The Best Time I Was a Teenage Ayn Rand Worshipper

by Isabel Slone

We all make mistakes. It’s a platitude offered by well-meaning adults when they need a limp defense for an inexcusable action; like Britney Spears’ 55-hour marriage to her high school sweetheart, or pretty much anything that’s ever appeared on Amanda Bynes’ Twitter. But I believe in forgiveness above all else, because I harbor an equally disturbing secret: I was a teenage Ayn Rand worshipper.

As a teen, I had what we’ll call “problems.” By the time I entered high school, I had experienced an umpteen amount of social rejection (we’ll call that The Best Time My Former Best Friend Wrote Me A Note Saying Nobody Liked Me Which Was Signed By Every Single Girl in Grade 6) and decided that self-imposed social exile was the best option. I preemptively hated everyone so it wouldn’t matter how they felt about me.

Once puberty kicked off, my “problems” morphed from the occasional outburst to a scary, constant, roiling anger that affected everything I said and did for the better part of four years, like being drunk on a combination cocktail of hostility, rage and isolation.

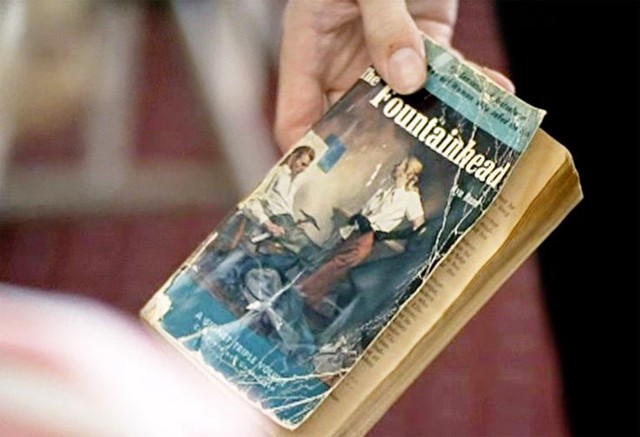

Whether I was looking for it or not, I found a great conduit for my negativity: The Fountainhead. I learned of the book through the other classic read for millennial social outcasts, The Perks of Being a Wallflower, and became enamored with its flowery, descriptive prose. I thought it was the most well-written book I had ever read. It was also the thickest book I’d ever seen; just carrying it gave me a smug sense of superiority. Little did I know I had just discovered The Book that transforms lonely teenagers into dead-eyed conservative minions.

The Fountainhead’s plot is centered on Howard Roark, a flame-haired architect who designs buildings that look like “a cross between a filling station and a comic-strip idea of a rocket ship to the moon.” His unconventional designs don’t get him many commissions, and he has great difficulties relating to other people. Howard Roark’s response to anything is to emit a cold, condescending laugh. He insults people straight to their face and is surprised when they are offended. His peers are generally creeped out by his cold, piercing stare and single-minded obsession with brutalist buildings. But his lack of social skills are never characterized as a problem; he’s uncompromising, not a sociopath.

In the book, human reactions are twisted like funhouse mirrors. When Roark falls in love with the emotionally-withholding ice queen Dominique Francon, he barges into her house and brutally rapes her. Ayn Rand doesn’t deny it is rape, but somehow characterizes it as an expression of mutual care; “had she meant less to him, he would not have taken her as he did; had he meant less to her she would not have fought so desperately.” This perpetrates a scary message completely antithetical to “no means no.” And this isn’t even the end of Roark’s extreme behaviour. He dynamites a building he designed after discovering small changes were made to the original plan.

In her series Truisms, conceptual artist Jenny Holzer writes, “Alienation produces eccentrics or revolutionaries.” The Fountainhead magically convinces eccentrics that they are revolutionaries. After one read, suddenly it was okay that my life was completely devoid of human connection. Howard Roark didn’t need people, so neither did I. I no longer saw myself as a social reject. I was actually an unrecognized genius! Everyone else was just too stupid to understand. Ayn Rand excused my social ineptitude and put it on a pedestal.

I may have gained self-confidence from reading the book, but I also ended up with an insufferable superiority complex that ensured I did not get laid for a very long time.

The weirdest thing about being a teenage Ayn Rand worshipper is that I didn’t even consider myself to be particularly right-wing. The Fountainhead (and even more so, Atlas Shrugged) is a stolidly capitalist allegory for individual interests trumping the needs of the poor and downtrodden. It’s been publicly embraced by Republicans like Alan Greenspan and Rand Paul, who once referred to social security as a “Ponzi scheme.”

I, on the other hand, supported gay marriage, went to climate change protests, and owned a copy of the NOFX album The War on Errorism featuring a cartoon of George W. Bush in clown makeup. But overwhelming loneliness made me vulnerable. Now reading The Fountainhead is like pouring a bottle of cherry cough syrup in my eyes — cloying and painful. I’m completely embarrassed that I spent a good four years toting that book around as an example of my own superiority, refusing to drink or have any sort of fun because I didn’t want to be lumped in together with my “second-hander” classmates.

I can’t exactly pinpoint the moment when I realized that Ayn Rand was a fascist; people just grow up and out of things. After my brief fling with The Fountainhead, my anger took on a more distinctly feminist flavour. I discovered riot grrrl culture, and the antagonizing wails of Bikini Kill externalized how I felt. I also miraculously managed to find a boyfriend, and learning to care about another person for the first time was crucial to leading me out of that Objectivist tunnel.

I’m happy to say that I no longer see the virtue of selfishness, but my once-beloved copy of The Fountainhead still sits on my childhood bookshelf, reminding me that, once upon a time, I was a real asshole.

Isabel Slone is a Toronto-based writer and ex-fashion blogger. Her work has appeared in the Globe and Mail, Hazlitt, WORN Fashion Journal and more.