stranger’s party.

I was a roommate to three people and a cat, a roommate to one person and two cats, a roommate to someone turned sister, forever.

I was the loyal friend but also, the girl who never answers her phone but who will text back immediately: sorry. everything ok?

I was the witness at your wedding, who took a tequila shot with you before City Hall in a bar full of mid-afternoon men with bellies — they all swiveled right in unison as we walked out, you in silver-plate heels and me in overalls.

I was the woman whose shoulders are too bony to lean on but whose thighs have cushioned his naps in that hour on Sunday before dinner when the hangover has worn off and the sleepy sets in.

All of these relationships, crucial as they were and are, accelerate involuntarily. Being Someone’s Someone is cozy in theory — a snug image like two letter S’s fitting where the convex meets its concave. Unfortunately, I felt little of that snugness. I’d sculpted myself into what feels nearest to apparatus, a piece of equipment that was increasingly capable of delaying my desires. Of slow-drip longing. There was always tomorrow, I told myself. There was always next semester, or spring or the uncanny extent of a summer day. Or winter. Or winter, she says. The most fictional of seasons because winter is lit for the most part with lamps and candles and in some cases, the arbitrary oranges of a fireplace, instead of the natural brightness say, of the sun. Winter’s wheaty indoor amber glow emboldens the bluesiest approach to oneself, which is by nature the easiest to deny. But repudiating the would-be is a quality that many women can attest to no matter the season, because from a very young age we were never young.

I can wiggle my way into small spaces. I’m more flexible than I appear. I sleep in the fetal position and I can hold my breath while smiling and for longer than is considered safe. I do everything in my power to stifle a second sneeze and if that fails, I apologize mid-sneeze. Atchoo-scuse me! Because I have a low pain threshold, I seem to have developed, as a reaction, a high tolerance for the swell and plummet of other people’s moods. And so I whittled myself away because — and this is where as a writer I duck and cover — I’ve been for most of my life confusing the meaning of words. I’ve confused privacy with keeping secrets, for example, and caring with giving. For years, the words none of your business boomed like an affront, a provocation I could never affiliate with let alone use. But now I have a better understanding of what they stand for: mine to share if I so choose. Those words dangle with a sense of pride and gut-vanity like a bracelet I just beaded and am holding up admiringly. Look! Isn’t it pretty?

3.

In the past my response to conflict was, by some means, bogus math. Prescriptive as though the advent of apology was, I was convinced, my first move. Figuring myself into the equation would come second because I had disciplined my definition of ‘relationship’ into rationale. Ensure he feels proud of his work before you can focus on yours. Read little into what she said last night; she’s having a hard time. Listen. Listen better. Master listening.

But living alone is the reverse of mastery. It’s scuttling around in surrender while hoping you don’t stub your toe because living alone is also a series of indignities like bouncing around on one foot, writhing in pain. Living alone is an elaborately clumsy wisening up.

I can’t be certain, but since moving into this apartment on the fourth floor of a building just one street over from my previous place, I regularly trip over things: shoes, computer cables, the leg of a chair, and of course, ghost things, too. Just yesterday I placed a clean pot back on the top shelf of my kitchen cabinet only to have it slide back out and conk me on the head with such aggression that when I yelled FUCK, everything went silent: my buzzing fridge, the patter of rain on my air conditioning unit, the slow and sped up metronomic tic that resides inside of me that forebodes and competes with my heartbeat for what really compels me. Any vain attempt to expect jokiness, for instance, from a pot that mysteriously falls on my head, no longer exists. Since living alone, grievances occur in silence. Deep and shallow thoughts court and compose me like deep and shallow breaths.

4.

As someone whose central momentum is having connected (similar to the high of having written), my life before living alone was, to exaggerate, one very long practice session. I’d been avoiding myself with such ease that even when an obstacle presented itself — like the pained limits of a friendship that had run its course — my response was to adapt around it the way we circle street construction on our way to the subway without much thought, as if the ball and sockets of our hip joints, anticipating those orange pylons, swerve so as to save our distracted selves from falling into crater-sized holes.

Avoidance can be elegant, certainly, because elegance (like restraint) is a spectacle that assuages. Even the word — assuages — smooth as if meant solely for cursive’s sleek lines; a speedy unthinking gesture like one’s signature.

Edmund White once wrote about Marguerite Duras in the New York Review of Books: “…her work was fueled by her obsessive interest in her own story and her knack for improving on the facts with every new version of the same event.” In less than 30 words, a tally of 4 her’s.

I count living alone as, in a manner of speaking, finding interest in my own story, of prospering, of protest, of creating a space where I repeat the same actions every day, whetting them, rearranging them, starting from scratch but with variables I can control or conversely, eagerly appeal to their chaos. I can approximate what time it is on sunny mornings by glancing at the frontiered shadow that darkens on the building adjacent to mine, casting a crisp line that cuts the building’s sandy-yellow brick, lowering notch by notch as quarter past six all of sudden becomes seven. It takes me fourteen steps from my bed to my bookshelves and nine steps to walk from my front door to the globe lamp I’ve propped on a stool under a wall I’ve half-decorated, of which a poster I’ve framed hangs asymmetrically next to nothing more than blank white wall. That globe lamp is the first light I turn on when I return home. For nine steps when I walk in at night, after shutting my front door and placing my keys on their hook, I navigate the slumbered mauve and moon-lit darkness of my space. It welcomes me; the darkness and I suppose the lamp too.

5.

Living alone, I’ve described to friends, is akin to waking up on a Saturday and realizing it’s Saturday. That flighty jolt. That made-up sense of repartee with time. Abundance felt from sitting upright in bed; the weight of one’s duvet vanquishing, by some means, all accountability. Rarely travelling for half of last year and staying put in my new place all to my own was akin to the emotional clarity yielded from those first few sips of red wine, or from riding the subway after a seeing a movie; riding it the length of the city only to forget that this train dips above ground as it crosses the East River, suddenly washing my face with sunlight or in the evening, apprising my reflection in the train’s window with the tinsel of Manhattan’s skyline.

Precision of self was a quality I once strived for, but since living alone, clarity I’ve learned — when it comes — furnishes me with that thing we call boldness. The way readjusting my posture as I write accords me a new lease on the day or newfound impertinence towards punctuation. Self-imposed solitude developed in me, as White wrote about Duras, a knack for improving on the facts with every new version of the same event. And living alone, I soon caught on, is a form of self-portraiture, of retracing the same lines over and over — of becoming.

There’s just one problem. Nothing catches me off guard quite like suddenly — sometimes madly — seeking the company of someone else.

In those moments, the whiplash of loneliness can impose temporary amnesia. How did I end up here? Had I lectured myself into some smug and quarantined state of solitude? Was living alone analogous to the emotional moat I construct around myself whenever I listen to one song on repeat, again and again? No, not exactly.

Becoming is precarious terrain and in spending so much time on my own, I had perhaps developed in solitude an acute distrust of myself. Seeking, I’ve since learned, is okay. How many women, I wonder, caught off guard by an unexpected stream of tears, have walked to their bathrooms and glanced at their faces in the mirror? A brief audit: dewy eyes, flush cheeks, damp and darkened bottom lashes that cling like starfish legs, but mostly, the way my face, shook by what is happening, to the daze of unforeseen peril, finds solace in all the inexplicables that on some days come at me with suggestive force. I am a daughter, I remember, with parents whom I can call. I was once someone’s girlfriend for those formative girlhood-spun-sovereign years, so that’s surely something I’ve carried. What else?

I tend to forget or rather, rarely cash in on — like coupons piling up — the proximity of people. If I wanted, I could walk a few blocks and find a friend, a friend who is likely experiencing coincidental gloom, blahs, and Sunday doom, because if there’s one thing I know to be true about New York friendships: they are intervened time and again by emotional kismet. Stupid, unprecedented quantities of it. We’re all just here, bungling this imitation of life, finding new ways of becoming old friends.

6.

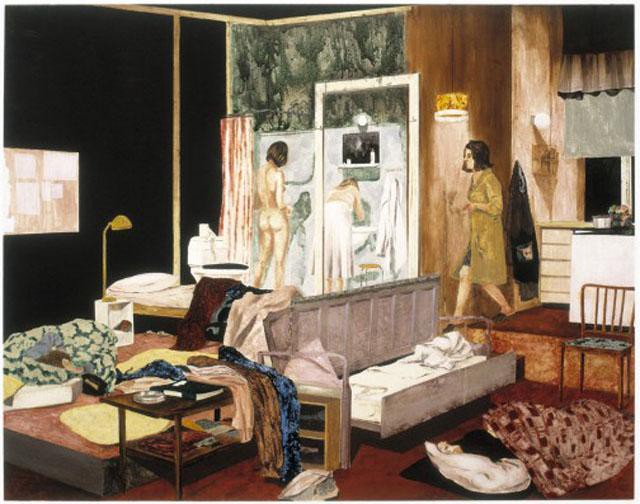

There’s a painting by one of my favorite artists, Swedish painter Karin Mamma Andersson, titled Leftovers. In it, a woman is depicted living in her apartment, occupying the space in five separate moments of time. Sleeping. Dressing or showering, it’s hard to tell. Sleeping once more. Washing her face. Going out. The space has the meticulously worn character of a stage; set designed attributes like a lone chair, blouses flopped on a coffee table, and the miniature dollhouse-like synthesis of square footage. In this way, Leftovers reminds me of my apartment. A collection of stuff, all hers.

Parsing Andersson’s painting was for one summer, a pastime of mine because I had chosen it as my laptop wallpaper. Staring intently at this anonymous women’s space, her camel coat and mustard floor lamp, her bathroom sink — too low as most bathroom sinks are — I began to endow her anonymity with qualities of my own. These are the games we play as women because since birth, interior spaces have been sacred; have been where we imagine furniture mounted on ceilings or marvel at the weight of curtains and fabricate for fun what lies behind them — where we trace patterns in the lightening and darkening of a velvet couch as we eavesdrop on adult tensions.

Perhaps she too, leans against her sink in the morning as she sips coffee, worrying without right about everything, or cruelly and quite shamefully envisioning the funeral of someone she loves. Perhaps in living alone, she like me, experiences self-voyeurism, self-narration, self-spectatorship more sharply than ever before. Doing domestic things like the dishes or dumb young things like ordering takeout while perhaps still drunk the next morning. Both versions of me, since living alone, have settled into a one woman show that I star in and attend, that I produce and buy a ticket, but sometimes fail to show up to, because as it happens, living alone has only further indulged the woman — me — who cancels a plan to stay in and excitedly ad-lib doing nothing at all.

And yet, I’ll still attempt pursuing these delusions in spite of reality’s firm hand, in spite that which keeps us indoors: money, panic, books that lay in piles near my Nikes, books I absentmindedly begin reading instead of tying my laces and walking out the door.

7.

The first thing I ate in 2015 was a pear my friend Katherine left at mine on Christmas Eve. The pear, brown and stout as if missing its neck, was a pear unused, spared from a dessert she had prepared for dinner that night. Something with cinnamon and whiskey and perhaps another ingredient, I can’t be certain. Lemon juice? Before leaving, she placed the brave little stray on a shelf in my fridge. It sat there for seven days and eight nights, wrapped in a plastic bag that clung to its coarse skin as if suffocating it. Pears, I thought whenever I’d open my fridge during those haphazard and floppy days that wane between Christmas and New Year’s, pears should never be wrapped in plastic. Paper, I concluded, is what suits.

It’s likely this notion has something to do with The Godfather, the second one, because one of my favorite scenes in the trilogy occurs moments after Vito Corleone has unfairly lost his job, yet still returns home to Carmela carrying a pear wrapped in newspaper. He gently places the gift on their table while she busies herself in the kitchen and in those few seconds I’ve always been taken by what I can only describe as the privacy of kindness. Those moments leading up to — that anticipate — the testimony of kindness. Kindness before it has been felt, before it, by nature of its mutual construction, even exists. Kindness at its clearest.

On New Year’s morning, I woke up and placed a cutting board on my stovetop and sliced Katherine’s pear in four fat slices that I then halved so as to begin the year with a sense of plenty. I stood at my counter and ate each piece as if I had intended to do so all along, as if I had waited all of 2014 to eat that pear.

That’s the thing about living alone. Artificial intention blurs with real intention, and sooner or later, more choices than not — like eating a pear first thing in the New Year — seem decisive, so much so, that even a pear can deliver purpose and if you’re lucky, peace of mind too.

Durga Chew-Bose is a writer living in Brooklyn.

Image: The Leftovers by Mamma Andersson, 2006.