An Archive of Longings

by Kiva Reardon

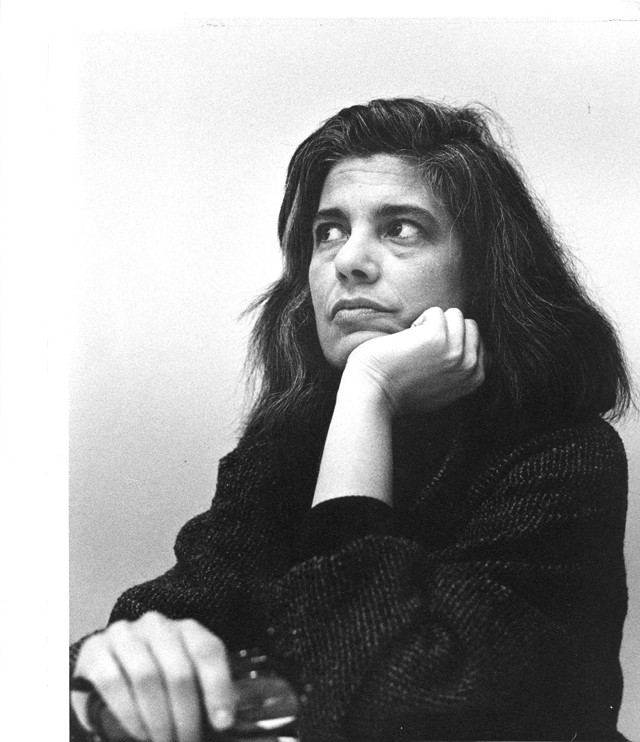

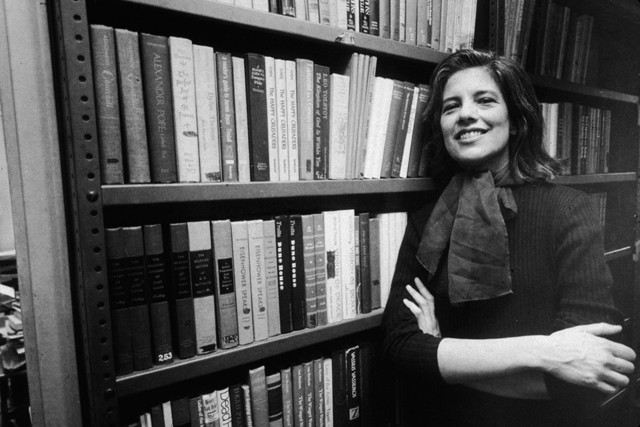

December 28th will mark the ten-year anniversary of the passing of Susan Sontag, one of the greatest intellectual figures of the 20th century. Known for her acerbic wit as much as her silver-streaked hair, Sontag intentionally crafted an iconic public persona of a steely yet sexy woman (watch her eye-fuck Andy Warhol’s camera, legs akimbo, in 1964’s Screen Test) who was not to be taken lightly (witness her publicly eviscerate Norman Mailer for the use of the pejorative term “lady critic” during a 1971 Town Hall on Women’s Liberation). But while Sontag lived publicly as an intellectual — lending her name to the Anti Vietnam War Movement, speaking out against the Bosnian War and challenging American imperialist reactions to 9/11 — her private life remained intentionally, well, private, especially when it came to her sexual orientation.

For filmmaker Nancy Kates, this was a paradox she hoped to unravel in Regarding Susan Sontag. Using interviews with Sontag’s family and ex-girlfriends, archival newsreel footage, and casting Patricia Clarkson to give voice to Sontag’s private journals, the doc is a far sexier (though still serious) take on Sontag than might be expected. Speaking over the phone from a dog park in her native San Francisco, Kates discussed her own relationship to Sontag’s work, the dead’s right to privacy, and if there’s really such a thing as having “too many girlfriends.”

When did you first encounter Susan Sontag’s writings?

I don’t have a distinct first memory of reading her; I just know I got interested in her as a sophomore in college. That was right around the time A Susan Sontag Reader came out; I started college in the fall of 1980 and that book came out in 1982–3. I still have my copy of A Susan Sontag Reader, but during the process of making this film it split in two. It was this big, fat paperback and it just split. There’s something funny about the fact that I’ve had this book for more than half my life and it’s only now starting to disintegrate. When I was younger, I used to dip into it occasionally, and I didn’t really know that much about Sontag. When I started making the film I thought I did, but then I started doing a lot of research.

Can you talk more about the research? In the case of this documentary, there’s not only the work involved in understanding Sontag’s writing, but also an incredible amount of visual research, as you incorporate a lot of newsreel and film footage.

I did work with archival researchers to find a lot of the visuals. It was a huge effort with a large team of people working on that element for a long time. In terms of the print research, I did the majority of that. One thing I realized is that Sontag can be hard to read, so I formed a Sontag reading group that met every month or two for a couple of years. That was fascinating because it was so much easier to read her if you then had the opportunity to talk with other people after. Although, there was one meeting where we had read The Benefactor [Sontag’s first novel from 1963] and Death Kit [her second novel published in 1967], and several people threatened to resign. In fact, I think one person did resign as a result of that meeting because they couldn’t stand those novels. In any case, this reading group is mentioned in the credits of the film, but I don’t talk about it a lot in interviews, even though the group was instrumental in the making of the film. I also spent a lot of time at the archives at UCLA where her papers are. I’m kind of a ferret, so I just dug deep into all her work and films, and, to a certain extent, what had been written about her.

When did you first decide to make a film about Sontag?

I was deeply saddened by her death, which is what prompted me to initially make a film about her, but I didn’t start working on it until 2006. I had no idea it would take this long — it was an eight-year project. When it was finished, HBO suggested we should broadcast it in November, but I said it should be December given it is the anniversary of her death. While making the film I was intensely aware of time passing, and it felt very ominous, like I better hurry up because someone else was going to make a film about her.

Because a fair amount of time passed as you were working on the film, did your intention behind it change? Or do you think popular views of Sontag did?

I think for perceptions to really change even more time has to pass. I knew it would have been a different film if it had been made before she died, or started before she had died. For me, it was an act of memory and keeping her story in consciousness, but it wasn’t intentionally supposed to be commemorative.

Can you talk about casting Patricia Clarkson to read Sontag’s journals?

On a practical level, I knew we needed someone to read them because Sontag didn’t record them. And even when there were instances of her having recorded her readings, they didn’t always include the lines we needed, so to speak. So we knew early on we needed an actress. At one point I considered Vanessa Redgrave because she has such a distinctive voice. That didn’t work, so I kept looking for an actress who was classy, gracious and intelligent. Clarkson then ended up being my first choice and it was amazing to work with her.

Clarkson brings a lot of sexiness to the readings too.

When we were recording, especially the parts from the earlier years of Sontag’s life, I asked Clarkson if she wouldn’t mind being less sexy, which is the most ridiculous thing you can say to an actress, right? “Please tone it down!”

But that sexiness is important, as we don’t know a lot about Sontag’s personal life, especially her lovers, and this plays a big role in this film. What was your approach in balancing Sontag’s public intellectual life with her personal one?

That ended up being the central tension of the film because she was so much less certain of things in her private life. She had such a fierce public persona, but on the inside she was just as confused as the rest of us. She certainly knew she was sexy, but she didn’t have that same kind of self-confidence in her relationships as she did in her writing. That was what I found to be the most interesting thing about her: she had succeeded in creating this persona, but that persona may have prevented her from being super connected to people. Also, because she was gay, I felt we should explore her personal relationships. I wasn’t able to talk with any of the men she was involved with — most of them aren’t alive and there weren’t that many of them — but I did dig up a bunch of ex-girlfriends. Because of that, I think the film ends up feeling more lesbian than she was. Though, I think that Sontag wanted to be known for who she was at some level. Alice Kaplan, who we interview in the film, said she wouldn’t have sold her journals that contain so many facts about her relationships to UCLA unless she wanted to be known for who she was. Sontag’s sister [who’s also interviewed in the film] disagrees with that, but there’s nothing any of us can do but speculate about what Sontag would want after she’s gone.

After watching the film, I mentioned the interviews with the ex-girlfriends to someone and they didn’t even know Sontag was gay.

I didn’t know until shortly before she died. She would also object to the word “gay” in this context — she didn’t like to be put in a box; she didn’t want to be labeled. It wasn’t that she didn’t want to be seen as a lesbian, she didn’t want to be seen as a woman in many ways. She wanted to be attractive and did use her good looks to get attention, but she almost wanted to be this un-gendered brain. I think that she really believed that if she were seen as a lesbian, she would be dismissed.

It seems notable that she never claimed a gay identity. This point comes across as something that’s lamented by a few of her exes in the film.

And even her fans. By the 1980s and 90s, people wanted her to come out because she would have been a really powerful icon. And she refused. It’s something that she remained stuck in the past over, because I don’t think she would have been punished for it in the 1990s the way she would have been in, say, 1959. I struggle with her closet a bit, and I noted that every person I interviewed defended her right to be in the closet. (Terry Castle being the exception.) But even with those defenses, the overall tone was, “Oh get over yourself, who gives a shit.” Then there was the argument that she didn’t have to come out, as there were all these indications in her work that she was gay, including her first novel, that were just coded.

Did you ever worry about outing her?

I had a lot of conversations over the course of making this film about whether the deceased have the right to privacy or not. I decided early that they don’t, or at least they don’t have the same rights as a living person does. Maybe that’s an obnoxious position to take, but I also thought about those journals sold to UCLA, and her son publishing some, and felt that I wasn’t doing the outing. I might have been echoing it or reverberating it. There have been a few people who said there are too many ex-girlfriends in the movie. That’s a hard one for me, because what’s the notion of “too many girlfriends?” Sontag didn’t have a single monogamous relationship like some people do. Each of [her] relationships were extremely important to her, but they didn’t last that long. Why condemn her for that? It becomes this problem of gay biography — how much do you tell and what details do you go into? I wanted this film to be taken seriously, but I felt [that] talking about her sexual past was important to telling the truth. Period.

Regarding Susan Sontag premieres December 8, 2014 on HBO.

Kiva Reardon is the founding editor of cléo, a journal of film and feminism. She writes about and watches a lot of movies. For proof of this, please see: @kiva_jane

Image credits, in order of appearance:

1. Andy Ross/Courtesy of HBO Documentary Films

2. Dominique Nabokov/Courtesy of HBO Documentary Films

3. New York Times Co./Archive Photos/Getty/Courtesy of HBO Documentary Films