Disrupters, Disconnectionists, and Dicks

by Emma Healey

On Tuesday, Nev Schulman took a selfie in an elevator. The photo shows him standing with his hand over his heart, staring all serious straight into his iPhone. In the corner, a bag of groceries and a water bottle rest against the door to block it from closing. The light in a closed elevator is rarely flattering; when you have upwards of 740K followers, there’s not much room to fuck around.

“Cowards make me sick,” read his accompanying tweet. “Real men show strength through patience & honor. This elevator is abuse free. #RESPECT.”

Nev Schulman is the star of the 2010 documentary Catfish, a film about the time he fell in love with an impostor on Facebook, as well as the host of MTV’s Catfish: The T.V. Show, where he counsels people who fall in love with impostors on Facebook. The tweet was ostensibly inspired by his outrage over the recently leaked video of Ray Rice hitting his fiancée in a (different) elevator.

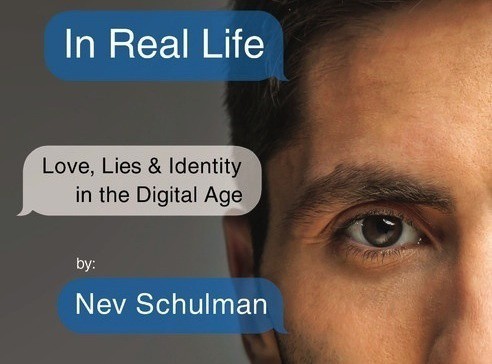

At first it was a joke. But then there was the question of his recently released memoir, In Real Life, where Nev talks about how he was expelled from Sarah Lawrence in 2006, a school his “active alumna” mother had to “beg” to get him into because of his history of bad behavior.

Sarah Lawrence’s former Assistant Dean of Student Affairs, Ken Schneck, recently said that Nev “was a condescending, entitled, reprehensible tool” during his time there. This statement seems accurate: in his book, Nev says that as a student he sold drugs, threw “massive” parties, slashed a guy’s tires, and “took a dump in the cereal dispenser” in the school’s cafeteria.

In the memoir, Nev says he was photographing a campus event when someone tried to grab his camera. Believing his assailant to be male (since they were “stocky” and had “crew-cut-styled” hair), he lashed out in self-defense and punched them in the face before realizing they were female. The school subsequently expelled him. According to him, the whole event was a regrettable misunderstanding.

However, other sources described the incident differently. People who were at the party say Nev was taking pictures without permission; he tried to photograph two women kissing, and when one of them tried to stop him, he punched her.

If you saw the Internet backlash but had never watched an episode of Catfish before, you were probably just like, ugh, who the fuck is this guy? But for those of us who are familiar with the show, none of it was all that surprising.

My whole thing about Catfish is, at this point, a matter of public record. To me, it’s always felt less like a standard-issue reality show than a fascinating series of awkwardly produced short films about the different shapes human loneliness can take. Some people originally read Nev’s elevator tweet as a tasteless joke, but the truth is actually way harsher. That photo is a perfect distillation of Nev’s public persona: a smooth, full-bodied blend of condescension, unearned confidence, and misguided self-righteousness which so pervades the fabric of the entire Catfish franchise that the phrase “douche chill” was, I think, invented solely to describe the experience of watching this man comfort lovelorn victims of internet fraud.

At best, Nev’s general steez feels disingenuous; at worst, his attitude reminds me of some of the most dangerous men I’ve encountered — the kind who are capable both of assaulting women and of speaking out publicly against misogyny and abuse without ever recognizing any kind of disconnect in their behavior.

So that’s Nev. But what about Nev’s book?

Before we go any further, I want to make something absolutely clear. In Real Life: Love, Lies & Identity In The Digital Age is not a good book and I don’t think you should read it. But I’m glad I read it — and not just because it affirmed my long-held suspicions that the author is a clued-out dick.

These days, the idea of ditching your smartphone in order to lead a better life is one of the hottest topics for editorializers and self-helpists; whether you’re a standup comedian, a different standup comedian, a million bloggers, a hard-to-watch spoken word artist or just an average everyday CEO, if you’re over the age of 20 and have even a passing interest in giving prescriptive advice, you’ve probably already written a manifesto about how our collective cultural addiction to the Internet and social media is stunting our emotional growth.

There are a lot of things about The Way We Internet Now that are truly unsettling. As a depressive with a smartphone and a job that requires me to be online for at least eight hours a day, I’m familiar with the particular, echoing isolation that comes from overexposing myself to the c a s c a d e almost daily. Nobody has been forcing me to read all these tech-detox stories. I know what I’m doing when I open up another essay about the importance of throwing your modem out a window is not (just) hate-reading; I am always hoping for new insight into how, exactly, this nonstop barrage of information is affecting my mind, because in my heart of hearts I am afraid that it is doing something bad, something irrevocable.

I think this is why appeals to disconnect and unplug will always find an audience no matter how slapdash or rote they might be. It is frightening to think that you might be a willing partner in the steady proliferation of your own sadness just because you’re checking Facebook all the time. It’s unsettling to remember that corporations can permanently alter the definitions of words like “friend” and “favorite” in the blink of an eye, or to consider that the concept of “connection” is just as mutable. It is scary to be told that the world is changing for the worse and that you’re a part of it. It is scary to look inside yourself and find that maybe you agree. Reading essays that tell me to get off social media is a way to confront my own insecurities, to question my own motivations for staying.

But I also don’t think anyone is helped by easy platitudes about how putting down your Instagram-box and picking up a windsurfing board will remind you to look into the eyes of a child and appreciate the wonders of life. What I’m waiting for is a writer who understands the complexities and nuances of trying to be a person both on and in spite of the internet; for the kind of writing that gives its readers the expansive, resonant relief of understanding and being understood, of being chastised, forgiven, and encouraged to do better all at once.

I did not find any of this in Nev Schulman’s memoir. What I did find was a repetitive call to get off social media in order to improve — nay, save — myself. The book somehow manages to feel both tired and frantic, full of predictable advice delivered in a weird, narc-y register and peppered with subtly disturbing stories from Nev’s own personal life.

All of it builds to the same conclusion that countless other lazy, opportunistic Hot Takers have been coming to for years now: if you want to live a full life, you’ve got to stop tweeting and go outside sometimes (it seems mean at this juncture to point out that if someone had simply given this man a copy of his own book earlier this week, he might’ve avoided a PR fiasco, so — I won’t).

Tone-wise, this book is the literary equivalent of a clean-cut guy in a leather jacket sauntering into your classroom, turning a chair around so he can sit on it the cool way, and telling you he wants to have a serious rap sesh about the problems we all face, because he’s been there, man. In terms of genre, it’s either a memoir by someone who hasn’t had a particularly engaging life, or a self-help book by someone who has no idea what he’s talking about.

Either way, it’s unclear who exactly this book was written for besides Mr. Schulman himself — but he still wrote it and I still read it, so in the end I guess it’s hard to say which of us is the bigger chump.

IRL has three main narrative modes. There’s the memoir, where Nev talks about his youthful misdeeds, his rise to stardom via Catfish, and his current relationship. There are his observations, where he discusses the different kinds of catfish he’s met. And then there’s his advice.

The observations are the smallest and least objectionable part of IRL, and to be honest, if this whole thing read like Chapter 2 (“What Is A Catfish?”) I’d be 100% down. Its awkward production and flawed hosts notwithstanding, Catfish is a fascinating and complicated show. Every episode is shot through with broader issues of race, class, and mental health which are rarely (if ever) directly addressed on-camera, and when I first saw that this book existed, I felt a faint hope that it would explore what actually makes the show engaging and tragic and different. That hope, as you’ve probably guessed, did not pan out.

Instead, Nev wants to cement his place in contemporary culture as a Leader of Men. His own experience of being catfished has led him to realize that “my calling — my niche, my purpose — was to serve as some sort of mediator. I could be a leader of the vital conversations about how life and relationships are changing now that we spend so much time online [… and] what I could bring to this discussion… was empathy. I’d been there.” As someone who has spent some time in the trenches of social media, he knows that “only once we step away from the Internet and start living in real life will we be able to find what we really want: love, connection and self-fulfillment.”

Per Mr. Schulman, the path to this emotionally connected Real Life should be paved with relentless attempts at self-improvement — joining a gym, finding a therapist, “think[ing] of yourself as a car” in need of a good mechanic and acting accordingly. None of these things are bad ideas, exactly. It’s probably true that a lot of us would be happier if we started working out more or seeing a therapist. But in this book, as on the show, this frantic insistence on SETTING GOALS AND REACHING THEM TO BECOME YOUR BEST SELF feels desperate, inadequate, and achingly hollow.

The worst parts of the book, however, are the ones where Nev gets into his personal life. Onlookers who’ve read about the Sarah Lawrence incident will already have seen the bizarre tone he assumes when addressing his past and his flaws. Whether he’s talking about getting kicked out of school, “breaking [his] best friend’s face” or, more recently, getting so mad over a petty dispute during Catfish filming that he throws his iPhone hard enough to shatter its screen, Nev-as-Narrator manages to pull off the impressive feat of constantly gesturing towards regret while conveying absolutely nothing.

This technique is creepiest when he tries to plug his personal experiences into his broader thesis, and Chapter 18, entitled “You/Me/Us,” is where shit really went off the rails for me.

The story goes like this: decades ago, in 2012, Nev used to sleep around. He cheated on girlfriends, flirted recklessly (“to the point where women would often feel uncomfortable”), used Facebook to maintain a “little black book” of “cute girls” to chat with, and bolstered his sense of self-worth with a ton of one-night stands.

But after a particularly gross night in Palm Beach, he resolved to change his ways and took a vow of celibacy. “It was about changing my behavior so that I was no longer interacting with women on a sexual level only. Instead, I would talk to them, listen to them, have (gasp!) meaningful conversations,” etc.

To his surprise, abstaining from sex made him feel good; women were less skeeved out by him, and he actually felt more powerful now that he wasn’t trying to bone down 24/7. “It was the difference between the way a lion hunts to catch and devour its prey and the way a squirrel collects and stores nuts for winter,” he says of his newfound attitude. “I understood that I was investing in a longer-term, more sustainable satisfaction rather than a quick rush.” During this period, he got serious with the woman who became his long-term girlfriend, and through her he learned that true love means being vulnerable and open, not closed-off and shallow.

This process, Nev asserts, is similar to deleting your Facebook account. He drops this comparison casually, in the midst of a bunch of other platitudes about vulnerability and emotional connection, as though it’s completely reasonable to equate the act of reining in your sexual activity with the act of deactivating a profile. As his period of celibacy wore on, Nev says, “I deleted my ‘Cute Girl’ group on Facebook”; shortly after that, he ditched Facebook altogether. Not having sex all the time helped him to reach a new level of enlightenment that made both Cute Girls and social media unnecessary, and cutting the shallow things out of his life — whether they were fellow human beings or pictures of himself on a screen — pushed him toward real connections, the deeper, more involved kinds of relationships that actually matter.

The logic of this little parable looks shiny and smooth on the surface. I’m sure it makes perfect sense to him. But I don’t really need to tell you what’s so immensely fucked up about all these “revelations.” I don’t need to point out that his lion-vs.-squirrel metaphor posits women as either prey or resources, and that thinking of them as the latter isn’t really an improvement over the former. Nor do I need to say that the possibility of a woman wanting or needing sex on her own terms doesn’t seem to have ever occurred to him. I don’t even need to ask what it says about your conceptions of self and sex and masculinity and the big bad world that exists outside your own skull if you truly believe that the best possible way to be respectful of women is just to stop trying to fuck every single one you meet, and the best way to be sensitive to potential romantic partners is to unilaterally decide that your dick won’t touch them until you’ve decided your connection is sufficiently “real.” I don’t need to explain that in this story there is no actual change in the narrator’s perspective, only in his surface-level behavior, because it’s obvious. Or it should be.

The most concise encapsulation of this stunning wrongheadedness is in the midst of this chapter, in a parenthetical that appears while Nev’s describing the myriad benefits of his experiment with abstinence. “Being the guy who didn’t hit on [women] just made me more interesting,” he says. “(Bonus! More women interested in me! Too bad I couldn’t take them up on it.)”

Too bad, indeed. What he doesn’t seem to understand is that whether he’s actively flirting and fucking or not doesn’t actually matter at all — either way, the only person he’s paying attention to is himself.

This kind of self-involvement is particularly insidious because it disguises itself as interest in the well-being of other people. It’s also, in some way or another, at the core of most of the essays and videos and arguments that urge us to put down our phones.

It’s true that some aspects of social media do encourage us to play our real-life relationships like a never-ending low-stakes video game. We should absolutely endeavor to remain aware of that — and of all the ways we choose to distribute our time and attention, because some of the most crucial experiences and ideas we have come when we find ourselves fully immersed in something or someone else that drags us out of our own heads.

But that’s the key — we have to go outside ourselves. Disconnecting from the internet might help us reclaim some small lease on our attention, but that attention does us no good if we’re just feeding it back into ourselves on an endless loop. Putting down your phone doesn’t equal putting real work into empathy, just as not actively pursuing sex doesn’t equal granting women the status of complete human beings in your mind. Fetishizing “presence” by telling everyone to stop staring at their phones perpetuates the myth that simply being around other people automatically means you’re attuned or empathetic to them. As if it’s impossible to have a real, face-to-face conversation with someone and still fail to take in a single word they’re saying. As if it’s impossible to spend hours staring at Facebook and still be a good friend to your real friends later.

Confusing the easy work of “unplugging” with the hard work of meeting your feelings of solipsism and alienation and distraction on their own turf doesn’t benefit anyone. Ultimately, the doctrine of disconnection-as-self-improvement can only offer us the same kind of shallow distraction that social media does. The Internet isn’t just a diversion from real life — the Internet is real life, and the people saying otherwise are simply exploiting our insecurities for clicks, views, attention, and profit. The real work of “connecting” is still just in learning to live with ourselves, and others, and our faults, and not stop caring. Nev Schulman is not the man he wants us to think he is, and there’s no tweet in the world that can convince us otherwise.

Emma Healey once wrote a book of poetry called Begin With the End in Mind, but now she only thinks, reads and writes about Catfish. And occasionally Dating Naked. Talk to her about Dating Naked here.