Welcome To My World: El Máximo, Exótico

by CaitlinDonohue

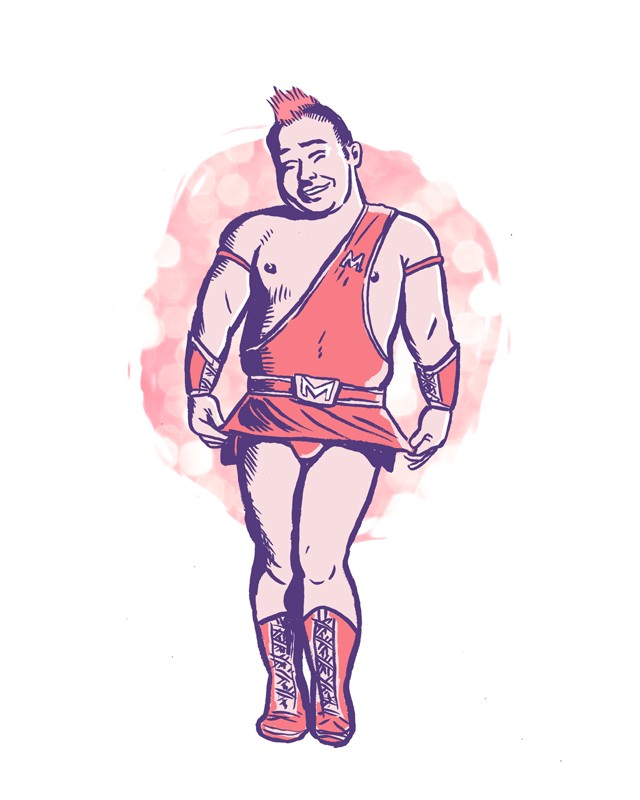

I don’t remember buying “section gay” tickets for our first Mexico City lucha libre event. But there we were, myself and a small pack of fabulous queerdo friends from San Francisco, thrilling to our first trip in one of the world’s largest, coolest cities — a place that would soon become my home, though I didn’t know it at the time. Delighted by the anti-hetero raucous taking place around us, we set our massive paper cups of light beer on the floor to join the crowd in a rhythmic scream-chant. “BESO, BESO, BESO,” we squawked, signaling our collective desire as an audience for the pink Mohawked wrestler in the ring to finish off his opponent with a smooch. Eventually he obliged to a deafening cheer and many exclamations of joy from our row. Competition vanquished, he flounced down the runway that led from the ring, the TV-optimized lighting glinting off his pink, and shiny mini-toga.

Lucha libre is known for its campy antics. The much-beloved Mexican wrestling style features sweaty, grappling men and women in Lycra masks, lace-up boots, and tights that leave little to the imagination — and that’s the sport at its most hetero. For decades — since the 1940s, less than a decade after the first professional league for the sport was formed in 1933 — lucha has had a queer streak running through it. This vein of flamboyance is known as the exóticos, lucha libre’s gay-playing wrestlers who may or may not identify as LGBT outside the ring. The exóticos are typically rudos, luchadores who play bad guys. They’re conniving in their flouncing and have no qualms in using their character’s sexuality to score one on the bros. An exótico may psych out an opponent by propositioning them in the ring, or distract them by a particularly well-turned hand flourish executed before landing a blow.

The proud, prancing tradition is believed to originated with Dizzy “Gardenia” Davis, an American who competed in Mexico and tossed his namesake flowers to the crowd at matches. It is said that George Raymond Wagner, otherwise known as famed American wrestler Gorgeous George, modeled his own dandified persona on the antics of Davis and luchador Lalo el Exótico — -Wagner used to bring a manservant to the ring, tasked with disinfecting fouled surfaces and to spread rose petals at Wagner’s feet.

Until the 1980s, the exóticos said they were straight outside the ring. It was then that gay-for-pay wrestler Rudy Reynosa — -reportedly the first to employ the knockout kiss move — -started mentoring a couple of out bar employees. Once they were ready to fight, they became May Flowers and Pimpernela Escarlata and officially joined Reynosa to become a bad-ass exótico tag team: defeating hetero opponents with swish and flair.

Like the majority of the exóticos who had come before them, they were underhanded rudos, characters the crowd loved to hate. But they spoke openly of the LGBT experience, unheard of in the lucha world (and Mexico) at the time. The first maricón good guy was Saúl Armendáriz, a wrestler from the beleaguered border town of Juárez, who took the stage name Cassandro and became a técnico good guy and the first exótico to win a world title in lucha libre. His story is detailed in this piece from The New Yorker.

But if you’re talking exóticos in Mexico City circa now, you’re talking about Jose Christian Alvarado Ruiz. Known in the ring as Máximo, he is the beloved pink Mohawked princess from that fateful first match. Alvarado, like Armendáriz, is a técnico, an undisputed crowd favorite. Outside Arena México, Mexico City’s largest lucha libre stadium, vendors hawk t-shirts with an adorably doe-eyed anime version of the gay luchador. On the back of the shirts, in misspelled but highly legible blue cursive: “Wellcome to my world.”

I met Máximo for coffee so he could tell me the story of how he became a luchador. He arrived wearing a black t-shirt with a skull on it; his signature pink hair was showing dark roots, tied up in bantu knots, and he launched right into his creation story after paying for my coffee.

As any ardent follower of lucha libre can tell you, he hails from the Alvarado Dynasty, the three-generation family of luchadores whose patriarch is Juan Alvarado Ibarra, known in the ring as Shadito Cruz. There have been over 19 wrestlers in the family since Cruz’s time, but Máximo is the first exótico. Many of the male wrestlers in subsequent generations took names beginning with “Brazo” — -they were the arms of Shadito and wanted everyone to know it. Máximo’s father, José Alvarado Nieves, wrestled under the name of Brazo de Plata. Later in life, he changed his character into Super Porky: age increased his waistline and converted his fighting style to a more comic, but no less beloved, style.

“My first image of lucha libre was my dad in the ring,” Máximo began in Spanish. “He seemed huge. At seeing him, I wanted to be a luchador — -un rudo, strong.” But when Máximo was young, his parents’ divorce took him away from the Mexico City lucha scene in which his father was royalty, and to the Oaxacan beach town of Puerto Escondido. There he bailed early on formal education, explaining “school didn’t do it for me. Salí burro.” Literally, this translates to “I came out a donkey.”

At 15, he came back to the capital to live with his dad. He put the shellfish cooking skills he’d gained at the coast to work in a Mexico City marisqueria and lucha caught his eye again. At 20 he was attending a fight in Texcoco, a small town outside the capital, with his uncle, another pro luchador. An exótico who had been scheduled to fight failed to show up. “I told them I’d never trained,” Máximo remembered about this moment he was asked to step in. “But they told me I had it in my blood and that I could do it. I was so nervous. It was difficult but — -how can I explain? — -magic.” The sounds of the crowd buoyed him up, and after the match he told his uncle that he wanted to be a luchador.

Alvarado began training with a veteran lucha libre fighter. In the first seven months, he gained 65 pounds and passed the certification exam that all pro wrestlers are required to take, a preliminary to being able to join one of the empresas, or leagues. He took the nombre de batalla of Corazon del Dragon (Heart of the Dragon), but at the behest of the Alvarado clan, he became Brazo de Platino and started wrestling on a team with his Brazo brothers.

Something about the familiar Brazo combination didn’t inspire promoters and more established luchadores this time around. Lucha libre is so theatrical, you have to find your hook to get booked. Brazo de Platino wasn’t Alvarado’s hook.

José Luis Jair Soria, an A-list “pretty boy” (but not exótico) known as the wrestler Shocker, suggested that the struggling luchador try going queer in the ring. For the soon-to-be Máximo, the opportunity for more time under the lights was too tantalizing. “I didn’t care how, I just wanted to work.” But when they put makeup on him before the match, he had a small existential crisis. He was going gay — -for his beloved, manly, family tradition, but nonetheless…someone was applying blush and eyeshadow to his face. He was a bit jarred. “Who am I?” he says he wondered.

The audience response to his new gay character was not so ambivalent. It was so positive that Shocker and Daniel López López a.k.a. Satánico, another seasoned luchador, went to the the Worldwide Council of Lucha Libre (commonly referred to as the CMLL, Consejo Mundial de Lucha Libre), the major lucha libre empresa and recommended that Máximo be allowed in.

The name Máximo was another gambit for crowd reaction, a nod to the Roman gladiators. To finish the look, his sister Gloria Geovanna Alvarado Nava, the wrestler and sometimes Alvarado-clan seamstress Goya Kong, whipped up his now-famous skirted pink toga. In 2004, Alvarado ascended into the ring at Arena México for his official Máximo debut. Crowds continued to love him, and soon he was instructed to become a good guy técnico, a very unique move for exóticos who are traditionally thought of as devious villains.

His commitment to the role even led him to cross some of his own boundaries. Admittedly “scared” at first to kiss a man, Alvarado said, he eventually acquiesced — for the fans, of course. “The public asked for it,” he told me. “They said ‘Máximo! Máximo!’” Now in addition to various death-defying leaps from the ring onto opponents, the kiss is one of his signature moves — -and it’s a flourish that he’s paid for on occasion. Once while fighting famously homophobic wrestler Taichi Ishikari, he employed the power of the pucker and was summarily kicked in the groin.

Why do the exóticos exist in Mexican lucha libre? Anthropologist Heather Levi gives much thought to this matter in her 2008 book, The World of Lucha Libra: Secrets, Revelations, and Mexican National Identity, citing a theory that Mexican culture, even with all its machismo, is more tolerant of open homosexuality. The exóticos, or “men who have abdicated their masculinity,” in Levi’s words, duck out of the traditional chingón/chingado (fucker/fucked) dichotomy, by making their status in this binary of masculinity a forgone conclusion. Levi says when a gay luchador is in the ring, the space’s status as a masculine world is complicated. Exóticos, she writes, “do nothing to challenge the notion that a maricón is a bad thing to be. On the other hand, by their very presence in the ring, they mock the system that they are supposed to ground.”

Of course, there is a perhaps more widely asserted view of the exóticos, which is that they exist for audiences as a chance to vent their homophobia. Alvarado’s experience may bear this view out. “Mexicans, we’ve always been frightened to see a man with a man,” he told me. “In the ring, it surprises people, it’s something different.” For all the adoration he receives as the match goes on, Alvarado does suffer an avalanche of slurs when he enters the ring — -joto, puto, maricón, etc. He told me people approach him on the street and yell things at him, even when he tells them that he’s actually straight. He met his wife — -luchadora India Sioux — -shortly after becoming Máximo, and lucha fans assume they’re “just friends” when they see them out in public. But he says the most difficult part is explaining Máximo to his two and five year old sons. “The oldest asks me ‘why a skirt, dad? Why pink hair?’ I tell him that it’s a job and that in the lucha you play characters.”

And his family, for all their experience in the ring, didn’t understand it at first either. I spoke to Goya Kong and her sister Muñeca de Plata (who, as a masked wrestler, does not reveal her birth name) about how the clan accepted the news of the first Alvarado exótico. Both told me the intial reaction was shock, but: “Regardless, we support him and we love him,” says Muñeca de Plata. “Everyone knows that today he’s one of the most famous exóticos del mundo, and a huge star in this beautiful sport.” Goya Kong says she could see almost right away that this was her half-brother’s ticket to lucha fame. “He had that spark and that angle that no other exótico has.”

Granted, they’re both from the Alvarado’s youngest generation. Alvarado said that the first time his mother saw him wrestle in his pink toga, she started bawling while sitting in front of the television. Despite the fact that the family tree also boasts a man who wrestles as a psychotic clown, complete with a KISS-like mask and pointed, protruding plastic tongue, the lines around performance and real life blurred uncomfortably for her in the moment she saw her male progeny prance about the ring. “Son, are you really gay?” she asked. “We’re all jokesters,” says Alvarado of his family, “They all call me jotito. But they understand why I’m Máximo.”

It’s all very complicated, in fact. Before he became an exótico, Alvarado told me that he didn’t know a single out queer person — -he was, in his view, quite homophobic. He relies on the power of method acting: “I get in the ring, I relax myself, and I imagine I’m gay. And it just comes out, spontaneous.” The approach appears to have paid off in empathy — -after undergoing so much nasty heckling for his performative sexuality, Alvarado’s views on gay rights have changed. Two years ago, he even marched in Mexico City’s Pride Parade as a lucha libre ambassador. He said he tries to be cognizant of the LGBT experience, even as he caricaturizes it. How does he do that? I ask. “I don’t hide,” he told me, his pink bantu knots bobbing over his head.

Nasty hecklers, uncomfortable conversations, and ingrained prejudices aside, Alvarado told me he’d never give up being Máximo. The sport has brought him to Chile, the United States, to Japan. He’s gotten to wrestle alongside his father, the ultimate honor for a man who grew up venerating his dad. Máximo brings a visibly queer presence into small towns where LGBT people are rare, and he’s able to support his family with his lucha libre salary. “The best part is when you get to the arena and people ask you for a photo or your autograph,” he says. “And then they say, “Máximo, eres el máximo!’”

He had to get back to practice, so the interview was over before my list of questions were completely answered. Like: Why does he think fans react so strongly to his portrayal of a gay man? What has been his best comeback when verbally assaulted on the street? Would he advocate for having more exóticos in the sport? Does a gay wrestler automatically have to be deemed an exótico? Are there any queer women that rumble in Arena México? Perhaps most importantly, I was still deeply ambivalent over whether Máximo’s exaggeratedly flamboyant in-ring sexuality was a step forward for LGBT visibility in Mexico. The wrestler’s desire to advance equality seemed genuine enough, but can a portrayal of a marginalized group by someone outside it ever be considered anything but appropriation? I thought back to the first time I saw that pink Mohawk waving in the air, the cheers of hundreds egging him onto the final kiss KO. The light beer-aided joy I felt to see so many sports fans gleeful over his flaunting of macho norms, the way he had broken out of the villain role to be the good guy in the ring. I had to admit, it was cute. It was fun. It was a start. I wave tenderly as Máximo jogs back to the arena, the back of his t-shirt now legible. It reads: TRY ME.

Caitlin Donohue is a freelance writer based in Mexico City. She’s a staff writer at Rookie Magazine, the co-founder of 4UMag.com and liked cats before they were cool.

Adam Waito is an illustrator and musician living in Montreal. You can find more of his work at adamwaitoiscool.com and awdamn.tumblr.com. He likes cats but they make him sneeze.