Freeing the Inner Wilderness: A Conversation with Filmmaker Josephine Decker

by Katy Kelleher

Certain stories get told over and over again for a reason. Usually, the stories that survive for centuries dance around (or wallow in) our base themes: lust, violence, greed, vengeance. These ugly things are the stones that build our fairytales, the foundation for our myths. From different mouths and different lips come the same timeless stories, repeated, recited, and regurgitated, over and over, and we never tire of it. At least, I don’t.

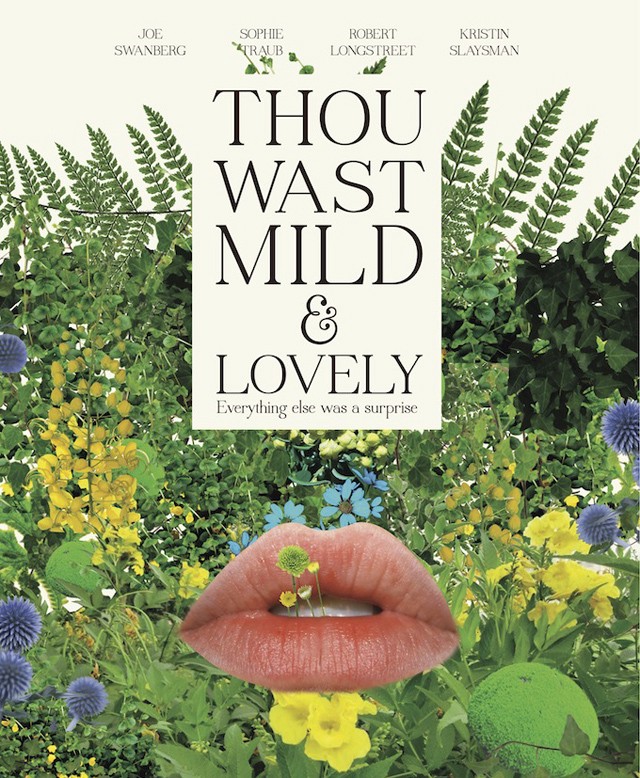

I’ve loved folk and fairytales all my life. I like them modern, I like them old, I like them sung, read, spoken, and shown. In Josephine Decker’s film Thou Wast Mild and Lovely, she does all four. In this strange and electrifying movie, she pulled me slowly under, drowning in the story of this rural family American family and their bucolic-yet-impoverished life. It’s a story about women and their lust, men and their greed. Butter on the Latch, Decker’s other first feature film is similar in style, yet different. This one follows one woman from Brooklyn to a Balkan folk camp, where she goes to sing old songs with an old friend. It’s about the loves that happen between women, the ways that we betray and hurt each other. It’s a folk song for a modern age.

Josephine released these two films at the same time, and people have noticed. It’s not every day the New Yorker heralds a young female talent as their next big thing, but that’s honestly not why you should watch these movies. You should watch them because they’re experimental and strange and sexy. Josephine and I spoke about American folk tales, redefining the word “masturbatory,” and blending fantasy with reality.

Were the movies designed to speak to each other? They say really similar things about the weirdest elements of our behavior. Did you plan for them to be companion pieces?

Originally, the concepts for the two films were that it would be one feature film, and half would be Butter on the Latch, half would be Thou Wast Mild and Lovely. I knew I wanted to create a movie about the Balkan folk camp, and I love American folk tales. Then Butter on the Latch turned out to be much longer than I thought, and as I began to work on Thou Wast Mild and Lovely I became more and more invested in that story. What started as two shorter pieces — one about the Balkan music camp, and one inspired by American folk songs — turned into two different movies.

I love folk music of all kinds — and folk stories and folk art. And both these movies definitely call on those traditions, but it’s like you pull them apart in these new and strange ways. I guess that’s not a question. Okay, so, here’s a question: What does “folk” mean to you?

I grew up with folk tales. I was a child of the ’80s and Masterpiece Theater was huge. It was the height of Disney and The Little Mermaid and all those movies, but I was also reading the original stories and reveling in how dark they are. I have always been into folk tales and fairy tales. I started playing piano when I was seven and that’s a big, important part of my life. For a long time, I felt like I could say things with music that I didn’t know how to express with words. And folk music is essentially storytelling with music. And that’s what I want to do with my movies: to tell movies in an energetic and tone-oriented way instead of just plopping plot, plot, plot.

There’s also something really important about community. These old stories are all so deeply related to the communities that they came from. I’m obsessed with the idea of community. I can’t make a relationship work to save my life, but I love being part of communities. I think folk songs draw deeply on a real relationship, not just with a spouse or a lover, but in the context of this shared experience.

I don’t know if I answered the question at all, what does folk mean? I think I can answer that in only a really personal way.

That makes sense — that was kind of a rough question! But when I watch your movies I feel the sense that it’s a folk tale, it has all the elements, including animals that feel human, animals that become part of the community. In Thou Wast Mild and Lovely you had a scene that was shot from a cow’s point of view. It’s funny and strange and definitely a new way of storytelling, but it also feels almost traditional at the same time.

I love animals. My goal with my next film is to have a lot of it be shot from the point of view of different animals. I keep banging my head against the wall of that movie though. Even while I keep saying, “This is going to be so great, it’s going to be so great!” I have trouble wrapping my head around how it will work.

When I think about every movie that I’ve made or that I think about making, it has animals as main characters. Even if they’re half-human, half-animal, they’re always a big part of the lives of the characters themselves. That’s so funny. I guess those Disney movies did work on me!

When I was little, I imagined that the woods would be this place where animals were just frolicking around like crazy and always happy to help you get dressed. And then you grow up. And you realize that will never happen, and that the woods are a place where either all the animals are dead, or all the animals are wild. That these places aren’t safe. It’s a weird realization.

You mean realizing that animals aren’t like you imagined?

Or just… the realization that the entire whole world is a lot less domesticated, a lot more feral, than you thought it was.

Yes! You know, that’s a good way to describe what my movie is about. And I think that’s also what our inner worlds are like. I grew up in Texas, and it was so rigid in ways that now feel ridiculous. As a kid, I felt like you had to approach religion in a certain way, and that you had to approach and understand sexuality in a certain way. But the truth is that we’re all wild animals. Whether we want to or not, we act, and maybe we should act, out of instinct. I think when we tamp that down, when we try not to be creatures of instinct, we feel sad. These films are about that — what is that inner wilderness? What are our points of access to that? How can we free that place?

Reality is really ambiguous and porous in both Butter and Mild and Lovely. Was that intentional?

Definitely. I was going to say that’s what life is like. Is that what life is like? It might be for me. I think there is so much miscommunication in life. So often we make these assumptions about ourselves and other people. Too often we’re seeing the world through a lens of our fears. Blending fantasy and reality feels very natural to me. I think that’s also how I cope with reality. Ever since I was a kid, my space to play and be safe was in fantasy worlds. The real world is chaotic, but I could understand a fantasy world better. In the fantasy world, people will try to kill you, and monsters eat you, and mothers eat their daughters. That feels closer to my experience than the “reality” we live in where everyone is supposedly on each other’s side. Sometimes, I think extremes can be more realistic than realism.

You swing really quickly in your movies between those two things — banal everyday moments and shocking extremes. You also swing between erotic and violent so fast. And I don’t mean this aggressively, but what are you trying to say about sex here?

I’m not trying to say anything, which is actually a really important point. I’m trying to access something that feels really true and real for me. And for violence paired with sexuality — ironically, I had a really good conversation with a sixteen-year-old when I was scouting in Canada. I went to this woman’s house, who was in her seventies, and she was located out in the middle of nowhere, three hours south of Calgary right in the mountains. She had this beautiful home that was built by their family, and she was very close to her granddaughter. So I sat down with this 70-year-old woman and this 16-year-old girl, and me, in my thirties. We sat down and talked about the film, and we ended up talking about literature. This 16-year-old said to me that she really likes violence in movies, but doesn’t like it in literature. I asked her why, and she said: “I think it tells more about a character in a small amount of time in a movie. It can say more than most other actions.”

That’s a smart kid.

And she’s just 16! Yeah, it does feel true. That’s not my reasoning, exactly, but subconsciously I’m trying to share something quickly and efficiently. I’m trying to share something that feels real to me on a deeper level, and my experience of sexuality is that there’s a heightened pleasure when there is a potential for punishment. That’s what making out in your parents’ living room is all about. I take that to an extreme. The fear of getting caught makes the ecstasy that much more interesting.

Maybe the flip side of the fear of being caught is the sense of pleasure that comes from being watched. In Mild and Lovely, Sarah seems like she loves to be watched.

I think I’m kind of a voyeur. I was actually really shy as a child. I’m pretty talkative now, but I’m making up for sixteen years of being completely terrified to say anything. I spent so much of my life watching rather than participating, and seeing the way that other women were sexy and sensual, and the way that they could move through the world with grace and ease and even take pleasure in their mistakes. That was something I felt I had no access to. I remember being a middle-schooler bumping into everything, and I felt in awe of certain women. I think this is a thing that all girls have. I don’t know what the exact definition of girl crush is, but I had this girl fascination. I wondered, “How does she do that? How does she so effortlessly manage her identity around these ten-year-old boys and her friends and her teachers? And how do I have none of that?” I think a lot of my movies are about seeing and witnessing, and not necessarily being a part of the thing that is happening.

When you describe that girl, I immediately picture that girl for me. That girl that I would watch and she knew she was being watched, and I remember feeling so envious. Maybe that’s why we do things like make movies or write.

It’s really funny — I want to raise my kids to be more balanced than I am. I want them to feel loved, and to be really emotionally intelligent, but then they won’t be artists! It’s really that I just spent so much of my life feeling like I couldn’t say something that I desperately needed to say. I think that’s what drives a lot of people to make art. I couldn’t be honest or express myself in any other way than playing the piano. Now I’m intimate with myself — and the world — though movies. Maybe intimate relationships will come next!

That reminds me of how people often call movies “masturbatory projects” as an insult, but maybe that’s a really lovely thing to be. There’s a fundamental value in being intimate with yourself.

That’s true! But you would have to redefine what masturbatory means. The movies that feel most masturbatory for me are the ones that are overly concerned with giving the audience what they want or seeing things in a certain, predetermined way. But masturbation is the opposite of that. It’s about recognizing all of the flaws of your own body and recognizing what turns you on and being vulnerable. It’s loving.

Do you consider yourself a feminist filmmaker?

I’ve never thought about being a feminist filmmaker, but I definitely identify as a feminist. I’m part of the Film Fatales [a collective of female filmmakers in New York], and one of the recent conversations we had was about whether we have a responsibility to make hopeful films in these kind of dark times. Of course, I reacted very much against the question, but a lot of the women in the room did feel that they had a responsibility. I think the other question is: What responsibility do you have towards women as a female filmmaker? I would say in an ideal world, none. That’s the best kind of feminism. Where you can be responsible to yourself, be a filmmaker creating films that excite you. That’s my brand of feminism. Women should make films about whatever the fuck they want to make films about. But I was definitely raised a feminist — my mom was an activist. I’m not afraid of that word at all.

But you know, someday, I think we’re going to work in a world where more of film and television and media is run by women and not by men. There are these amazing female stories that have a potential to land in a huge way with a female audience, and I think too many men either don’t like them, or don’t get them. It’s so exciting to be making art in a time where it feels like that can change.

Were you raised in a religious environment?

I still call myself Christian, but my community — I moved to Dallas when I was ten — but the community around me was very conservative. I think one of the biggest reasons I still call myself religious now is because one of the most liberal and open groups around me when I was growing up was my church youth group. That was where all the weirdos who were slightly suicidal and depressed hung out.

You have a background as a performance artist — how has that influenced the work that you do?

I have an activist side, but I don’t want to make message movies. Some of my performances are about environmental issues. But I think the biggest difference is that there is such a huge level of vulnerability in performance art. It has helped me create characters that are more fearless, and to work in a fearless way. Being able to expose yourself, not just nudity but emotionally to the world, and then when the world embraces or supports, or even just witnesses silently — I think that’s important.

Another thing that I love about performance art is that it’s all about being present. Being totally present to myself and my body and the world. And that’s the opposite of filmmaking. Every second you are holding the entire movie in your head, wondering if each scene feels consistent with the last one, if the sun is going to set and ruin the shot. When you’re acting or performing, your job is to stay in the moment. It’s a kind of freedom.

Image by Zefrey Throwell.

Katy Kelleher is a writer living in Portland, Maine. She is currently collecting ghost stories. Do you have a ghost story? Email her: [email protected].