The Erotic Thrill of Michael Douglas

by SorayaRoberts

Crossed, uncrossed. Crossed, uncrossed. Michael Douglas sat on stage at the Toronto Film Festival mirroring the most famous scene in one of his most famous movies. In Basic Instinct, Sharon Stone crosses and uncrosses her legs while being interrogated by a room full of men. At a dinner in his honor earlier this month, Douglas did the same thing while being interrogated by Tina Brown. And even though he was wearing pants (and presumably underwear), all I could think of was what was inside them; because to me, to this day, where Michael Douglas goes, sex follows.

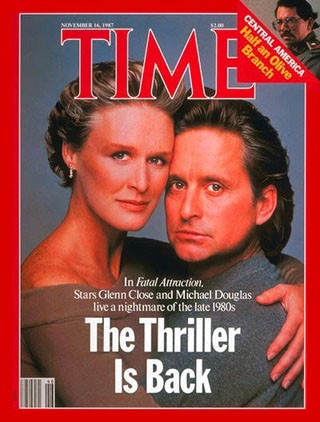

Between 1987 and 1994, Douglas appeared in what Brown referred to on stage as his “steamy trifecta,” Fatal Attraction, Basic Instinct and Disclosure. All three erotic thrillers could be boiled down to the same basic plot — a hapless hero is victimized by a sexually aggressive siren in a power suit–with Douglas trading in his Romancing the Stone swashbuckler for a fallible family man.

The role not only suited him better, it thrust his femme fatales, Glenn Close, Sharon Stone and Demi Moore, to the fore. And all three stepped up to slay the box office, earning, respectively, $156 million domestic in 1987, $117 million in 1992, and $83 million in 1994.

Fatal Attraction was not the first of its genre, but Adrian Lyne’s film about a happily married man who has a one-night stand with a single career woman became the ur-text for the mainstream erotic thriller. “Retrospectively, it can be seen as the perfect erotic thriller blueprint, hinging on sexual obsession and ending in murder,” wrote Linda Ruth Williams in The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema. It was the first in its genre to reach the top 10 at the box office, coming only second to Three Men and a Baby. Fatal Attraction was the movie to see in 1987, the latter day water-cooler flick that popped up everywhere from therapy sessions to the cover of Time. And though its audience grew by word of mouth, its success gave Basic Instinct a leg up five years later.

In the nineties, according to Williams, “erotic thrillers were the most discussed films and amongst the highest earners.” As the star of the genre’s financial climax, Michael Douglas was its main man. He proved that not only could he sell a film, he could sell a film in which the hero errs in the first half hour. For his trouble, Douglas was given a pay rise of about $10 million (according to his biography by Marc Eliot) for his second erotic thriller, Basic Instinct. The 1992 film also earned screenwriter Joe Eszterhas $3 million, making it the most expensive script ever sold. And it delivered –like Fatal Attraction, Basic Instinct was one of the rare erotic thrillers to land in the box office’s top ten (it reached number nine). Though Douglas’ “sex trilogy,” as he calls it, slipped to number fourteen with Disclosure, he was the archetypal nineties everyman castrated by girl power.

Feminism had spent three decades moving from the polls to the workplace; by the time Fatal Attraction set its bunny to boil, women like Alex Forrest were starting to fracture the glass ceiling. Writer James Dearden, who recently launched a stage version of his thriller, told The Atlantic in April that he conceived Alex as “a tragic figure, worn down by a series of disappointments in love and the sheer brutality of living in New York as a single woman in a demanding career.” Though she initially singed some bras, Alex eventually provided the rallying cry for ’90s Riot grrrls. “I will not be ignored,” she and third-wave feminists declared in the face of oppression.

As a sexually empowered bi femme fatale, Basic Instinct’s Catherine Trammel appeared to answer their call. Though gay activists protested what they saw as Hollywood’s demonization of two marginalized groups — bisexuals and women — feminists such as Camille Paglia praised the film’s progressive sexual politics. “What we’re flashing here is the center of life as it was understood in pagan goddess cults,” she says on the film’s DVD track of the pelvic-exam-cum-interrogation scene. “The mere sight of the female sex organ seems to destroy the men.” Thanks to controversies surrounding its sexuality, salaries and rating, Basic Instinct became the first erotic thriller to enjoy an orgasmic opening (ew).

Disclosure couldn’t quite measure up. Michael Crichton’s prehistory lesson featured Demi Moore as Meredith Johnson, a Trammel knock-off with a taste for red wine and rape. Released right as the Spice Girls were co-opting girl power, it was Crichton’s response to “feminism, sexual harassment, and the changing corporate world,” according to a profile in The Philadelphia Inquirer. The film came across as a ham-fisted polemic against double standards and, despite a lucrative run, it faded to black along with the golden age of the erotic thriller.

That’s right around the time I first saw Fatal Attraction. To this day it remains my favorite erotic thriller and the reason I can’t see Douglas without seeing sex. Unlike Basic Instinct or Disclosure, which veer into convoluted territory, its plot is simple–married man sleeps with woman; woman goes nuts–which allows its characters to be complicated. Douglas’ low-key performance provides the axis around which his lover, his family and his surroundings radiate. By playing Dan Gallagher as an everyman, Douglas acts as the viewer’s conduit into the upper-middle-class domesticity of 1980s New York and that which threatens it. With a little mood lighting and a lot of rain, who wouldn’t want a stroll through NYC’s pre-gentrified meatpacking district? Even with Alex Forrest by your side?

By comparison, Douglas’ other two erotic thrillers are a lot less thrilling. Basic Instinct’s Catherine Trammel, though she lives in a swanky glass box by the sea, is a little too smug, Douglas’ Nick Curran a little too pathetic, the plot a little too confusing, the script a little too bad. Disclosure suffers similar flaws, so it’s surprising that hero Tom Sanders still emerges as a lovable dad. He’s fallible, but he’s family.

It’s been twenty years since Douglas appeared in his last erotic thriller, but the dust from his frantic freight elevator fuck in Fatal Attraction still sits on his shoulders. I first saw him in person when he stepped out of the elevator and onto the sixth floor of Toronto’s Four Seasons Hotel for the Tina Brown dinner. At the very à propos age of 69, I saw Douglas stand and speak with two finance men (the event was sponsored by Credit Suisse) — all three of them in equally tailored suits — a man’s man. With slicked back white hair and a salt-and-pepper goatee, there was something unctuous about Douglas, as though he were playing a naughty Colonel Sanders.

Six feet away from him, I held a pulled pork slider in my hand, my cleavage exposed. There was cleavage everywhere, all facing Douglas, like sunflowers facing the sun. At one point he glanced at us in that slow casual Douglas way and then turned back to his conversation. That’s when I turned away. There were five decades of women before me who had shown him attention — I didn’t fancy being another. Which is not to say I wanted to sleep with Douglas (he’s older than my MOTHER), but I did want to sleep inside his erotic thrillers. This was the closest I would get.

Within the corporate clique, Douglas, thinner than he used to be, cut a paradoxical figure: intense and laid back, commanding and fragile. “That Douglas’s alignment of masculinity with deficiency predominates in the cultural image of the star over figures of sovereign power embodied by roles such as Gordon Gekko in Wall Street, and what Douglas has called ‘Prince-of-Darkness characters in A Perfect Murder and The Game,’ is testament to the power of the roles he took on in sex thrillers rather than other genre films,” wrote Williams. Much of this power came down to timing, specifically the moment men were losing control. “In a climate in which a crisis of masculinity is presented as a widespread cultural, economic and social problem, New Hollywood cinema needed a figure like Michael Douglas,” Williams explained.

He proved that men could be the weaker sex and still be heroic while the rest of Hollywood was still flexing its muscles. This was the era of the jacked-up action movie star: Tom Cruise playing with the boys in Top Gun, Bruce Willis Yippee-Ki-Yaying his way through the Die Hard franchise, Mel Gibson foreshadowing his future anger management issues in Lethal Weapon. Even the sensitive stars — Patrick Swayze in Ghost, Kevin Costner in Dances with Wolves — were infallible. And they were as perfect off screen as on. All of these actors were in ostensibly stable relationships. These were not guys who would cheat on their wives. Douglas was.

Before Fatal Attraction, he had reinvented himself as a muscular adventurer in 1984’s Romancing the Stone, but he couldn’t match his picture-perfect peers, neither at the box office nor in his personal life. He had acquired a reputation for womanizing off screen, according to the Eliot biography, out-partying even Jack Nicholson after One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest dominated the Oscars in 1975. “I was single at the time and I was determined to savor the experience in the most decadent of ways,” he said. Though he married Diandra Luker, a diplomat’s daughter, in 1977, his interest in Fatal Attraction a decade later suggested he felt pressured by the traditional family dynamic. “For me, the appeal is this very powerful, visceral instinct for obsessive lust amid seeming decency and normality,” he said.

Hollywood has its good husbands and its bad husbands — Douglas was both. His particular ability to juggle the two competing identities — home maker and home wrecker — was the reason Fatal Attraction succeeded when so many believed it wouldn’t. As film critic David Thomson wrote in The New Biographical Dictionary of Film: “[T]he trap of the movie worked because Douglas could commit adultery and enjoy it on our behalf…and still be a properly threatened family man.” On stage with Tina Brown, Douglas said “it is a quality which I learned in that picture that helps me get away with murder.” He made the confession while seated alongside the king and queen of Toronto’s conservative Jewish contingent, Gerry Schwartz and Heather Reisman. His father’s legacy alone would have secured him a spot at their table, but his three-part attempt at soft core sabotage suggested he preferred to sing for his supper. As he told us, “I love the challenge of seducing an audience.”

His dad doesn’t. Kirk Douglas has been the archetypal tough guy ever since 1949’s Champion. Though father and son look remarkably similar, their approaches are not. In the ’50s and ’60s, the Golden Age of Television, Kirk chose show-stopping roles at a time when films turned into spectacles to attract audiences. As Kirk said in The Films of Kirk Douglas, “I’m not interested in being a ‘modest actor.’” Despite physically evoking his father, Michael professionally refuted Kirk by embracing the very style his dad rejected. Thomson argues that this “has allowed Michael Douglas to play a man who is weak, culpable, morally indolent, compromised, and greedy for illicit sensation, without losing that basic probity or potential for ethical character that we require of a hero.”

As Tom Sanders in Disclosure, Douglas took on his third and last “fall-guy type” role. The type had by then become as much of a reference for nineties erotic thrillers as femme fatales, according to Williams, and was so indistinguishable from Douglas that the film even included a meta-quip — Dennis Miller’s character says to Douglas, upon hearing he has slept with seductress Meredith Johnson, “You’ve seen more ass than a rental car.” The line begged the question: was Miller talking to Douglas or his alter ego? Was there even a difference?

Decades before we gained access to every aspect of celebrities’ personal lives, Douglas suggested his fans could access his personal life by watching his sex thrillers. In 1987 he told The Toronto Star that in the midst of reading the screenplay for Fatal Attraction, he realized he would have to drop the act to play Dan Gallagher. “I sort of froze, put down the script and said to myself, ‘This is me, man. This is just going to have to be me, and there’s something scary about that fact,’” he recalled. “It’s the closest I’ve come to having to play myself — far more than in any film I’ve done.” Though Douglas denied having had an Alex Forrest-type experience, years later he and Kathleen Turner admitted they had an affair on the set of Romancing the Stone. And in 1995 People reported Douglas’ wife Diandra, who divorced him in 2000, said “the other women were difficult to deal with.”

Perhaps this explains the press’ confusion when Douglas entered rehab in 1992. The Sunday Times reported he admitted himself to “get his sex addiction sorted.” The journalist had overheard the news at the bar, but the press ran with the story — it neatly tied in with Douglas’ on screen persona and off screen rep. The fact that Douglas denied being a sex addict almost 15 years later did little to change their minds. “Around 1990, I voluntarily went to rehab because I was drinking too much and some smartass editor of one of the British tabloids said, ‘Oh, another boring story about an actor going to rehab. Let’s give him sex addiction,’” he told Total Film in 2006. “And then it became ‘self-confessed sex addict!’”

Douglas didn’t exactly put those rumors to bed last year when he claimed oral sex was to blame for the tongue cancer with which he had been diagnosed in August 2010. “[T]his particular cancer is caused by HPV, which actually comes about from cunnilingus,” he told The Guardian, adding, “cunnilingus is also the best cure for it.” Then he used the F-word.

I’m not saying that I don’t say “fuck.” I say it a lot. All the time even. But I didn’t expect Dan Gallagher to say it. The F word is reserved for women like Alex Forrest (and me), not him. In Disclosure, Tom Sanders’ wife gives him a withering look when he rants, “Why don’t I be that evil white guy you’re all complaining about? Then I could fuck everybody!” At that dinner, I gave Douglas the same look when he used the F-word like an ice pick to punctuate the end of a stream of celebrity pabulum. “‘The fuck of the century’ took nine days,” he drawled, quoting his character Nick Curran in Basic Instinct. “Nine days. Nine days,” he repeated with mock wistfulness as the audience laughed. Buoyed by their response, he tacked on, “I have a new appreciation for porn.”

This was not Nick Curran, or Tom Sanders, or even Dan Gallagher. This was Michael Douglas. He wasn’t the everyman who used euphemisms for copulation; he was just another crude celebrity. On film, Douglas was a means to an end, but in person he was an end in himself. Like everyone else I now saw him as a sex addict. I missed the time I saw him only as an actor who put the second sex first. It was a rare move in the ’80s and it is a rare move now — these days, male super stars seldom show weakness, more seldom still in the presence of a powerful woman. “I’ve dropped my pants for the last time,” Douglas told Total Film in 2006. Eight years later, at the end of the Tina Brown dinner I looked around for him, but he had already left the building. “I woke up, you weren’t here,” Alex says in Fatal Attraction. “I hate that.” I knew how she felt.

Soraya Roberts is a Toronto-based writer who has contributed to Salon, Slate, The Daily Beast, BuzzFeed and more. She is polishing her first book and thinks you should read it one day. She likes to be followed @sorayaroberts.