Some Things I Cannot Unhear

by Durga Chew-Bose

1.

In 1968 James Baldwin was a guest on The Dick Cavett Show and said, “…as Malcolm X once put it: the most segregated hour in American life is high noon on Sunday.” High noon, he said in a slight baritone as if trying to find the right key for a song. Baldwin then goes on to give examples of other institutions, not just the Christian church, where systematic racism has wielded its power; the labor unions, the real estate lobby, the board of education. Part of this episode can be found on YouTube and runs a swift one minute, one second. Baldwin’s voice — -its’ near-sport of a voice — -is one I cannot unhear. The way he says “evidence” is capable of galvanizing the most blasé listener. His is a staccato that quickens in clip when Baldwin repeats words like “white” or “hate,” but ripples with words like “idealism” so as to wane its meaning into nothing more than what it is: a naiveté.

When Baldwin asks a question, it does not ferry the inflection. Instead, he issues it declaratively, testing the acoustics of a room. Close your eyes and sure, Baldwin has a sermonizing tone, but one that bounces like a boxer in his ring. Baldwin’s voice multitasks, and requires of me what he was asking of America and the world: to pay attention. His words toll and have carried their repercussive meaning into today. So much so that in August when the headlines read “No Fly Zone Over Ferguson,” for a minute, I only heard those words in Baldwin’s voice.

2.

My father has taught our 2-year-old Welsh Terrier, Willis, to “Play dead.” PLAY DEAD, I’ll hear him say when I’m home for a visit, sleeping in and playing dead myself, but still in earshot because at home, sounds, I’ve noticed, echo more. After all, home is a succession of sounds — keys sliding on a counter, groceries hoisted onto the kitchen island, oil splattering in the frying pan. So just like that, I’ll hear my father say, PLAY DEAD. Two words that I can I now never unhear. PLAY DEAD, two words that oppose but aren’t opposites. One is meant to be light: Play! The other is blunt. It moors.

When Willis hears PLAY DEAD, he lays flat on his side and possums into a jelled state. In those seconds, I’ve come to learn, Willis is the ultimate state of “dog.” Meaning, he is expectant. A treat is on his horizon. Sometimes Willis will side-eye my father, like “C’mon, man.” For those who don’t know, when a dog side-eyes you, the white of his eyes can deploy more attitude that the most teenaged of teenagers. And so, sometimes I’ll stand on our stairs and spy my father saying PLAY DEAD, and even when Willis only half-obliges, my father stills hands him a treat and lies down beside him. In those moments my father is the ultimate state of himself: father first and everything else second. And in those moments when the two of them are playing dead, I quietly climb back upstairs, because as time passes and as I spot my parents do young, lighthearted things, I’m overrun by some cruel and preoccupying sense that I’m watching the memory of them.

3.

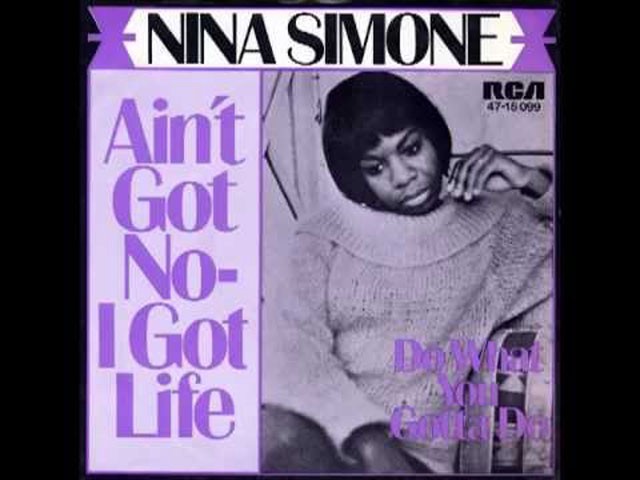

There’s a recording of Nina Simone’s “Ain’t Got No,” where Simone, after listing all the things she doesn’t have — a home, shoes, money, class, a country, schooling, children, sisters or brothers — she begins, around the two minute mark, to list all that she’s got, that “nobody,” she sings, “can take away.” Hair on her head, brains, ears, eyes, a nose, and her mouth. She has her smile, too. Her tongue, her chin, her neck, and, my favorite of all, her boobies. When Nina Simone shouts, “my boobies” in her syrupy, cool-shriek of a voice, it’s as if she’s invented a whole new body part. Boobies. These aren’t just breasts, they’re boobies; they bob and hang and sit like half-moons on her chest. They’re funny and beautiful. They’re boobies. And I can never unhear Nina Simone claiming hers.

4.

I was eighteen and hiking with my classmates in Mexico’s Copper Canyon when, while crossing a rope bridge, my foot broke through a rotten plank of wood and I plummeted thirty feet to the ground, landing on a dried-up riverbed of rocks. I don’t remember falling — that was quick like something that didn’t happen at all. I came to and I remember the sensation of my tongue touching my gums and the taste of blood, and mostly the pang of vanity — I’d lost some teeth, it was clear. I remember the faces of my classmates rushing towards me and holding my neck and asking if I could wiggle my toes. I remember thinking, “Lie. Even if you can’t wiggle your toes, just lie.” But I’m a terrible liar and I remember deliberating on that too. These were my thoughts as blood trickled down my cheeks and as I committed to memory the faces of people I knew, whose faces now were stricken with panic. Warped worried brows and young eyes suddenly wiser because holding back tears will age you. Lips quivered and smiles cracked as I lay there answering questions — -my name, the date, where I was — and as I learned by heart as if studying for an exam, the way John’s eyelids blinked slowly as if allowing himself a few extra seconds to look away from my busted face as he held my hand, or the way our guide spoke at a gentle metric like a robot with a heart.

The adrenaline that was pumping through me and masking my pain was also prompting my everyday discomforts to surface: I really did and still do hate being the center of attention. I’m no good at answering questions about myself even if they are basic and were meant to address any head trauma, like, “Durga, what did you eat for lunch?” I stumbled on the word sandwich and couldn’t remember if I’d eaten my apple or if it was still in my pack. Never before had I imagined that misremembering my lunch would yield such concern.

But what comes to mind most from that day is the sound that slipped from my mouth as my foot fell through the plank. It’s hardly a sound and mostly a breath. A gasp that was cut short, as if sliced by a butcher’s knife: it sounds something like, HUH. I can never unhear that sound. HUH. It’s the ghost of a sound. But on that day, it was the very human understanding that gravity was real and that I was about to fall and that nothing was going to catch me.

5.

I can never unhear Allen Iverson saying the word “practice.” On May 7th, 2002, after being eliminated by the Celtics in the first round of the Eastern Conference Championship, Allen Iverson, who was the previous year’s league MVP, gave a different kind of history-making performance: a press conference that lasted almost 30 minutes. For some NBA fans like myself, Iverson represents a precise time in the sport where the league — -small, 6 foot AI, played with a conceit that realized miracles on the court, like his rookie year crossover against none other than Michael Jordan. Iverson’s signature crossover was the kind of basketball that could make anyone a fan of the game — the sort of speedy sparring that, even now when you watch clips of him play, unfold as if there’s a spotlight following only him. There was no denying Allen Iverson and so, when his 2002 press conference, following the 76ers’ elimination from the playoffs and reports that he and coach Larry Brown were at odds with each other, aired, there was a sense that Iverson was working his on-court crossover, off court — choosing to spar with one reporter in particular who brought up the topic of Iverson’s absence from one or two practice sessions. “I’m supposed to be the franchise player,” he responded. “And we in here talking about practice? I mean listen, we’re talking about practice. Not a game! Not a game! We’re talking about practice. Not the game that I go out there and die for and play every game like it’s my last, not the game, we’re talking about practice, man. I mean, how silly is that? We’re talking about practice.”

Iverson says the sentence, “We’re talking about practice” no less than thirteen times as if sanding down its implication with each slackened delivery of the word practice, and more so, the credence this one reporter was giving it. Like watching Iverson freestyle with an opponent for a few seconds only to get low, fake right, and then make a quick crossover dribble to his left and lose a defender entirely, Iverson’s press conference dissidence was showy but earned. Lesser people might call it a rant: I for one, can never hear the word practice uttered by anyone without Iverson’s disenchanted tone hurtling to mind, because yes: What were they talking about? Practice?

6.

In the basement of the funeral home where family were soon to arrive, my mother, my aunt — my father’s older sister — and my stepmother, all gathered in a stark white room where my grandmother, Thama as I called her, was lying dead on a table wearing a white sweater blouse and petticoat. She looked smaller, as though she’d shrunk since I last saw her a couple days earlier in the hospital. I was worried her feet were cold. Of course they weren’t.

The morning of the funeral, my mother had asked me if I wanted to join her later as she dressed my grandmother in the sari my aunt had brought — deep forest green with a gold trim is how I remember it, but I might be wrong. It could have been navy. I was seventeen at the time and said yes the way seventeen-year-olds say yes. I said, “Sure.” Mostly, I was eager in my curiously selfish divorced child way to witness my mother and stepmother in the same room. I was worried they might fight — that someone would yell. Nothing could have prepared me though for how silent those next twenty or so minutes would be.

And so, I walked in behind them, shyly observed my dead grandmother and proceeded to stand just beyond the door’s threshold, attaching myself to the wall. There we were, five women, one dead.

My aunt unfolded the sari and from that moment on, all I heard was: nothing. Nobody spoke. I will never unhear that nothing. It was the loudest nothing I’ve ever experienced. Three women folding and tucking, and pleating the silk sari — forest green, yes, now I remember, it was a subterranean green, darkening where the sari gathered and glimmering where the gold embroidery caught the room’s awful fluorescent light. They lifted my grandmother and worked around her limp body with a delicate simpatico that was born right there and then; none of these women were particularly fond of each other, but they loved my Thama deeply. Circling her body, they were done quickly. I remember the word “efficient” popping into my head and balking: I was an incredibly clumsy mourner, it turns out. I remember my aunt placing her hand on her mother’s hand and briefly, death was, I wanted to cry out, the most incredulous invention.

I rarely think of that room or the five of us in it; or should I say four? But that silence, which I cannot unhear, occasionally dawns on me. Noiselessness, I’ve come to learn, is simply how some memories age.

Durga Chew-Bose is a writer living in Brooklyn.