Sometimes Fucking A Bear Is Just Fucking A Bear

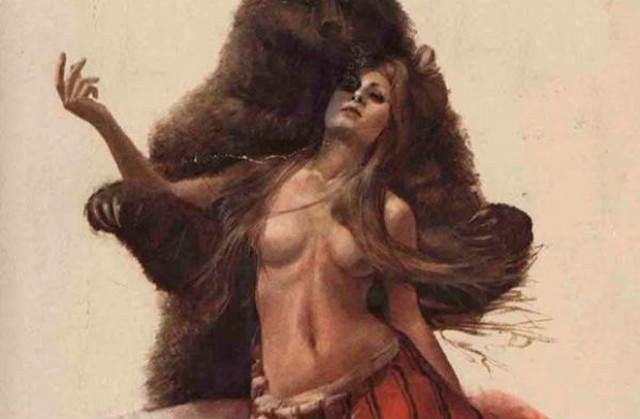

Meanwhile, in Canada, a 115-page novel about a woman fucking a bear appears.

On Friday I joined my esteemed colleagues (and fellow Pinners!) Emily M. Keeler and Monica Heisey at the National Post offices. We discussed Marian Engel’s 1976 Governor General Award-winning novel, Bear, which will be re-released on December 9th with a gorgeous new cover. I said some things that will no doubt haunt me for the rest of my life. Observe.

Monica clearly gets the best last line here (“Did you know this book was dedicated to her therapist?”) but I got bleeped by a national newspaper, so.

Believe it or not, I have more ridiculous things to say about this novel! Because apparently I have not shared enough about myself today! Follow me if you dare.

Emily was also inspired to make a bold claim in her companion review of the book: she goes ALL OUT and declares Bear to be not just a great novel, but the greatest Canadian novel of all time.

The niftiest trick Engel pulls is to simultaneously disrupt and continue that tradition — a perfect sublimation of the tensions of working to advance a living art form in a country with a hard-on for the past.

*drops every mic, but softly and respectfully, like a good Canadian*

In the video, I mention that every era and region seems to get the perverts they deserve (the Marquis de Sade, James Joyce, Freud, Bill Clinton), but Canada seems to have more than our fair share. Like, Leonard Cohen, David Cronenberg, Margaret Trudeau (God bless her), and Marian Engel, just to name a few.

So!! To briefly recap: Bear is the story of Lou, a 27-year-old woman living in Toronto and working for a historical archival of sorts. She claims to like her job, but soon we’ll learn that Lou isn’t really the best judge of her own character or examiner of her own life. She’s thrilled when her employer is awarded a home on an isolated island deep in the Ontario wilderness; as soon as spring comes, she heads to spend the season digging for notable books and items, tasked with finding a purpose for this new property. Of course, once she arrives…

…it was dark and she was tired and cold, but Homer stood looking at her uneasily, sliding from foot to foot. She wondered if he was going to touch her or denounce her…

“Did anyone tell you,” he asked, “about the bear?”

Now that’s how you end a chapter. Aspiring literary perverts, take note.

Yes, the property comes with a bear, although no one is entirely sure how it got there or how old it is; the owner of the home, “The Colonel,” brought it, and the closest neighbor cares for it, and now the property’s groundskeeper nervously tasks her with feeding and watering the chained-up animal. Far from being terrified, Lou thinks of how lucky she is. “So this was her kingdom: an octagonal house, a roomful of books, and a bear…the idea of the bear struck her as joyfully Elizabethan and exotic.”

The Elizabethans; another community of notable perverts. Anyway, to answer your question, yes, she does have sex with the bear. She never has, like, full penetrative intercourse (the bear can’t get or keep a boner, despite her repeated attempts to fellate him), but the bear goes down on her. We don’t get our first sexual encounter with the bear until page 74, which, for a novel that is ostensibly all about fucking a bear, shows a remarkable amount of restraint.

If you read Nicole’s perfect list of Every Canadian Novel Ever, then you probably have a sense for what happens in the first 73 pages: a lot of beautifully-written and compelling nothing. No, jk. The writing is truly gorgeous, more gorgeous than I expected a book about fucking a bear would, or should, be. One sentence early in the book blew me away: “The land was hectic with new green.” Seven words and limitless potential for understanding a landscape, a country, a character.

But yes, it is a deeply internal book, interested only in Lou’s thoughts and experiences and perceptions of the world around her, all of which, as you can probably imagine, are, let’s say, troubling. The first line of the book contains some immensely satisfying and psychologically warped foreshadowing: “In the winter, she lived like a mole, buried deep in her office, digging among maps and manuscripts.” A mole. Of course. But it could have been any animal here. The book is, I think, about one woman’s search for a life with only the clearest sense of purpose. Eat, shit, burrow — moles have it all figured out. Eat, shit, hibernate — well, why not? At least Lou would be spared from the burden of finding a job she actually likes, a man who she respects, a community of people who won’t disappoint her.

Because Lou is profoundly disappointed in her life, and seems completely unable or unwilling to examine her choices or culpability. She claims to like the solitude of her job, but complains that she feels aged by so much time with old things; she claims to like the solitude of her life, but complains that men seem to sense that her “soul was gangrenous,” casually dropping a reference to passionless, perfunctory sex with her boss, a man she calls only “The Director,” an affair she doesn’t particularly like but has not made any steps to end, and then another reference to a memory she shies away from, a man she picked up who “turned out not to be a good man,” references to unsatisfactory sex with women and a previous long-term relationship that ended badly. Her loneliness is, first, the elephant in the room, the subject she doesn’t want to discuss; and then later, it’s the bear in the room, her loneliness something she admits to herself right before letting the bear lick her to orgasm. Instead of examining herself, she turns a passive voice to the rest of the universe. “[R]ather, it was as if life in general had a grudge against her,” she thinks at one point, a sentence that shows the peculiar lack of agency and excess entitlement that often presents in 27-year-old women, or so I hear.

That is part of why I’m also inclined to make a bold, un-Canadian-like, Emily M. Keeler-esque statement and agree that, yes, Bear is the greatest Canadian novel ever. When we met, Monica pointed out that much of the novel reads like a straight satire of what people expect Canadian literature to be: sweeping passages about the beauty of nature with just a light sprinkling of revealing information. Lou herself sums it up when she — surprise — complains about the lack of interesting materials left to her historical institute. “[T]he Canadian tradition was, she had found, on the whole, genteel. Any evidence that an ancestor had performed any acts other than working and praying was usually destroyed.”

And yet!! Despite that genteel surface, Canada continues a proud tradition of raising and celebrating its homegrown perverts, artists who are deeply committed to pushing your sexual boundaries farther than you ever consciously wanted them to go. I mean, we (I) have made a lot of jokes about how this is a book about a woman fucking a bear, but it really is. There aren’t a lot of metaphors present here. I was mostly impressed by how much of a real bear Engel made this bear, refusing to give him even a hint of humanity, writing Lou as a woman who deludes herself into thinking she understands what an animal is thinking, that a bear could somehow love her back, could derive some pleasure from her pleasure, despite all evidence to the contrary. The bear smells bad and is kind of ugly and, I guess spoiler alert, but whatever, when Lou really does try to fuck the bear for real, he claws her back in disgust; if he could speak, I think he would say “I’m a bear,” because, duh.

But Canada’s real literary tradition is the romanticization of solitude, loneliness, isolation, our shared heritage of silent reflection. Islands, cabins, trees, bears all have the same thing in common: there’s no chance of anything unexpected below their surface. “No one can ever know each other,” Canadian literature screams, and I’m inclined to agree. Lou is delusional and there’s no way around that. She is so committed to this idea that her inability to connect with another person is their flaw, not hers, that she largely dispatches with names: The Colonel, The Director, Bear. But anyone who has ever fallen asleep beside a person they’ve just fucked and thought, with complete confidence, that they know what that person is thinking, is just as delusional. We don’t know each other and we can’t know each other, is the lesson Canadian literature wants to teach me, an entire canon of characters living in their self-imposed exile, proud Canadians holding themselves separate like millions of little islands hosting millions of tortured self-discoveries.

Another gem of a sentence appears early in the book: “She thought of a man she knew who said it was impossible to find a woman who smelled of her own self.” I’m assuming this man is speaking of soap and perfume, which, ok, thanks for your opinions. But Lou is moved by this statement; she wants to smell like herself. That’s her secret mission, even as she speaks endlessly about her mission of finding out who the owner of the house was, finding the value of their materials for her institute. Yet by the end of the book she’s bathing the scent of the bear off her skin so that no one notices how close she’s gotten. This supposed journey of self-discovery doesn’t bring her closer to her own scent. Perversions are nothing without a sense of purpose.