Let Me Love You

by Fariha Roísín

A couple of months ago a very good friend of mine turned to me as if she had a deep secret. She premised the statement with shame. It was one of those non-verbal cues of uncomfortable realization that I inherently understood. Rendering her incapable of mouthing the full words for a few moments, blistering her sentences with falters and a fusillade of, “how do I?” and then, “okay, so — ” and then pausing, again, until finally, she said — “I don’t like it when people compliment you. I feel strange about myself when someone does.”

This friend and I have a good relationship. There’s no dancing around what bothers us. Hashing it out, rather than ignoring each other, we’ve agreed, is better. Striving to be paragons of female friendship, the aim of this relationship has been to strengthen each other, as a unit. We occasionally say things to each other that hurt; this was one of those times.

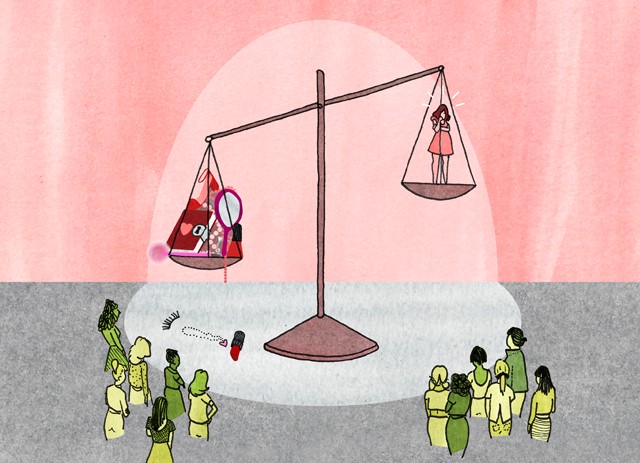

I wasn’t so much shocked as I was angered by what she said — which is hypocritical of me. I know the feeling of what she was trying to describe. I had felt it many times, too. It’s that feeling that only one girl in the room can be the “prettiest,” as in if I was inherently attractive, she; the other, juxtaposed against my beauty, suddenly wasn’t.

I had never understood why I have felt that way. I just knew that I did. I can remember a variety of stinging instances when someone complimented a woman before me and how I, always, immediately felt it was a ploy to criticize my own failures. That by virtue of this other woman writing a good piece of criticism; or this person having an amazing skirt; or shoes, or dress — I didn’t/couldn’t/hadn’t, I was a slob.

This is a social illness. At least it has been in the social climate that I’ve lived, and surrounded myself, in. We are casualties of the patriarchy, and by virtue of osmosis, I was taught to dismantle those around me, the women — vying only for male appreciation. We don’t question why we do it, we just do. It is a product of being socialized to feel as though constantly, we’re not enough. As women, mothers, daughters, wives — we’re constantly at war with ourselves. When I get angry with the woman complimented in front of me — how much of that does it say about me? How much do I value myself?

All the hottest girls at my high school all looked, dressed, and were the same; socio-economically, racially, or otherwise. We wore pink uniforms and baby blue socks. We would walk down to Cheltenham Station and linger there, waiting to go home, picking on girls in the interim — or otherwise be picked at. Anyone different is a threat if you’re not happy with yourself.

Since those days I have noticed a judgmental competitiveness within my friendships with women — why? Am I just bad with women? What if I’m the problem? This is emblematic of how I feel most of the time, with anything. Am I the reason he dumped me? Am I the reason they all hate me? Do they all hate me? How would I even know if they did? How often is it that when we ask: Is it me? Society screams back: YES! We aren’t even given a chance to absolve ourselves. When we discourage women their truths — whatever they may be — we discourage them of their complexities. We betray them.

Like a dull ache we hinge our lives on the bromides our mothers taught us.

I have never had this level of transparency with a girlfriend before. I’ve always had girlfriends, yes, but I was always striving to have something better, to be better. For me, the real life — very IRL — practice of “female relationships” has been a flawed experience that has forced me to question exactly what it is that I want from another woman. I’m constantly, actively, trying to figure out the social parameters to engage on a deeper level, and just be a good human, and friend.

I value a relationship where I can be open — not aggrandize each other’s failures to mutual friends, not having to look over your shoulders with cursory judgment. I value these relationships because they’re rare, at least for me.

After a few failed romantic relationships I realized I had constantly considered men to be my saviors. I had consistently betrayed myself, and my instincts, by sacrificing stronger relationships with my female friends and with myself, for some false dream. Harnessed by a desire to be saved, like a rom-com, I wanted my Mr. Big, and thought the best friends and me, in tow, would fall into place after I figured out my man, eventually.

Recently, it hit me — -I could be alone, romantically, forever. Emboldened by that thought, after years of abusing my emotions, I decided to focus on self-cultivation and female friends.

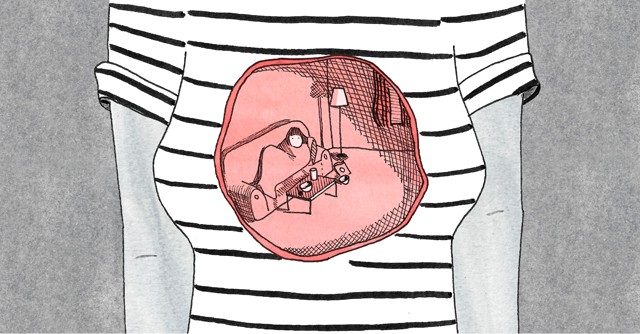

A couple of winters ago, I couldn’t walk out the door for a few weeks. I would watch episodes of Sherlock back to back, draw, write, eventually cry, and listen to Erik Satie. I was living alone in a big apartment that I couldn’t afford. Hungry, I would get dressed to go buy myself groceries and then dance at the door, sitting, then un-sitting, at the foot of my stairs. Like a seamless apparatus, I’d always turn back towards the warm confines of my self-hating doubt. I was terrified of being looked at. I couldn’t fathom the glaring trauma. I felt fat, I felt alone.

Society validates those questions in your head. Every magazine tells you how to look like her; how to lose weight; how you’re not better enough — and I believe it. And, then, each time somebody says something nice to a woman who isn’t me I immediately fall apart. Not knowing how to untangle myself, I can’t fathom telling myself that I’m okay, regardless of what he says, what she says.

One of my best friends from high school and I don’t talk anymore. It just happened one day. After years of being friends, I was angry with her for never writing to check up on how I was doing; later, I realized she could be thinking the exact same thing about me. Ego was the reason I never reached out. I was afraid of being vulnerable. I know it was my fault, at a certain point I couldn’t recognize her for the person she wanted to be — so I lashed out, my protectionism a stand in for all the things I couldn’t quite articulate. I was angry with her for changing.

I think I was in love with her. It still hurts when I think about it.

I have oscillated time and time again from my female friendships — defining and then redefining them. I sometimes puncture relationships like wounds, isolating friends if I feel they have betrayed me, uncomfortably searching for the friend that fits. Some of us, if not all, have been taught by grandmothers, aunts, society — that women are inherently “tricky” (the word my mother uses in lieu of “bitchy”) as if to insinuate that women are just, you know, bitches. We should get used to their betrayal. Like a real life mythology, we govern our lives with these precepts.

I have an interior Rolodex of all the inane things some of my female friends have told me about another friend, prefacing their experiences as if they were social assessments. Their purported quantitative data unfurl their absolution.

They believe in their truths, and at some point so do we.

We start treating a certain friend differently, or another friend with disregard, because that’s the fucked up loyalty we’ve decided on. And, so, this is going to sound like a cop-out, but I don’t like being mean to other women. The meanness that I have exuded, at times, wasn’t out of my own volition. It always stemmed from my inability to communicate my frustrations. In fear, I stayed quiet and then I festered.

We’re all mean until we’re not. Until we hear something about ourselves and then we have to pause — -angered by the audacity that people we don’t know are immediately dismissing us, or spreading rumors with neglect to our feelings. My meanness has always been a reaction to what I’ve heard another person say about me, but never to me — or; it’s a callow desire to be taken seriously, to exert myself — my vexations lie with being taken for granted. In the past I have equated meanness with power. Power is aggressive.

I obsess over all the women that hate me, making stories in my head about why. The reasons I have stored always mimic my own self-loathing, as if their hatred is expected because I am such a piece of shit in the first place. Residing in oneself is sometimes a lonely place.

There’s one female friend that I know trolls me on the internet; another who apparently (according to another friend) doesn’t like me even though she always says hey. It always hurts when you like someone but they tell everyone that you’re a crazy bitch behind your back. It reminds you that not everyone will give you the benefit of the doubt. It hurts because all in all, I just want to be embraced, especially by women. There, I said it.

Being a woman is a liminal process. There’s such a drought of diversity, knowledge, and complexity of our interior lives. It’s like we’re all adolescents again, or rather still — figuring out how to be people in a post-puberty world. I don’t really know how to love myself, so how can I learn to love another woman without raising a finger every time I disagree with her life choices, or side-eye her every time she says something ridiculous.

Here’s an insanely revolutionary act: why not counter each ill thought that comes through your head with an acceptance — -the acceptance that you’re not always going to agree with everything every woman does. Or an acceptance that some women will be tricky and some will be actual bitches, some of them will read Lean In and be the next Sheryl Sandberg, some women will call Beyoncé an anti-feminist, some will be walking contradictions, or some women will say that I’m a fake behind my back, or that I’m a liar, and that I don’t write well, or whatever — and just to accept that people are just people, women are just women, instead of reacting poorly and slamming them in whatever juvenile way that you see fit.

All of the hate stems from a disillusioned society that places men on top for being alive, and women are the ones that have to struggle to be constantly validated in the workplace, by their friends, peers, boyfriends, parents, shrinks. No wonder we can’t give each other a break, we’re terrified of not getting one ourselves so we snatch what we can from whomever we can. Dog eat dog. Bitches eat bitches. Except, no. Except what if we just didn’t do that anymore? I want to feed myself a new rhetoric now:

I am here for other women.

I am here for other women.

Can that be my new mantra?

Isn’t true feminism the love of oneself, amidst your body that isn’t always right — the thighs that grease together during warm summer heat; the brain that forgets words so idly — but isn’t it also an acknowledgment that we, as women, are all complicated human beings that flaw, and fault, and hurt, and aren’t the same. We contain multitudes. That, yes, we all shit and bleed — we will all die one day, but that we are as complicated, and as layered as men, and that no matter what, we are all worthy of chances — especially from each other.

I decided that instead of being angry when my friend said, “I don’t like it when people compliment you,” I would just look her in the eye, and say, with conviction, “I understand.” And to know, that deep in my heart, I sincerely meant it.

Fariha Roísín is a writer extraordinaire. Follow her rambunctious tweeting @fariharoisin.

Allison Burda and Cam Gee live and work together in Toronto. They post drawings of chubby dogs and other stuff at allisonandcam.tumblr.com.