Love Your Neighbor: An Interview with Goldie Goldbloom

by Tova Benjamin

I first met Goldie Goldbloom when I was in fourth grade. She was sitting behind me in synagogue and touched the sleeve of my sweater, saying, “What a beautiful cardigan!” It baffled me at the time; I didn’t know what the word “cardigan” meant.

I started this interview by asking Goldie if she remembered the first time she met me, and she had a different memory. It was during Sukkot and both my family and her family were eating a festival meal at a neighbor’s sukkah. I was just a baby, but Goldie said she remembered looking into my eyes and making some gesture about the food being terrible and the world being corrupt, and she says I looked at her from my mother’s shoulder in a way that suggested, “Well, at least there’s a shoulder to lean on.”

Though she was a fixture in the Chassidic community I grew up in, I didn’t have another conversation with Goldie until I was well into my teens. I was beginning to stray from the Chassidic traditions, and Goldie had just come out as queer, something our community could not tolerate. I found Goldie’s home to be a sanctuary where I was always welcomed into a loving family of writers, big hearts, and outcasts.

Over the past few years, Goldie has worked hard to create safe spaces where queer Jews can connect, share their stories, and exist outside of a community that wants to ignore them.

In addition to being an incredible inspiration and making the best Shabbos meal you’ve ever had, Goldie is the author of several wonderful books, including The Paperback Shoe, which won the AWP Novel Award, and the short story collection You Lose These. This year she received both the National Endowment for the Arts and the Brown Foundation Dora Maar Fellowship. Though I had lots of questions about the many, many writing projects Goldie is involved in, we spent a good portion of our interview talking about the community we came from and why her work is so essential. Most importantly, we talked about her blog and soon to be book, Frum Gay Girl, where she collects anonymous interviews with Jews who are secretly queer in their ultra-Orthodox and Chassidic communities.

I’m just going to jump in and talk about Frum Gay Girl here. I was interviewed for your blog in its early days, and I know since then you’ve gathered the narratives of secretly queer Jews — -some from our community, but many from various different Chassidic sects. I want to talk about the necessity for secrecy for those who aren’t familiar with the social customs. Why is it so necessary that these stories remain anonymous, and how do you respect the identities of the people who speak with you?

That’s really several questions in one.

Do you want to begin by talking about how Chassidic communities function?

Sure. Chassidic communities function in a very Eastern sense. The individual and the individual’s rights and needs are not as important as the needs and the rights of the community as a whole, and in a smaller sense, the family. Most North Americans are more familiar with the Western value of individuality. Both cultures have long histories and both deserve respect, I want to say that upfront, because it is easy to judge when what you hear or read doesn’t fit your worldview.

Chassidic communities tend to do a lot of policing for homogeneity, because, as I said, the primary value is community rather than individual. And as such, differences in dress, speech, belief, and education aren’t typically welcomed. This is a generalization and like all generalizations there are exceptions. But as a general thing, within Chassidic communities, you could expect to see many people dressed in highly specific and similar ways, many homes which are the same in fundamental ways, and schools and communal organizations that reinforce that sameness.

And what about those that have trouble fitting the mold?

Well, along comes someone who doesn’t quite fit the mold. Unlike in Western culture — -“Oooh! How cool! This kid is so different! — -within Chassidic communities, this difference is seen as threatening to the community norm — -“Oooh! This is dangerous! This will destroy our community.” The idea of danger gives rise to fear. The community watchdogs are alerted, and they spring into action, trying to “herd” the person who isn’t fitting the norm, and return them to the community. If that doesn’t work, then the person is often cut out of the community. Typically, community members do not want to leave. And they are afraid of these watchdogs.

I’m interested in that difference you drew between what is celebrated in Western culture and shamed in the Chassidic community. Because when I left the community, many of the things I was shamed for in the community (being “different”) were celebrated in certain secular circles. But someone queer may not be celebrated in Western culture either. The Chassidim are typically secluded and closed off from Western culture, but a part of me wonders if the extra repulsion and cruel treatment queers receive is influenced by more than just fear for the community…

So, when it comes to queer Jews, it’s an interesting situation. Jewish views on sexuality were very heavily influenced by Christian mores in the Middle Ages.

Whoa. Tell me more about that!

Initially, there was a fair amount of discussion and, if not acceptance, at least acknowledgment, that there were a certain number of people within any given community who were queer. In the Talmud, Rambam, there are long discussions about trans people, intersex individuals, lesbians, gay men. One of the things I really enjoy is the very casual way lesbians are discussed, as if, of course! There are lesbians living down the road.

Anyway, along comes the Middle Ages, when there was a very intense attitude in the Church about sexuality and homosexuality in particular. Some of that attitude seeped through the ghetto walls. At that time, the conversation about queer people really disappears from Rabbinic literature, and we arrive at “modern” Jewish life, where there is a fairly entrenched fear and dislike of queer people. Instead of the (much) earlier attitude of “oh yeah, those people, we know about them,” there is “those people don’t exist.”

So, now, step into our culture…you’re a queer person and you don’t seem to fit the cultural norm of the community in which you grew up. There are NO narratives for how you should live your life because you “don’t exist.”

Growing up as a kid, I don’t think I had ever really heard of a gay or queer person before, especially not a frum (devout) one! And that’s the most important thing your blog is doing, which is not only addressing all these issues within the community, but also simply stating that queer Orthodox Jews DO exist.

Right. There’s that great interview with Chassidic Jews on Oprah…

Yes, where they avoid the question entirely.

She asks these four women what they would do if their kids were gay and they completely freak out and deny even the existence of such people within the community. That’s really sad.

I think I even remember them calling it a theoretical question, like an issue that just wouldn’t ever come up…

Even the lowest numbers of queer people within Chassidic communities would put the population in the high tens of thousands. In the Oprah video, the woman called it “very extreme” and said “it doesn’t happen.” Really, no one talks about it.

People tend to justify not talking about queer people because, in general, they don’t talk about sexuality at all. If you aren’t talking about so-called “healthy” or “normative” sexuality, then why would you talk about what the community regards as “deviant” sexuality? It’s sad. You have these young kids growing up, looking for role models, and they pretty much don’t exist. They might be there, but they are invisible. Or they have left because they’ve been chased out. Or because they felt there was no room for them…or because it was dangerous…

In what ways does it become dangerous?

So, remember the watchdogs? Just like in any community, there are always individuals who like to take matters into their own hands. In Chassidic communities, there are people who will do things like throwing stones at people in Meah Shearim, or burning Israeli flags. It’s hard to explain to someone who has never lived in a very powerful and nurturing community what it’s like to have that threatened. The closest example in the Western culture might be loss of a job, rather than loss of family, because many people have already left their families. So, if you had an extraordinarily well-paying job, where everyone was nice to you, and if you got sick they brought you meals and the entire workforce came to all your parties and they were all rooting for you and had your back and you had special cheers and songs and dances and foods and handshakes and uniforms and you knew all of their names and they knew yours….

Right, most people just don’t understand. They say, “ok, then why don’t you just leave?” But this community that may be tormenting you is also the community that loves you and has taken care of you. In addition to losing the handshakes and dances and uniforms, you lost a big part of your identity and have no idea how you will be outside of the community, or if you’ll ever find another one…

Exactly. So let’s say someone comes to you one day and says, “Listen, if you don’t stop limping, you are going to lose this job.” Well, it would seem like a small thing and you would probably do your best to lose the limp. And then, a few months later, they come to you again and say, this light pink shirt is not okay. Please only wear the dark pink one or you’ll get the sack. And again, it’s a small thing, and you get into a pattern of following the norm, because after all, this job is so freaking amazing, and once in a while, you see someone get the sack, someone who wouldn’t conform, and you think, what an idiot! You don’t get it. And the more times you see someone get fired, the more you cling to your own position, the more you are willing to give up in order to keep it, because now, you’ve bought into the system. Now it’s YOUR system.

Exactly. I remember in elementary school when I saw all these older girls getting kicked out and shamed for watching movies or texting boys and I was like, “Is it so hard to just not text a boy?”

But it wasn’t just that, right? Who knows how many other things these girls had been asked not to do, until there was one thing that felt like it cut to the heart of who they were and they simply said, no, that’s too much, you are asking too much.

Of course the same thing eventually happened to me, and my friends would say, “Just wear a longer skirt! Or just don’t watch movies!” But they were always asking for more than just that.

Yes. At some point, the queer kids will have been responding to community pressure for maybe ten or fifteen years, and it hasn’t exactly felt like pressure, but eventually this pressure begins to edge closer and closer to the core of who they are, underneath it all , and there comes a moment when they are asked to give up something they can’t give up…

Anyway, back to the danger: in the moments when the kid is still trying to conform, typically, they will be asked several times to conform, and they will do it, each time afraid of what will happen if they don’t. And in the real Chassidic world, if they don’t, it can have a range of consequences, from getting kicked out of school, not receiving service at hops, getting kicked out of your home or family, not being able to get married (a huge one for most people), making it so that your siblings can’t get married or end up with bad matches, emotional and physical violence against you or your family.

Are many of the people that you interview still in the community and not openly out?

The vast majority of people I interview are completely closeted. Most of them have chosen not to leave the community. Many of them are married to opposite gender partners. Many of them have children and have homes within the most right-wing communities in the United States, Europe and Israel. Typically, when Chassidic people leave or are pushed to leave their communities, they do not hang around the edges, and remain partially observant. Usually they have suffered devastating losses and want nothing to do with their communities. Some of them have lost custody of their children, some of them have been told they can never talk to their family members again, some of them have lost friends and lovers, some of them have had their property destroyed.

Which is where the need for secrecy comes in.

Yes. When I came out, I was very aware of everything I stood to lose, and it was terrifying. The reason it is terrifying is because it’s not just in your mind. You’ve seen it happen to person after person and you know it could and probably will happen to you too. I do not blame anyone for not coming out in the Chassidic community.

Also, you didn’t want to leave the community or stop being religious, right?

Right. So, in this it turns out that I am somewhat unusual. I did come out, but I didn’t leave the community and have maintained my spiritual practices and connection. Despite opposition from some quarters, and of course, the invalidation of being constantly told that I am no longer religious and can’t be trusted.

I’ve noticed that most of the queer Jews you talk to for the blog love being frum even if they don’t love their communities.

There ARE lots of queer Orthodox Jews, yes, of course, and there are some who are out.

As someone who practically lived at your house, I know you keep strictly kosher, and keep Shabbat, etc. But because you are queer, many people would say that nothing in your house was reliable. When your kids were still in Chassidic elementary school, they weren’t allowed to have friends over right? And people practically boycotted your family….

Yes, my children could not have friends over. I was told that my home couldn’t be considered kosher and my Shabbos couldn’t be considered Shabbos. I have been repeatedly told that I am not frum, or not frum enough, and people continue to act surprised that I keep strictly kosher, and keep all of the Jewish holidays. The only surprise is that with the amount of disapproval and rejection that I do keep kosher and Shabbos.

I once interviewed a young woman who was part of one of the most stringent Chassidic groups and initially, during our calls, she told me that everyone was being supportive of her queerness. I was very surprised, because I worked for years in that community and I know first hand that it is a community that is unlikely to be supportive… on one of our calls, her mother was screaming in Yiddish nearby, and asking, “Who are you talking to? Hang up the phone, you crazy person!” The girl continued to say that her family was being supportive, her community, her best friend, her teacher…but then, one day, she went too far, I am not sure what she did or said, but bang, just like that, she lost all support and began to leave the community in practice, belief, and in actuality.

Oh that’s so sad. That makes my heart hurt for her.

In some ways, the Lubavitch community that I am a part of has taken some steps to be more inclusive.

Once in a while, I get a call from someone. There are certain families that will take the risk and come over for a visit. Usually they are people without kids, or with grown kids, because most people with young children don’t want their kids “exposed to my lifestyle.” Ha! I might turn them into lifelong gardeners or readers or something scary like that.

I know when I was interviewing for your blog, I was very paranoid about who would read it and see it. Why do you think coming out as queer is so terrifying?

I think many young people (and not so young people) feel that being queer and being Jewish are mutually exclusive. Because they haven’t seen or heard of any queer Jews in their communities growing up…so, you’re either queer, or Jewish. That announcement carries another unvoiced one within it: “I am not going to be Jewish,” or religious, or spiritual, or observant, or however you’d like to phrase that. Coming so soon after the Holocaust, announcing to your parents and community that you are leaving the community is really radical. And that’s all tangled up with the “I’m queer” announcement.

And so in addition to trying to say “we exist,” do you think your blog is trying to present another option? To explain that “orthodox” and “queer” aren’t mutually exclusive, and that it is normal and can be done?

Absolutely. That is absolutely my intention. Without role models within the community we are doomed to keep on repeating the mistakes of the past. Think: suicide, self-harm, sad lives lived unknown, homelessness, death of a spiritual life, loss of family and community…

Right. These are super important reccurring issues for queer youth in the community. But I think your blog engages in a question of Halachah (Jewish law) and what community means — -would you agree? Because the reason these laws and customs exist in the first place is to keep the community together. There are in fact, many instances in which the law must stretch itself to preserve the idea of community, as alienation is to be strictly avoided. I want to talk about the freezing of that theology — -when the conversation ceased expanding…

Rabbi Rappaport has addressed this issue, and he says, “Let’s put the Halachah aside for a minute and talk about these human beings.” There are laws between people and G-d and those are up to the individual, but there are many laws which apply between people and these are just as important. Treating people kindly, that’s important. The noted Torah scholar, Rabbi Akiva, said that the most important thing in the whole Torah is to love your neighbour as yourself. All the rest is commentary.

Tova Benjamin is a poet & student & staff writer for Rookie Magazine. She sometimes tweets @drosophilala.

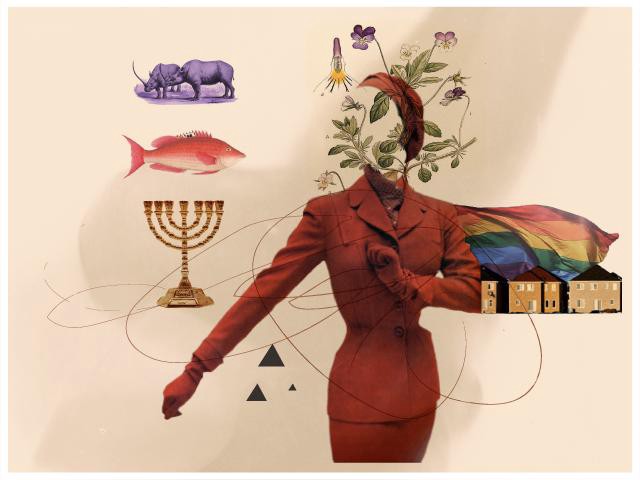

Maegan Fidelino is a graphic designer living and working in Toronto.