Communing With Carson

by MonikaZaleska

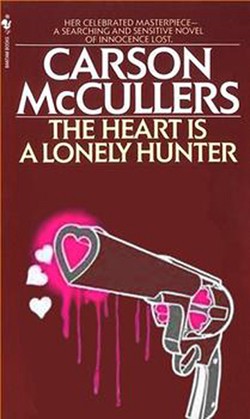

Carson McCullers found me during my loneliest year. An ingénue-writer, at twenty-three she blew New York away with The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, her story about a little Southern town, a girl named Mick, and a deaf man named John Singer. Literary fame followed, then divorce, illness, and early death. She had a series of strokes throughout her adult life that left her partially paralyzed; the last one led to her passing at age fifty. McCullers spent much of her adult life “in recovery” nursing a thermos of tea and sherry. It’s a story that indulges our favorite cliché about artists — that out of great pain comes great work.

At the time I felt I was suffering too: I was living in a small Polish town near Ukraine’s border last winter, teaching nine English classes a week, spending a lot of time on the Internet and the rest of it reading. I bought books whenever I could. I managed to find Mary McCarthy and Luce Irigaray secondhand, paid too much for Zadie Smith, Haruki Murakami, and Mario Llosa Varga in Kraków, and was sent Roberto Bolańo, Javier Marías, and Chris Kraus by mail. But Carson McCullers came to me. In Paris, her novella Ballad of the Sad Café poked out of a stack at the Canadian bookstore. In Amsterdam, Member of the Wedding seemed to call my name from across the shop. In a Berlin, her biography nearly knocked me on the head as it fell into my open arms. In my diary, I wrote:

Why do I have such a sudden, gasping appreciation for Carson? Is it because I am reading from the position of admirer? And am moved by her personal problems? All I know is that Mick is wonderful and I want more. I am in such a hungry reading mood I don’t know what to eat first.

I felt my attraction to her writing was somehow caught up in her personal tragedy and that was wrong, even though my relationship with all my favorite writers is tinged with this curiosity. I have always been a sort of detective, holding a magnifying glass to their work, excited when I noticed a detail of their lives enlarged in their fiction. I took my cues from their biographies, sewing a bonnet like Laura Ingalls Wilder at age eight, trying to drink like Hemingway at sixteen. Eventually, academically, I learned to correct myself: the author — sorry, the narrator says, but that divide seemed false to me, as if the narrator could ever exist without the author behind them.

But this uneasinesss was why I held off on reading McCullers’ biography nearly all year. The 600-page tome by Virginia Spencer Carr, titled The Lonely Hunter, became my desk in bed, Carson staring back at me from the cover wearing a man’s suit, her hair short and blunt like a kid’s. A study in contradictions. She looked like the kind of girl I have always admired: no-nonsense but spunky, unafraid to get her clothes dirty or say the wrong thing. I, on the other hand, was self-conscious, self-critical, and careful to a fault. Which is why I decided that diving right into her life story was the wrong move. Was I just looking for that twisted pleasure we get out of knowing the minute details of other peoples’ tragedies? Even in my loneliness, I knew this wasn’t the part of her I wanted to connect with.

So I read her fiction. I read of Southern towns where adolescent girls roam barefoot until frustrated, they lash out — a knife thrown at the kitchen door in Member of the Wedding. I read of looking out New York windows into other peoples’ apartments, of failed loves, and of the despair of being held apart because of race, class, or disability. No one writes about loners like Carson. Strange, the intuition with which she wrote damaged characters years before becoming the wounded artist at work.

I used to pine for the expansive adventures of Steinbeck and Kerouac, idealizing the ruggedness of those writers, their absolute freedom. Carson’s work, infused with her tomboy spirit, appealed to that naïve part of me that couldn’t see the role of gender in shaping those narratives. But Carson’s work I didn’t have to idealize. Her characters weren’t American heroes in that grand and masculine sense, but instead, overlooked warriors of the heart. These narratives, especially of young women, opened themselves to me as a different kind of freedom. In them, I saw stories that I could take part in, and the kind of writing that I could adopt as my own. It’s fitting then, that my travels around Poland were less intrepid than introspective: ceaseless wheat fields unfolding outside the bus window, waiting on train platforms, arriving at odd hours:

Whole days spent alone. Journaling. The creativity of boredom. What comes out when you have nothing else to do.

It was during the last leg of my travels that I finally read Carr’s biography of McCullers’ life. I lugged it from the Baltic Sea to the Czech border. It was soothing to learn about those spans of time when a prolific writer like McCullers didn’t pen a word (felt relief), or to learn about the tenacious discipline with which she worked (felt resolved to push forward, write more, better). I read about her doubts in letters to friends, and her arrogance. “I have more to say than Hemingway, and God knows, I say it better than Faulkner,” she once said, dismissing those literary demigods. Carr writes that Carson could be harsh, obsessive, and even cruel, but she gives equal page time to her tenacity, character, and sheer ego.

“To Carson…” writes Carr in that heavy volume that spans McCullers’ hometown of Columbus, Georgia, her early days in New York (reading in the telephone booths at Macy’s), France, Ireland, and all her days of illness and depression, “reciprocity in a love relationship seemed impossible. One could never be both lover and beloved at the same time.” Is there any truer, deeper feeling, as a teen, than that of unrequited love? Carson carried that malaise of being a young woman throughout her whole life. In “Stone is Not Stone,” one of her early poems, she says, “There was a time when stone was stone/And a face in the street was a finished face,” as if there ever was a time when everything was comprehensible. That idealism never left her.

In both her ego and her idealism I found a new kind of hero. I cut my hair short like her and tried to take up chain-smoking. Old habits die hard. I had held the magnifying glass up to her life, but it wasn’t learning the facts that had helped me. It was encountering her work at just the right moment, when I needed a new model for what to strive for as a writer, not so much adventure as boldness of spirit, not so much virility as vulnerability.

Now back in the U.S., I can see that my sadness drew me to the tragedy in Carson’s life. But my small unhappiness was really nothing like Carson’s illnesses. After all, I met many friends in that small town who would have taken me out for a beer if I had just knocked on their door. Instead I wallowed in my reading and projected my unhappiness onto Carson and her work. I found what I was looking for, but I also see a kind of foolishness in my pursuit. I go on reading about what writers ate and when they slept and who they slept with as if these trivialities could add up to the sum of their work, and give me a formula by which to create my own.

Despite this, I recently dragged my friend Hanna to Brooklyn Heights. I wanted to find

The 7 Middagh Street house Carson lived in right after publishing The Lonely Hunter. I looked up directions at the office and we set off along Brooklyn Bridge Park. As we walked I felt that same push and pull that had made me set aside Carr’s biography, the futility of expecting a book or a place to be invested with the artist’s spirit, and yet the draw of capturing a bit of hero’s strength.

In this case, the decision was made for me. We were standing on the marked spot, looking at our phones, when we realized there was no such house. It had been razed decades earlier to make room for the BQE.

It was silly of me to think she would go on existing there, in stone or in spirit, just because I had enfolded her narrative into my own. No, Carson was up in whatever heaven or hell is reserved for writers, drinking tumblers full and giving our patriarchs shit.

Monika Zaleska is a staff writer for Rookie and a recent contributor to Filmme Fatales. Follow her sporadic thoughts here and read about what she’s up to here.