Wax On, Wax Off: A Brief History of Women-Only Karate

by Mary Mann

“In the seventies men didn’t want women in the dojo,” Denise Williams told me. “Susan, my teacher, she was thrown out because she wanted to do knuckle pushups. They said, “You’ll get calluses on your knuckles and nobody will want to marry you.’”

She paused, then added: “People really did talk like that back then.”

Denise is a small woman in her sixties. She wears big glasses and smiles a lot and practices massage therapy. She’s also a karate black belt, and has been head sensei of the Women’s Center Karate Club since the eighties, but no more: this fall, shortly after the death of its founder Susan Ribner — who also helped found the National Women’s Martial Arts Federation — Denise closed New York City’s last women-only karate school.

Women-only karate classes seem, in retrospect, like the perfect apotheosis of 1970s New York. It was one of the city’s most violent eras, with approximately 2,000 murders and 5,000 reported rapes per year, not to mention an average of 250 subway felonies each week — the 4 train was known as the Mugger’s Express. It was also the heyday of second-wave feminism: Gloria Steinem founded Ms. Magazine, the Black Women’s Manifesto was published, the ERA went to Congress and Take Back the Night events began. Feminists everywhere wanted change, and while sometimes the issues one group represented clashed with those of another, one thing women seemed to agree on was the nobody felt all that safe.

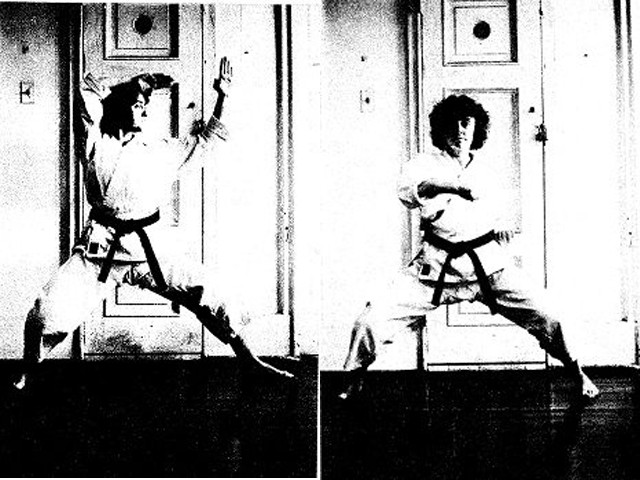

From this fertile ground three women-only karate schools sprang up, simultaneously and independently, within a couple miles of each other. Brooklyn Women’s Martial Arts held classes in apartments and at street fairs. The Karate School for Women had a storefront in the West Village. The Women’s Center Karate Club operated from the locker-lined bunkroom of a decommissioned firehouse in the West 20s, which they eventually lost due to rising rents — for most of its existence the club operated out of rooms rented by the hour.

Though this was the era of consciousness-raising — women gathering to share stories for solidarity — karate was separate from that. Instead they learned chops and kicks and blocks and a confident way of being in the world, best summarized to me by Denise’s description of kiai: staring stare someone down while shouting. “I used to be so shy,” she says. “But now, if I look you in the eyes I can just about cut you.”

Class material was the same as in male-dominated karate dojos — the difference wasn’t the what but the how. In your typical karate class you begin by tearing the ego down, but in women-only classes you build the ego up — not in a “you look great” or “reach for the stars” kind of way, but something more like “yes, your instincts are absolutely right, that guy is bad news.” Many of the women, Denise suggested, had been through some sort of trauma, and women’s karate was about trusting your gut and taking action, a pretty novel lesson in an era when marital rape was legal and women were subject to their husbands’ whims via “head and master” laws. From subway platforms to family rooms, trusting your gut is good advice that’s hard to take when you’ve been raised with June Cleaver as ideal woman.

Though they’d all bloomed so suddenly together, the city’s women-only karate schools faded away slowly and separately. The Karate School for Women was the first to go: owner Roberta Schine, among whose students was Weather Underground leader Kathy Boudin, closed up shop in 1995 to become a yoga teacher. Also in the nineties, Brooklyn Women’s Martial Arts morphed into something else entirely: The Center for Anti-violence Education. Almost twenty years later, in October 2014, the Women’s Center Karate Club finally closed its doors.

Why did women-only karate fade away?

Maybe women just felt safer, and certainly they had less time, as they were increasingly able to land a variety of jobs but still shouldered most of the household chores. I suspect the waning popularity of karate itself also has had something to do with it. American karate peaked in the eighties, but the glory days of Miyagi coaching Daniel-san in Karate Kid are long over, and strip mall karate now seems shabby next to newer imports: krav maga, muay thai and Brazilian juijitsu, plus the flashy, fast-paced combo of them all — mixed martial arts.

Women still practice karate, and they’re allowed in dojos now, but most dojos remain 90% male. This sounds intimidating to me, but for a lot of women it isn’t a problem: 31-year-old Queen’s native Cheryl Murphy — member of Team USA and the only woman on the National Karate Federation board — explained to me that she prefers practicing with guys. She has to push harder to be taken seriously, talking louder, fighting harder, challenging competitors and students alike. She sees that as a good thing. “The people who will be most dangerous to you are males,” she told me. “If I can beat them, I can beat anybody.”

We could write off New York’s women-only karate moment as a vestige of seventies feminism, like consciousness-raising or coaster-sized eyeglasses, if it weren’t for isolated instances of women-only karate classes popping up in other parts of the world more recently. Last year the Jerusalem Post reported a rising demand for women-only karate classes in Gaza, and around the same time an all-female sports center with karate opened in Saudi Arabia. Just this October the transit authority in Chandigarh, India began offering karate classes to female bus conductors, over half of whom elected to sign up in the first week.

Why the resurgence? Certainly in some places religion has to do with it, probably safety, probably also sexism. But the need for women-only karate might just be as simple as Denise’s teaching philosophy at the Women’s Center Karate Club: “I’m okay with it,” she says of the bruises she gets at the mixed-gender dojo she goes to now, “but I never worked like that. The likelihood of a woman coming to my school and having been abused — well, I’m not gonna put them through more.”

At the end of our conversation about women and karate and a different New York, Denise gave me a tip: “I think,” she said. “That CAE actually still has some women’s karate classes.”

Brooklyn Women’s Martial Arts became CAE (Center for Anti-Violence Education) largely because karate isn’t a be-all-end-all solution for everyone. To continue, they needed to diversify; now they offer violence prevention workshops and other services for women and trans people. But while they’re no longer a karate school per se, CAE still offers women-only karate classes three times a week. I wondered if it had morphed into basic self-defense, or if they’d kept the same traditional style.

I decided to check it out.

I walked to CAE on the first really cold night of winter. Brooklyn’s sidewalks were empty but for delivery guys stamping their feet on doormats and me, squinting up into the dark on 5th Avenue, looking, literally, for a sign. But CAE, like most places where people might need to hide out, isn’t big on signage. Finally I found the door and rang the buzzer.

In contrast to the windy sidewalk below, the practice room was crowded. A white-haired woman was slashing her veined arms through the air, loosening her shoulders. Two younger women — one small with an afro, the other tall and freckled — did toe-touches side by side. A girl in baggy men’s sweats bit her nails behind a swath of bangs cut to conceal. More women kept coming in after me, shedding coats and hats, until the classroom was at capacity.

You don’t need to have been hurt to take CAE karate, but at a center for anti-violence that’s who is likely to sign up, and classes are priced down for abuse survivors. Thus, all-women’s karate attracts a large and diverse group, a reminder that, while out in the world we’re divided in a million ways — class and race, religion and politics, where we’re from and how we’re dressed and who we sleep with — in our woundedness, we’re united.

This isn’t a good thing or a bad thing. It’s a complicated thing. It was comforting in the moment, though.

Class began. The women went through a traditional routine, practicing in two straight lines then sparring one-on-one. They kicked targets and blocked punches and kiai’ed with fiery eyes. Except for the instructor, nobody said a word for an hour and a half.

In an article for n+1 last year, Dayna Tortorici wrote about feminism’s shift from consciousness-raising in the seventies to information-gathering in the eighties, quoting feminist leader Silvia Federici: “One of the main shortcomings of the women’s movement has been its tendency to overemphasize the role of consciousness…as if enslavement were a mental condition and liberation could be achieved by an act of will.” In short, sharing stories is a vital component of affecting change for a large group, but it doesn’t finish the job.

On an individual level, I suspect consciousness-raising also just became wearing. We still experience the effects of this: since the seventies, the zenith of “the personal is political,” words like rape, harassment, stalking and abuse have been used so often they sound worn, journalistic. We’re oversaturated, yet the acts these words describe continue to occur, and hurt much worse than they’ve begun to sound.

This is not to say that women should ever stop telling stories, or that there aren’t new ways to do so. This is just to say that on that cold night at CAE I saw the appeal of all-women’s karate to consciousness-raising-saturated women in 1970s New York and the women in front of me in Brooklyn 2014, who’d been through their own versions of hell, fighting each other in complete silence. With their feet they broke their old stories; with their palms they built new stories, block by block.

Mary Mann (@mary_e_mann)is a writer and researcher.