Angela’s Ashes

by Sarah Liss

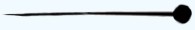

In the early autumn of 1994, fuelled by a kind of defanged hubris, my friends and I dyed our hair Angela Chase red. To be fair, the particular shade was probably called something like Bordeaux Whimsy or Garnet To Hell. But when, moments into the pilot episode of My So-Called Life, Claire Danes’s 15-year-old Angela Chase looked up from the sink — bewildered and brazen with rivulets of Crimson Glow running down her neck — we found our lodestar.

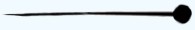

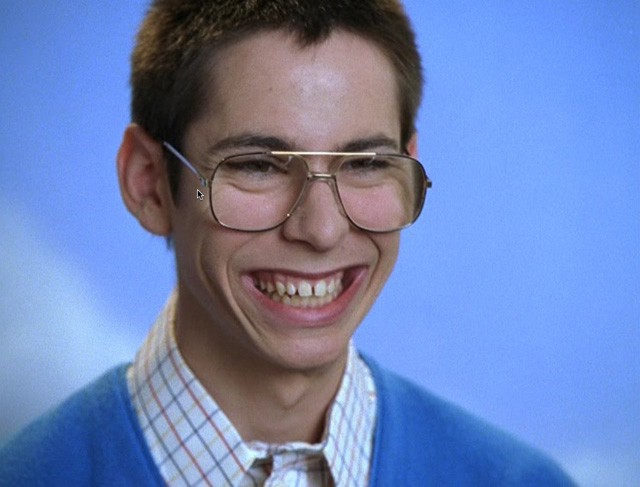

Over the next 18 episodes, we lived My So-Called Life by proxy, parsing every lingering exchange, every painfully awkward faux-pas, every elbow-bruising, shearling-swaddled boiler-room makeout session between Angela and Jordan Catalano (to this day, the single greatest contribution Jared Leto has made to humankind — pace 30 Seconds to Mars fans), with manic zeal. Today, I can still recite from memory lines like: “People are always saying you should be yourself, like ‘yourself’ is this definite thing, like a toaster.” Whatever, roll your eyes — during our days of Bordeaux Whimsy, these were our koans.

So when the show was unceremoniously cancelled a mere five months into its so-called life, we were understandably devastated. We were swept up in the tide of the MSCL web community, reportedly the first such online movement. In the end, it wasn’t enough: They killed our psychic proxy. No Chase-ian koans could help us come to terms with this grievous wrong.

This month marks the 20th anniversary of that cruelest cut: On January 25, it will be two whole decades since My So-Called Life went dark, leaving a vibrating nexus of possibility and plot points in its wake. All these years later, even now that I have a kid, now that I have a job, now that I’m — ugh — basically the same age as Patty and Graham, the lovable but maddening Chase parents, Angela and Rayanne and Sharon and Ricki and Brian and Jordan hold an exquisitely dear place in my heart. What I find strange, though — what I never could have explained to myself back when I was a 13-year-old Gordian knot of anxiety and Crimson Glow-stained earlobes — is this: my love for these characters and their stories endures because of their short-lived tenure on the air, not in spite of it.

Imagine if you had the power to determine whether a well-known public figure — beloved by some, despised by others, the source of great ambivalence to many — should be put to death. For the sake of argument, let’s say that this hapless individual was a cherished confidante: someone whose borderline-tasteless jokes had elicited gales of laughter, whose personal tragedies had inspired your own fits of ugly-crying, whose company had reassured you while eating congealed day-old takeout. And what if this dead man walking was in such a position through no fault of his own, if his fate was simply the result of a combination of tragic circumstances and the whims of a callous bureaucracy? Would you not rise up, fists raised, and fight for the poor sod’s survival?

Of course you would. A man’s life hangs in the balance!

This is the reasoning, I reckon, that fuels the feverish, breathless crusades that spring up, season after season, to preserve programs on the verge of cancellation. These days, there’s nothing a TV fan fights harder for than to keep his show alive. You can barely hear the laugh track above the din of all the rallying cries: “Save our Bluths!” “Save Greendale!” “Save Cougar Town!” A man’s life hangs in the balance! Trophy Wife, a recent passenger on the television equivalent of the Titanic, inspired impassioned campaigns, petitions, and listicles from critics and viewers alike, but all “22 Reasons to Watch, Love, and Save ABC’s Trophy Wife” couldn’t steer it away from that iceberg marked SAYONARA.

Even if you don’t feel the same way about the targets of their efforts, you can understand why these devotees pool their resources and broadband to save what they love. After all, they’ve seen it work in the past: Community, for example, has risen from the near-dead so many times it might as well be a plotline in a George A. Romero zombie movie, its current incarnation haunting us from the purgatory of Yahoo. And just last week, Netflix chief content officer Ted Sarandos broke the perplexing news that Arrested Development would stagger back for a fifth go-round — even though its wildly anticipated fourth season, which came out in 2013, seven years after the show was cancelled, landed solidly in the “Meh” category.

Bob Dylan once sang (on his worst album of all): “death is not the end.” This seems to be the prevailing belief when it comes to cherished series that have gotten the axe. But perhaps we’ve gotten it wrong. Put down your placards, brethren and sistren; hold off on those indignant blog posts. What if death isn’t just the end, but, in fact, the best possible outcome for your beloved TV friends?

Obviously, I’m not unsympathetic to the plight of the bereft fan. I’ve experienced that irrational passion. I’ve been consumed by a frantic, overwhelming desire to convince the powers that be to save our show! using whatever means necessary. Most recently, like so many others, I yearned to pull out the jaws of life for Bunheads (RIP), Amy Sherman Palladino’s weird and warmhearted dramedy about a scrappy, neurotic Vegas showgirl-turned-small-town-dance instructor — finally, a panacea to fill the Gilmore Girls shaped hole in my heart! — which was given the axe by ABC Family in fall 2013.

And yet, even as I wept for the rapidfire banter never to be spoken, as I mourned the elaborate choreographed sequences that would go un-danced, there was a tiny, wistful part of my subconscious that wondered if this premature departure was for the best. (It was too good for this world! It is in a better place now!)

Because [SPOILER]: television shows aren’t actually people. We just experience them that way, because — like people — episodic series are things with which we have intense ongoing connections. Our emotional responses to these shows reflect our psychological state while we’re engaging with them; we project our real-world feelings onto the characters in these fictional universes (and the actors who play them).

For example: Valerie Bertinelli and I, we’ll always have Paris.

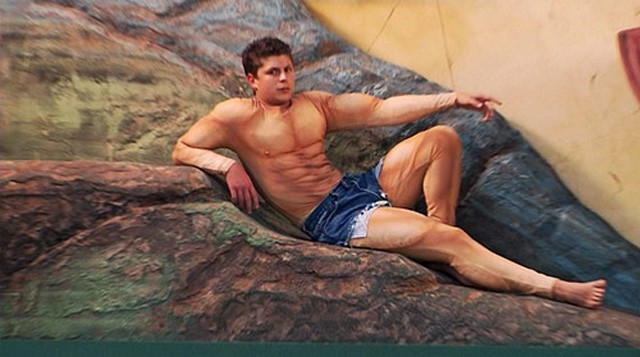

That’s where we met, back in 1993, when I was a nerdy 12-year-old Torontonian with little more to do on a Saturday night than practice my Bat Mitzvah portion, and she was a naïve but scrappy young American working as a waitress in a charming café in France. I watched her serve rude customers (adorably) and offend “Parisians” (adorably) with her atrocious pronunciations of French words, while I sat on the scratchy couch in our den and muttered half-baked Hebrew under my breath. Café Americain, which was shot on the Warner backlot and starred Bertinelli alongside bunch of other actors you’ve never heard of, ran for just one season on NBC before it disappeared, with no fanfare, into the fog.

This all means nothing to you, I’d wager. It’s unclear whether even Bertinelli recalls that brief, magical foray into broad European stereotypes (French people — they’re snooty and hilarious!). No one is arguing that Café Americain was killed before its time; some might claim that it overstayed its welcome. In my mind, though, this aggressively mediocre sitcom is crystallized as a touchstone that emits trippy 1993 vibrations whenever it skims the surface of my consciousness. Bertinelli’s Jenny Craig commercials gave me Torah-school flashbacks; when Maurice Godin (incidentally, a fellow Torontonian!) showed up in a handful of guest spots on House, I could feel the taste of Diet Crystal Pepsi rising in the back of my throat.

For me, this weird footnote in Bertinellian history stands as a sweet, incredibly vivid memory of tweendom, the pop-culture equivalent of a prepubescent crush. To return to my point above: television shows aren’t people (a man’s life hangs in the balance!). They’re more like relationships. And if you’ve ever tried, desperately, to keep a relationship alive despite all signs to the contrary, only to give up after it limps and dwindles to its pathetic death, then perhaps you can see why, more often than not, the best thing you can do for a show that you love is to just let go.

Granted, not all axed series are abysmal. For every Café Americain, there is a Bunheads; for every Dads, there is a Freaks and Geeks.

And above all, there is My So-Called Life. It may appear as though I’m comparing apples to crapples by holding up this canonical teen show alongside the dreck of Café Americain, but there’s something rare and special about shows that burn brightly for a single brief moment and then disappear. Surely you’ve had a brief affair that was cut cruelly short but has assumed a hallowed, near-holy glow in the dim candlelight of memory. If we approach these programs as beautiful, fleeting moments in time, we allow them to be perfect examples of themselves, to be seared into our goopy, synapse-laced grey matter, destined to forever trigger full-body flashbacks — and, if we’re lucky, connect us with kindred spirits.

Television has value as pure entertainment, and of course it can edify and awe and force us to challenge our own preconceived notions about drug kingpins. But if we’re to believe the brand of cultural criticism that has flourished in our current golden age of TV, it’s that the medium’s great strength, maybe even its truest purpose, lies in its ability to galvanize collective experience. Recognizing fellow acolytes is how we root out members of our tribe; making connections over obscure details or finicky plot points is how we forge alliances.

If television is the raw material from whence the spongy interstitial fabric of culture is made, then it follows that every esoteric deconstruction of a particular episode (or character, or trope) is the end product, a processed commodity that has the magical ability to make us feel simultaneously special and not alone.

Even more than what is, we’re fascinated by what once was, and what that means for us now. And the more obscure the experience, the more potent the sense of tribal identification. Curiously, this also means that in some ways, a series that leaves us too soon — especially one given the axe in its prime, with so many plot twists untwisted, so many Emmys unwon — has the best chance of a nostalgia-driven afterlife.

I’m not suggesting that My So-Called Life — or Bunheads, or Freaks and Geeks, or Trophy Wife — had achieved its full potential. Or, for that matter, that the best thing for a top-quality show is to hack it down when it’s on top. But I do think that we have a regrettable tendency, as a collective TV-watching public, to get awfully myopic about the programs that we love, to cling desperately to some idealized notion of them even after these series have long passed their prime.

I don’t know where shows go when they end. I’d like to imagine it’s a relatively pleasant kind of purgatory that falls somewhere between The Muppet Show and a Matt LeBlanc comeback vehicle. More and more, though, I’m starting to think that what happens after cancellation is less about a final resting place and more about a creepy liminal space that precedes resurrection. There are all the corpses — the withered, urine-stained trunk of Up All Night (2011–2012), the snarled, gooey entrails of Ben and Kate (2012–2013) — just waiting for some necromancer to work his or her magic.

At times, the call from the zombie overlord might come from inside the house, as it did in the case of The Killing, a drawn-out murder-mystery that infuriated its fans and was itself killed after its second 13-episode arc, then rose, gasping, from the grave for a third and final season before AMC lopped off its head for — oh, no, wait! It’s back again!

All of which is to say: Sometimes we just have to say goodbye, and hope — or know — it’s for the best. In Casablanca, close to the real fictional Café Americain, Bogey’s Rick forces Bergman’s Ilsa to get on that damn plane to Portugal. If she stays, he insists, she’ll only regret it. “Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon, and for the rest of [her] life.”

And now that my Crimson Glow flirtation is nearly 20 years behind me, I have a suspicion that My So-Called Life’s untimely end might’ve been the best possible resolution — for all parties involved. When pop-culture artifacts resonate so perfectly at a particular moment in time, they tend to look less and less appealing the longer they stick around. And when you love a thing so deeply and fiercely, that thing has the potential to let you down in a way that’s just as deep and fierce, and that potential only increases over time. If it dies, it can stay frozen in time, a mutant mosquito in the giant shard of Jurassic Park amber that is our collective consciousness.

Angela Chase never had a boring relationship or became a cheerleader to satisfy some hackneyed narrative leap, or said things that, hel-lo, she totally wouldn’t say. There she is, forever 15, uttering aphorisms that sound like adolescent Rilke. And here I am, two decades later, still parsing them with absurd teenage adulation. Way back when, I wanted so badly to save Angela from network annihilation — a girl’s life hangs in the balance! These days, I’m glad that I failed in my mission.

Sarah Liss is a writer and editor who lives in Toronto. Send her Gilmore Girls GIFs @lisstless.