The Best Time I Dropped Out Of College (Twice)

by Sarah Nicole Prickett

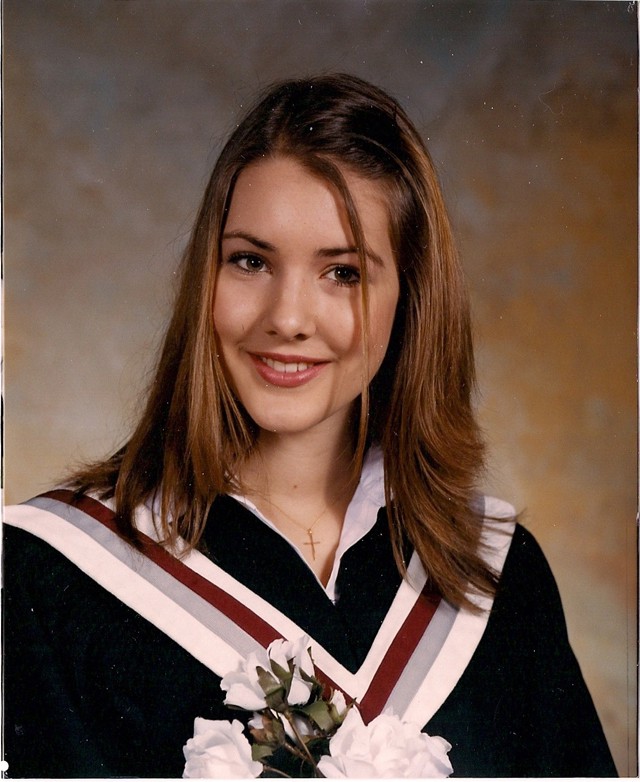

I dropped out of college the first time in a bright kind of fall. The college, because I’m Canadian, was actually called university, and the university was of Western Ontario, a great, big, unevenly beautiful school at which both of my parents had matriculated. It would have been nice if that’s why I too had enrolled, or why my decision was forcibly encouraged; the real reason was that the U. of W.O. was a 12-minute drive from our house, where as a stay-at-home student I’d cost a lot less, help with the chores, and continue to attend our evangelical hell-hole of a church.

Resigned, I spent my first year of an undeclared major wearing comfortable shoes and riding the city bus to school. I remember making very few friends. One of them I kissed for 20 minutes by the light of a neon Sublime poster, and when my mother read my diary to find this out, she not only sat me down for a long talk with my dad, but also, the following Wednesday, showed up at 3:10 p.m. to an even longer lecture on Hegel. Five hundred students of Modern European History turned to look at her. I looked for a sharpened pencil. She just had a feeling, she said to me later in the van, that I was doing something here besides learning.

For once, my mother was like other mothers: she was right. Instead of studying anxiously into the night, I lived in wanderance of the half-lit campus, loitering in the computer lab, cold on the long stone steps, my head a cloud of songs for invisible girls. Sunny Day Real Estate, Brand New, The Gloria Record. You’re just like everybody else / There’s no one like you. Jimmy Eat World. Saves The Day. Even Dashboard Confessional, until I found out about Bright Eyes. Now I know a disease that the doctors can’t treat. I missed my high school best friend and both my sisters; the only other girls I really knew, I knew by reading their blogs when blogs were anonymous. In the spring I started dating my second-best friend, a boy named David whose patience under parental exigencies — no visits after dark, no time alone — suggested a sureness of me that I lacked. I wanted to sleep with him badly.

For my second year at Western, I took $5,000 from the joint savings account I held with my parents and rented a basement apartment near school. I did this without telling my dad, who was on a missions trip in Peru, or my boyfriend, who was on a drinking trip in Barcelona. Sensible omissions, both: I was terrified to disappoint my dad, and I didn’t want David to worry about me. And there was something else telling in the lie by silence, in not-telling only the two men. I was trying to be unlike my mother, a favorite of her father’s who frequently referred to mine as “the man of the house.” At the time I thought the man I was rebelling against was God.

The first six months were heaven. I loved sex. I loved Jägermeister. I gained 10 to 15 pounds on birth control and processed cheese slices; I had never been happier. I liked my roommates, three quarters of whom were kind to me after I ran out of money and charms and spent days and weeks of April refusing the light. It was definitely April, or it was March. How it all got so bad is a blur. I blocked the door. I blacked out the basement windows. I remember myself curled in feral positions, sounds on repeat getting louder, climbing up and out of the window to piss in the grass. When I had an exam, I studied for sixteen hours, then didn’t go. I called home and my parents said they would rather I didn’t talk to my siblings.

Summer improved me: I got a job and forgot I’d failed two of my classes, or three, and anyway I was drinking a lot. Something happened at a party, like it does; I wrote about it once. No way I’d talk about it then. By the end of August, David’s mom and David’s mom’s psychiatrist were telling me to go on Paxil, and I listened because of the way I saw she loved him. If I obeyed her commandments, the Bible told me it was because I loved her; if I loved her, she’d love me too. Three weeks later I was alone in David’s parents’ house when the only thing I could find to alleviate the all-sides effects of either the Paxil or its failure was a half-full, plus-size bottle of extra-strength Tylenol. The doctor said I took enough to kill me. I said I’d had a very bad headache. Even now I refuse to believe it was myself I had wanted to kill, if only because I made no other decisions that year. When, after a few weeks of classes in that bright fall of 2006, I left without having paid or unenrolled, it was not because I was brave or had anything better to do, but because I had left myself no way to stay.

I dropped out the second time for some of the old same reasons, but also because my meanest, favorite teacher told me I’d be alright. The university was Ryerson, and in particular the Ryerson School of Journalism in Toronto, Ontario, where I spent almost two years unlearning how to write so that I could type for a living.

At the end of the second semester, we were asked to write a national magazine-style story on a timely subject; I chose to interrogate the undergraduate degree and its rapidly declining value in a recessionary age. To this masterwork of dispassionate aggression, I attached a personal coda that all but announced my own departure from the (allegedly) selective program that had accepted me despite a) my academic record and b) the fact that my application contained a discursive meditation on the death of Hunter S. Thompson, approximately two of whose essays I had read. Writing this now, I feel uselessly sorry to whomever might have taken my seat at “Rye High.” I wonder if someone told her, when she didn’t get in, what nobody ever told me: no matter how much time or money or energy or innocence it costs you, school doesn’t automatically prove anything except that you paid.

It is because I couldn’t afford not to work — because necessity is destiny, in the end — that I was alright. With a degree at 22, I would have been the serious young woman. With a degree and a savings account at 22, I would have been the serious young woman novelist. With a trust fund, I would have been the bride, 22, dead after “falling” into the Niagara, but with none of the above and nothing to complain about either, I was the clever girl. I made myself the “assistant culture editor” (synonym: intern) to a boss at a glossy who called me “Becky Sharp” and who showed me how to write to a dollar count. I moved in with my boyfriend, who had a salary. These anoetic decisions were my first two fiscally cool moves. I could never make anything last.

It is because of an ease that the teachers couldn’t teach that I wrote quickly and unsparingly and too, too much in “a voice” that got attention, not care, because a white hot feminine voice is good for both ratios and traffic, is the first voice you hear at a party and the easiest to mock when you walk away, is easier still to fry, the first sound of burnout. “A voice” like this is recognizable but not to itself, which is to say that half the things I wrote at 21, before I would unspool myself for cash, are better than most of the things I published when I was 22 to 25.

But now I’m just making excuses, and it was me who should have taken some care. I was good at trying. I was not good at trying again. In Toronto, a rapid achievement of stasis counts as victory, and on a clear day I felt like a student who’d stayed for a “victory lap,” a fifth year that isn’t borne of failure but of a faltering in progress, a faith going bad in the future. I knew I had to become invisible, to loiter and not belong. I moved to New York, of course.

The other day I emailed my favorite, not-so-mean teacher to ask how she remembers my leaving. Maybe it wasn’t that dramatic, or even altogether my doing. Cathy could have wanted to be rid of me. There is an age of difference between being “too good for school” and being “no good for school,” and I was so often the latter.

I was also a brat. My parents and their rods had paradoxically beaten into me a tendency to shrink from all rule, especially the kind of rule you might call “common sense.” Because I grew up in my head, I lacked a certain socialized edge in class competition: I couldn’t see the point in striving to do a little bit better than other people at more or less exactly the same tasks, or else I strove desperately to win in my own way and not any other. And, too, I easily confused a want of humility with confidence.

Cathy wrote back almost immediately.

“You were so bored and it was so obvious,” said Cathy, whose generosity of email I’m condensing. “Because of this, you were experimenting with all kinds of rad styles. It killed me to cross out a riff of yours over a stylistic device I deemed not “appropriate” (!). What a prissy word. It should be struck out of the lexicon. You were writing wild and free, which I so wanted you to do but couldn’t allow because of the bloody course constrictions.”

It is my second and third year in New York. I’m putting myself through school, is what it feels like. I think it’s not possible to live here. I think it’s not possible to be bored: ignore the last twenty years, the twelve-hour work days, the tourists, the cab fares, the bad Taylor Swift song, and look at the sun crash over the skyline, a triumph of matter over mind. So too are the pills I swallow at different times, because it was either lose my head or keep it locked up under a pharmaceutical sort of conservatorship, and look — it’s just not possible, without a cold elision of the panic and financial constrictions, to complete all the courses I’ve set. I forget if I was ever wild or free, or if I was feral. Or if freedom’s just a word for a bigger cage. It’s weird because I’m married, but I’m reprising the “time of my life,” making all my work homework in no routine, so little sleep, six empty Gatorades on the kitchen table in the oldest suburb of the biggest fucking mall in America. The grid is my cul-de-sac, the 7/11 is my home. I’m fifteen years old / And I feel it’s already too late to live / Don’t you?

Lately, since my persona’s a little more successful than I personally know how to be, younger people ask me whether they should drop out of post-secondary school, and if they do, will they be alright. I haven’t known how to define myself so that she or he can be satisfied and answer, “me too.” Now I’ll try.

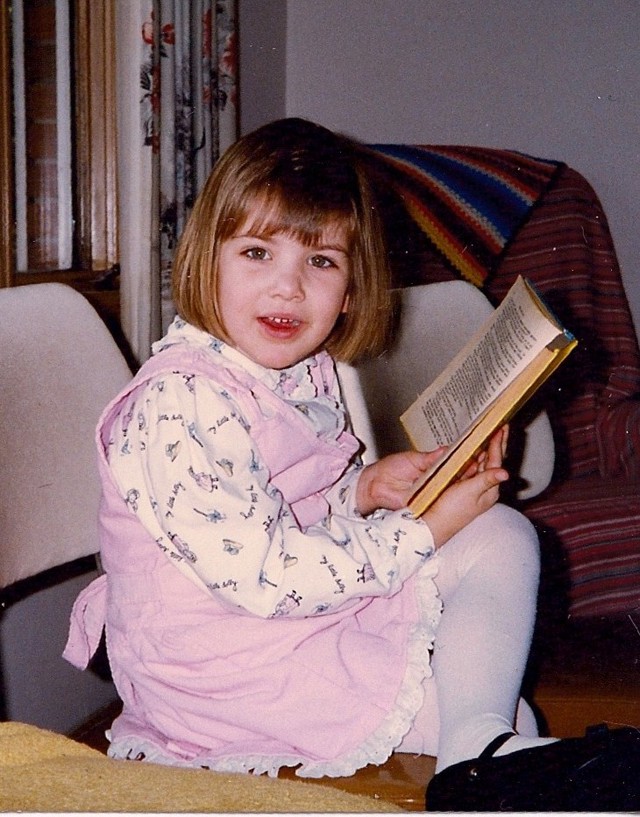

In senior kindergarten, I was an absolute champion napper. Not only did I eagerly partake in every scheduled naptime, but also, no lesson or activity was safe from my will to take my cloud-patterned blanket and nap instead. Such a restful child, the teacher said appreciatively. My mother tried her politest to nod and smile. In fact, then as now, I was one of the least restful members of civilization, and had staged all my napping as a silent protest against — well, against the bloody course constrictions, even then. I could read sentences and several books; Mrs. Johnson was teaching us letters. “Why do I have to be awake,” I said to my mother, “when I already know what’s going to happen?”

Many of my depressions, inextricable as they are from the times I have dropped out, cracked up, broken a promise, forgotten to do something, forgotten how to or why I should do anything, seem to me now to have been less like bouts of disease and more like attenuated naps. Many began with déjà vu and/or a very bad headache. Often these warnings came during or after a schedule, a physical sickness, or even a landscape that made me feel sameness for a while. Eventually I got into a life with almost no habits and no flat horizons so that I would stay awake longer, and even now, I could only finish this essay because — clearly — I had no idea how it might end.

Sarah Nicole Prickett is a writer in New York and the founding editor of ADULT.