Size Matters: An Interview With Anne Ishii

by Chris Randle

In Our Lady of the Flowers, Jean Genet posited: “A man who fucks a man is twice a man.” His bluntness invites multiple interpretations — is the man becoming engorged, or dissolved? Gengoroh Tagame’s intense, sadomasochistic porn comics test that hypothesis to extremes, as if trying to break maleness itself. The book designer Chip Kidd discovered them during a trip to Japan in 2001. This was gay manga, but not the yaoi or “boys’ love” most familiar in North America, with its epicene beauties primarily drawn and read by women. (The female counterpart is called yuri.) Butch-looking, often hairy, the men had precise taxonomies of size, from gacchiri (muscular) to gachimuchi (muscle-curvy) to debu (fat).

Kidd’s initial entreaties went unanswered, but some time later, working with Graham Kolbeins and Anne Ishii — a former colleague at the publisher Vertical — he tracked Tagame down. When the first authorized English-language collection of his comics came out last year, co-edited by that trio, The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame was quite literally bound inside the Japanese wrapping called an obi.

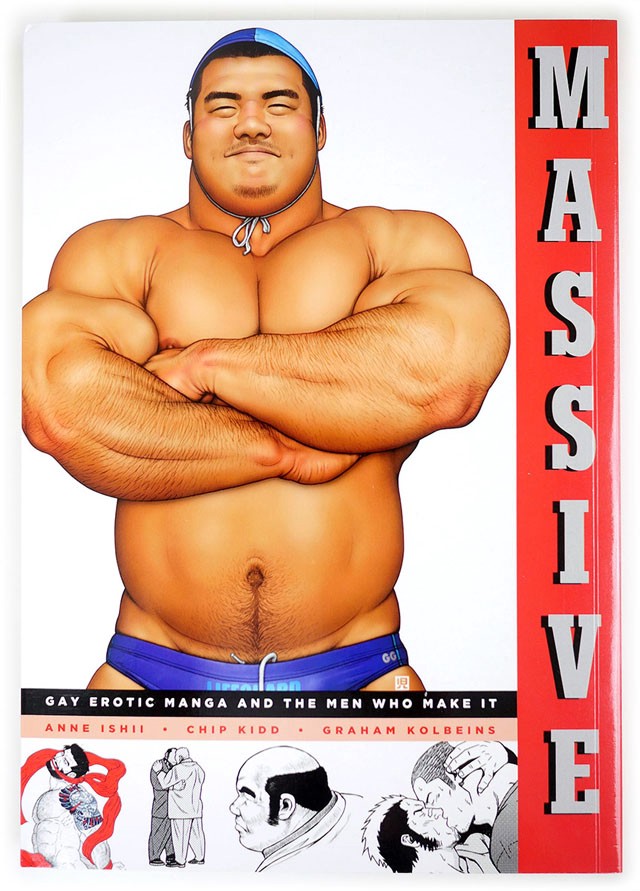

Tagame is a touchstone for the subgenre sometimes known as bara, both through his own work — he helped found the influential magazine G-men two decades ago — and his efforts to preserve the history of Japanese gay art, which flourished in ancient forms before the Meiji regime strove to modernize such “barbarism” out of existence. In their new companion anthology Massive, the editors give some context to his fellow cartoonists: the gender-norm-mocking gag comics of Kumada Poohsuke, Gai Mizuki’s porny fantasies, Jiraiya’s hyperreal beefcake.

I wanted to interview Ishii about it ever since Tagame guessed his fanbase might be half female — his earliest comics were published in the yaoi magazine June, a name punning on Jean Genet’s. Why can’t gay manga for men be for women too? As Tagame chuckled to me last year: “I actually really love taking, you know, the guy who says ‘I’m a real man!’ and saying to him: ‘Maybe you’re a woman.’”

Do you remember the first time you encountered the kind of material in Massive?

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, it began with Gengoroh Tagame’s work, which I was translating for Chip Kidd a million years ago. That was my entree. And then from there it was just other people who were fans of other artists, meeting people like Graham [Kolbeins]. I guess the first person after that was Jiraiya, and actually Kazuhide Ichikawa, mostly because he speaks English and is pretty prolific online, he was easy to find. And then a lot of the other artists we found through more research, but Tagame was my first.

What was your reaction to it at the time?

Well, with Tagame’s work, my first reaction was “what the fuck am I looking at,” because it was so outrageous [laughs]. I guess it started when Chip showed me his books, so I have to say it was not as shocking as all that, because there was actual narrative and it was packaged in a nice way. But I followed to the cookie crumbs to his website, and then I found his illustrations, which were just so extreme. So there’s a bit of shock and delight in all of it, but then because I was translating it wasn’t so much my reaction as — how do I interpret this, how do I translate it? And that was interesting, learning a lot of that language.

Had you been a reader of yaoi or anything like that at all before then?

No, that’s the funny thing — I have to say, as far as my tastes in manga run, it’s definitely not — I’m not really a shojo reader in general and I wasn’t reading any yaoi or BL ever. So I was totally unfamiliar with what we call slash fiction here, or over there the interpretative doujinshi market. I didn`t know anything about that until pretty recently. My initiation into a lot of manga is not as a reader but a translator.

Can you tell me about the process of selecting and tracking down all these different artists? Some of them are very private about their personal lives. Did you have any mysterious Deep-Throat-style meetings?

[laughs] It’s not that cloak-and-dagger. The privacy issues that a lot of our artists have aren’t about getting exposure, just protecting their personal identities. They love the exposure for their work — actually, almost all of them are online and have active personas on Twitter and on blogs and Pixiv and things like that. Half of them actually sell their stuff online. I think they’re glad about the exposure, but partly it’s a language barrier and partly it’s about protecting their identities. As far as the process of finding and selecting them, we cast a pretty wide net across the field of gay artists.

We depended quite a bit on Tagame introducing us to some of the people that we knew on our own, and with others Tagame recommended specifically that we reach out, because we might not have heard of them but they were worth checking out. There’s an artist Fumi Miyabi, who was not someone we really knew until Tagame said we should be checking him out, which I’m really grateful for. Other artists we talked to wanted to participate but it just wasn’t gonna work out at this juncture, because we couldn’t get interviews or enough material from them in a timely manner. This easily could’ve been up to 15 artists, but the nine we chose fit our timescale and our editorial limits, as it were. I also think they represent a pretty diverse range of comics styles, so it’s not just erotic or it’s not just long-form.

I was struck by that, actually, because obviously the first book was all Tagame, and it makes sense to me that he found that big following outside Japan — his work is kind of classical, in its fetishistic way. Whereas [Kumada] Poohsuke, in this book, makes what are basically gag comics, and the humour is very much about modern Japanese culture. Or there’s, um, I can’t remember the artist, but there’s that amazing story about the straight-identified schoolteacher who gets so uncontrollably horny that he just has to let the janitor suck his dick, which is an all-out porn scenario.

Totally.

And it’s interesting that Tagame — not only just because of his popularity, but also because of the way that he’s researched the history of homoerotic art in Japan — has sort of become a locus of all this.

Yeah, I think his role in the creation of the gay art canon in Japan can’t be overstated. He is not just responsible for the biggest tome of work — he’s been a really important archivist too, I think…And it’s lucky for us that he was just bilingual enough that his work communicated to a few key people back in the day and then that came our way.

It’s also…this stuff goes back so far, into a pre-modern understanding of sexuality, but a lot of it was deemed to be “degenerate” during the Meiji era, and suppressed in various ways.

I think you’re right, and I think Tagame’s pretty self-aware about the role of history when it comes to conveying erotica to other readers. Some of our artists, with all due respect, have created their art in a bubble, because they know who their audience is. Which is great, because then it becomes something that’s just full of their own passion, but an artist like Tagame distinguishes himself by considering the universal audience, and in that sense has to keep context in mind. History is always in the background, even if it’s a modern setting. He’s just done such a great job contextualizing inside and outside of his work, you know?

I’m assuming you did most or all of the translation work, and there’s a really fascinating section where Graham Kolbeins talks about the word bara, which is what all this manga has been most commonly known as in North America. But a lot of the artists don’t identify with that term at all, because it’s like a reclaimed slur, right?

Yeah, it’s a false positive for sure. I guess that happens a lot between languages, so I don’t think it’s the fault of any one culture or person, but it’s definitely taken on a life of its own in North America and in Europe, actually. The broad West, for whatever that word is worth. I know that for a lot of the artists we spoke with — I don’t think anybody was offended by that nomenclature, they were all just confused. It would be like if we started to re-appropriate “pansy,” which is fine, except that’s not a word whose currency was so long ago that — to fix that problem almost seems 20 years too late, you know?

Yeah, and in Japan they have these identifiers with no precise equivalents in North America, like the whole “muscle-curvy” thing.

Actually, it’s funny, I think one of the reasons bara took on any currency was because it had a vaguely exotic feel to it, because it was untranslatable, or we thought it was untranslatable. People preferred to call that bara because it wasn’t a Western word, except meanwhile there were plenty of untranslatable Japanese words that just weren’t gaining the currency for some reason. And another reason is that these words all describe corpulence, but there isn’t an umbrella term for all of that, the concept of referring to men by their size is the lexicon for gay erotica. Things like “muscle-curvy,” or “muscle-fat,” or “muscly-muscly” or “muscle-hairy.” There’s so many combinations of that.

Were there any specific challenges in translation, whether because it was slang or some other reason?

Absolutely, yeah. I mean, slang is sort of hard, but I think it’s also popular culture. A lot of our artists make references to things that are part of Japanese popular culture mainstream that would never make sense here, so I would have to just make up my own correlation. This isn’t in our book, but in a translation I did for Takeshi Matsu for a different title, he makes heavy references to a bunch of famous Japanese comfort foods. In that situation I decided to just leave it as-is and italicize Japanese dishes. These are foods that none of us would consider comfort foods. That’s the hardest one, because I have to use my own creative judgement and come up with different corollaries. You know, their miso soup here would be something you only get at a sushi restaurant, but there it’s like part of breakfast, so I can’t really translate that, right? I have to give the reader the benefit of the doubt and hope they just figure it out. And that’s the great thing with manga, even if the words don’t have exact translations the images always mean the same thing.

This comes up again and again in the mini-profiles of the artists — there are fans who translate this work on their own, but they’re also releasing it for free, which is giving a lot of the cartoonists even more economic anxiety. Do they have a common position on the whole scanlations issue?

Well, it’s funny you should bring that up, because we had several artists tell us they weren’t opposed to it, but they didn’t want to be on the record, because as a community it would not behoove them to fall out of line in that argument. And of course in a perfect world there aren’t scanlations and everybody profits off of their own art or whatever, but that’s just not a reality. I think it’s sort of like the way a lot of writers in North America feel about Amazon, where it’s a necessary evil. I know even our own book wouldn’t really be sustainable if there weren’t a huge underground community of people reading scanlations. This isn’t to say I think they should all be doing scanlations, but we know what we’re dealing with, and it would be a little bit naive not to. And in that regard we do have a few artists who are not opposed to it whatsoever. If you read our book carefully you’ll know which ones they are, because we don’t quote them saying that they hate it, but the ones who are opposed are very vocal about it.

Other people have more ambiguous or nuanced positions on it. Like, [Seizoh] Ebisubashi, who did that story you just mentioned about the 5th-grade schoolteacher who identifies as straight but fucks the janitor [laughs], I think that’s kind of an apt metaphor for how he feels about piracy. He doesn’t self-identify with it, but will certainly fuck with it. He has said on his own Tumblr, like, let me know what you guys want for free and I’ll try my best to provide as much of it as I can, but beyond that I really do need to make a living because of this, so please endorse my work by actually buying some of it. He’s been very generous with content on his Tumblr while embedding a lot of cues to go buy what is pretty affordable digital comics. And I have to say personally that that’s probably the best way to go, because you can’t really fight the hunger for the content.

Yeah, it must be difficult for a lot of them, because it’s not just some guy ripping a CD to torrent it. People are putting actual work into this out of love for their comics. It’s a tangled, fucked-up affection, I guess.

The weirdest part is the person who actually profits off of a scanlation without even getting in touch with these artists who are otherwise pretty visible. That’s the part that’s a little bit unsavoury. I understand when people want something they’re going to get their hands on it, but it’s not that hard to get in touch with some of these [cartoonists], and they’re not necessarily opposed to the exposure. At a certain point, if you’re gaining more than the original artist then that’s a problem.

It seems kind of analogous to the way queer bookshops in North America keep closing. I think you mentioned that they sell these books at gay bars in Japan, which is an interesting…economic model, or strategy? The bars or clubs or other spaces there, they seem more like clubhouses, almost.

Yeah, I think you’re totally right. That’s a really interesting corollary, actually, because as a business model it’s pretty unique. I’m thinking about this for the first time, but wondering out loud if that would be possible here, you know? If gay bars would support small libraries like that.

Is there a story about when you went to that Big Gym — which is an amazing name — the Big Gym store, and they weren’t very welcoming?

Right, right. Yeah, I tried to go into a Big Gym in Shinbashi, which is notoriously a business neighbourhood, it’s really close to the so-called Wall Street of Japan. I understand now in hindsight it’s probably catering more towards businessman who are in the closet, but I walked in there and the clerk was like: “What are you? Are you female?” I tried to pull the tourist card [laughs], like, I don’t know what I’m doing here, but it all worked out. And the best part was, even though he was trying to get me to leave the store, when I finally made my purchase he slid some party flyers into my bag. “Please don’t come back, but don’t forget we have a party on Tuesday night!”

I actually just met another Big Gym manager, and the store is very sympathetic to all consumers of gay media, for sure, but that particular branch doesn’t let women in their store. I talked to another manager who said that frequently they get women coming, especially when a new Tagame book has been released, they’ll come to the store and come right up to the door and not step in, just hand a note to the clerk and say “this is what I’d like to buy and here’s my money, can you…?” They’ll just wait by the door for the clerk to make the transaction for them [laughs]. We talked to yet another manager of a gay bookstore who was saying they have these rules that were imposed to protect their consumers, but it’s beginning to feel outdated in the 21st century. Girls are certainly not the enemy. Maybe the censorship police, but…

Do you have any theories about why women are drawn to some of this work? Hannah Black wrote this really great essay about her youthful identification with novels by gay men. She wrote — I’m just quoting here — she wrote: “I read them as a lesson in masculine pleasure, and as a revolt against the unpleasure of femininity…In my image of gay men, distorted by longing, I found masculinity in a form I could bear.”

That’s a really well-put interpretation. That’s beautiful. I don’t really have a theory as to why women are attracted to narratives about gay sex, but it is very determined, what straight women go for. Or actually gay women for that matter, many of whom have told me that they are big fans of Tagame’s work, for example, but not necessarily of some of our other artists. Even though a lot of women do like man-on-man sex in comics, it’s not all man-on-man sex comics. So, like, obviously there’s yaoi and BL, which is created almost exclusively by women, but even in the hardcore realm — it’s not necessarily Jiraiya, for example, most of his fans are dudes. Tagame’s big.

Maybe one of many themes that translates to women is — not just the idea of displacing body issues or displacing gender roles, but getting down to that nutty core of desire. I don’t think Tagame’s work is just about men loving men, it’s really about how dark desire can be. And that’s different from the humour of Poohsuke’s work or the absurdity of Ebisubashi’s work or the celebration of male corporeality in Jiraiya’s work. That’s a theme I think women gravitate towards.

Yeah, I’ve read that Jiraiya’s fanbase is almost entirely male. But the Jiraiya clothing you’ve done through Massive, the licensed apparel, women really seem to love those. I feel like the photorealistic bro-ness of his illustrations almost makes them — it’s this extreme of masculinity that’s kind of camp, and thereby friendly. Like, I’ll wear the classic Jiraiya sweater, and people will, well, sometimes they ask me if it’s a Drake reference. Or they’ll be like, “Are those guys famous?” But more often they’ll ask something like, “What’s the deal with that great sweater,” and I might say “They’re just really good friends.”

I think you make a good point that women love our clothes, but with that one specifically there’s Jiraiya the mangaka and Jiraiya the illustrator, and those are two different things. His comics are really good, don’t get me wrong, but a completely different ball of wax. The victories in Jiraiya’s comics aren’t quite as difficult as, say, Tagame or Ebisubashi’s work, but the illustrations are straight-up pin-ups. And I think for a lot of people, regardless of gender, those pin-ups represent something we all want out of life, a big cuddly dude [laughs]. It’s just very comforting. I know for me, looking at illustrations by him, it just feels nice on the eyes, it’s so aesthetically pleasing. It does challenge a bunch of notions about what the Asian male body should look like, but as an Asian person that’s actually really exciting.

As far as the “Best Couple,” the classic Jiraiya image, that blue sky background was Graham’s idea, and he might have been thinking of Drake in the very dark recesses of the dark of his mind, but Jiraiya’s original illustration and accompanying subtitle was “the perfect couple,” and his idea of the perfect couple was that image. It’s funny technically speaking because with his illustrations, which are all so magnificent, he doesn’t do backgrounds, only the subjects. So that’s neat too, because he’s talking about a subjectivity, not a universe.

A bunch of his images are composites, right? Or he’ll take an idea for one body part from a photo somewhere, so it’s this totally unreal Frankenstein of a person.

Right, but in a strange way it makes sense when it’s put all together. In our interview, he said the thing he was most scared of was being on the wrong side of the uncanny valley [laughs]. And I think he does a good job of staying away from that weird Final Fantasy composite. That’s where his talent is, I think, in his ability to do something that shouldn’t work but succeeds.

Can you tell me about the genesis of Massive, not the book but the company?

Um, yeah. The short of it is that Graham and I needed to make money [laughs]. We were talking about this book deal, and did the math, and realized we weren’t going to make any money — certainly not off The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame and not a lot when we did Massive. That has nothing to do with the generosity or paucity of our publishers but the industry in general. So we said, “let’s just start by making some T-shirts,” and then Graham’s imagination has just been so fruitful. He keeps coming up with ideas for extensions to the clothing line, the Opening Ceremony collaboration was his idea, all of these things.

With the Massive-branded Tenga, the sex toy.

Oh my god, the Tenga. That was actually all Opening Ceremony, I was really surprised, but they have an existing partnership with Tenga. The funny thing about that too is that Tenga won’t sell it in Japan. It’s a Japanese company and it’s Japanese art, but it’s only available at Opening Ceremony in New York and on our website [laughs].

I had never heard of it before then, and I thought the whole deal with Tenga was fascinating in that the toys are all really abstract. They don’t try to mimic a specific body part or anything.

I hope not, otherwise humans would be out of a job. But yeah, Massive started that way…Once we started doing the clothes, we realized we could be bigger than just T-shirts. So now our focus is on importing more comics and becoming a sort of clearing house for more queer comics in general. On this recent trip to Japan we talked to editors of other forms of queer comics — actually, we talked to some people about straight art that has to deal with issues of the body and falling outside of heteronormative notions of identity. Eventually we want to be able to broker more content and less in the business of manufacturing clothes.

So were you looking at yuri and that kind of thing?

Oh yeah, absolutely. Not saying that we have plans for that yet, but we’ve been hugely interested in that for a minute now, definitely.

This is totally speculation on my part, but I feel like a lot of the explicit yuri comics in Japan are drawn by men. Is there an equivalent to the work in Massive, where it’s comics about women drawn by women?

Yeah, I don’t know the community that well, to be completely honest, but they do exist, and manga editors are more and more interested in finding these kinds of outsiders right now. I think the market for things like yuri and yaoi, or for that matter shonen and shojo, is so competitive that it’s become pointless for a lot of editors to pursue that market, in the same way that a lot of independent publishers have given up on superhero comics. Offhand I’m thinking of a handful of artists who identify very openly as lesbians and write about their experience, that’s obviously interesting to us. But I don’t know what the Big Gym of that community is, or the G-Men of that community. It probably exists, but I don’t know what it is.

Do you have a sense of the demographics of the Massive customers?

I can’t say, like, it’s 80% this or whatever, but I can definitely say the most surprising — or not the most surprising, almost the most tragic market, is the Japanese one. We have a big Japanese market, which I find kind of ironic given that a lot of this content obviously comes from there. I don’t think we’re mainstream, but we’re more mainstream than a gay bookstore in Shinjuku Ni-chome. That’s not to fault those bookstores, but that’s been the surprising market. Or the market we have in Asia in general. We frequently get orders from China with specific notes, like “don’t describe the content,” or “please package this discreetly,” and I’ve heard from one fan, this woman out of Shanghai, that she knows people who’ve been arrested for importing or buying these things. Not our things, but gay content in general. So that’s kind of a weird place to be. I enjoy it, I like providing that service, but it seems a little tragic.

It’s interesting that you mentioned a lot of your customers being from Japan, because homoerotic material is not necessarily legally persecuted there, but from the interviews with certain contributors in the book, and other stuff that I’ve read — at least outside of the big cities, Tokyo, Sapporo, et cetera — it won’t be a threat if people find out you’re gay, they might just consider it gauche, like a social faux pas.

It’s so tricky, because — like you said, it’s not that it’s frowned upon per se, but it is — people don’t wear their sexuality on their sleeve, literally or figuratively. But I guess that’s like most of America too. The thing with these products is that people might not necessarily be public with it, for some of them owning it is enough. In other ways, each time I go to Japan I’m astonished by how much more open it is where sexuality is concerned. What’s considered obscene has changed a lot over the last 15 years, I’d say.

And over here, queer people — maybe a few people who don’t identify as queer, too — visibly ignoring gender roles, they still get a lot of shit for it. Like, if you’re not the archetypal straight-acting gay man. So I thought it was great that Poohsuke specifically does these hilariously confrontational gender-subverting antics. You mention in the book that he’s a huge fan of…I can’t remember the name, the theatre where a woman plays every role…

Oh, Takarazuka.

Yeah, the all-female theatrical revue, where half the roles are women in drag. Or he’ll put on makeup and a skirt and do a performance involving the J-pop group Perfume.

Which is funny, because Takarazuka is kind of a response to kabuki, notoriously all men. There’s an action and a reaction, you know? Poohsuke’s great, he’s a seventh wonder of the world in that sense. He’s doing a lot of interesting things on his own. When we saw him on this last trip, he said he’s really into zentai right now, which is the full-body latex suit. I guess there’s a group of fat guys who get into the zentai suits, and they’re not all necessarily male? Because they can’t see each other they’re allowed to be women as well. He was just telling us how exciting it is to finally interact with fat women without feeling weird about it [laughs], because he can’t see their faces or their genitals. I thought that was amazing. Talk about breaking out of form.

I asked [cartoonist/friend/collaborator] Mia Schwartz if she could think of any questions I should ask you and she was just like, “Ask her how much she can lift!”

[laughs] Wait, did I tell her that I lift? Is she a lifter? Now I have to make up a number that seems plausible but isn’t — oh my god. I can lift a lot, I’m actually really strong. I can princess carry my fiance across a room.

I got this image that you didn’t even go to the gym, you just read all these muscle-dude comics and became super buff through osmosis.

Exactly, I became strong through reading gachimuchi porn.

Chris Randle is a writer from Toronto. His work has appeared in Hazlitt, Slate, the National Post, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Little Brother and also Opening Ceremony’s blog. He makes the comic Charivari with Mia Schwartz for Adult magazine.